What becomes of a damaged and destructive man after he works to fix himself? What becomes of his art? His relationships? His life? Abel Ferrara’s “Tommaso” explores those questions and others with blunt honesty, never pretending it has the answers.

I love this movie. Adore it. Can’t stop talking about it to my friends. I am aware of its problematic aspects. In subject matter and style, it is (intentionally) a bit of a relic, certainly in terms of focusing on a toxic man, or a man who was once toxic. And there are other, related issues that I’ll deal with in due course. But the film depicts a subtle, complicated, mostly internal process so thoughtfully—blending humility and go-for-broke nerve—that its flaws seem minor.

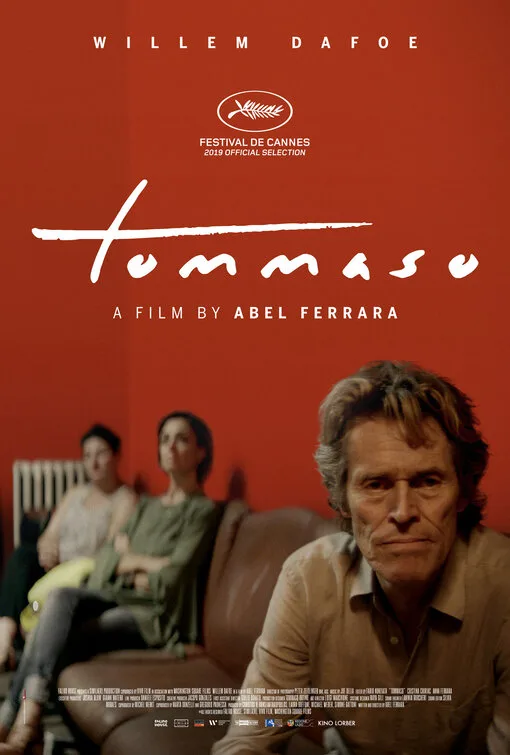

The film stars Willem Dafoe as an actor and filmmaker. Like Ferrara in real life, Tommaso is a recovering drug addict and alcoholic living in Rome with his much younger wife and toddler-age daughter. We watch as he works on an unproduced science fiction movie about a man surviving in a wasteland and learning to love again. We observe as he does little things that give him joy, such as walking into a local coffee shop, ordering one small beverage, gulping it down and walking out. We see him attend an AA meeting and talk about his past life and his struggle to stay clean. We watch him apologize to his wife Nikki (Cristina Chiriac) for not being as attentive to her and their daughter Dee Dee (Anna Ferrara) as he should be, and discuss how the child they treasure has come between them as a couple. Their subsequent sex scene is interrupted by that same child calling for mom. Life-sized stuff, all of it.

But there’s trouble brewing. Tommaso sees Nikki in the park with another man and becomes obsessed with her infidelity, alternately blaming himself, her, the man, and other factors. The hero’s beatific calm crumbles and the film becomes more chaotic and volatile. The filmmaking anchors us to Dafoe’s expressive face as he’s looking at things, or imagining things. The point-of-view is so subjective—Tommaso’s at the center of every scene—that it’s often hard to tell how much of the hero’s anxiety, paranoia, and anger are sparked by real things and how much is the result of letting insecurity get the better of him.

This is all meticulously conceived and executed, despite the directness of the staging and camerawork and the outward impression that the actors are winging it. Even the fantastic or expressionistic or otherwise not-quite-objective storytelling elements are of a piece with the plainer elements. And after a certain point you have to quit worrying about what’s “really happening” and what isn’t, and accept all of it as a method of illustrating what’s happening inside Tommaso.

There is also a religious dimension that draws on Ferrara’s rich history as a macho Italian Catholic New York filmmaker, telling violent, provocative tales of men and women on the edge, chock full of sin, sex, drugs, drinking, and graphic violence. In a lot of ways this movie feels like an answer to, or kindhearted kid brother of, Ferrara’s “Bad Lieutenant,” also about a troubled man, though a more self-destructive and brutal and sometimes evil one. You can see a similar relationship between Scorsese’s two films about insomniac New Yorkers in vehicles: “Taxi Driver,” about a lonely cabbie who wants to kill, and “Bringing Out the Dead,” about a loving EMT who wants to heal. Ferrara’s talking across time, speaking to himself and his filmography, which contains many alcoholic or drug addicted characters and often deals with substance abuse through metaphor (as in “The Addiction,” a low-budget drama about vampires).

Of course there’s a metric ton of Christ imagery, as in so many of Ferrara’s movies. Ferrara is deploying religious iconography to connect Tommaso’s lived experience to the moral framework he learned as a child. The hero is often filmed in crucifixion poses. There’s a scene that plays like a cut moment from Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ,” but in post-millennial street clothes. Sometimes we feel that Tommaso is dramatizing his torment in lieu of constructively engaging with it: a narcissist nailing himself to cross instead of dealing with what’s in front of him. But we also see Tommaso behaving in accordance with Christ’s teachings, replacing anger with compassion, de-escalating situations that could spiral out of control.

It helps in this kind of movie to have Willem Dafoe play the hero. Not only has he portrayed one of the great cinematic Jesuses (in Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ”), he’s played Christ-like figures (notably in “Platoon”) and secular spiritual pilgrims. He’s also played villains, monsters, abusers, and tempters, always with conviction, sometimes with relish. He channels the dark and light sides here, making us love, pity, and root for the character, then loathe him (as Nikki sometimes does). This is one of the great Dafoe performances—a summation of everything he’s done and everything he’s about.

Tommaso was a womanizer during his drug days, so we aren’t surprised when he starts to stray, or tries to, out of pride, or fear of relative impotence (he feels old next to his young wife, and being cuckolded amplifies that a thousandfold). We also watch the suppressed anger start to build within him, to the point where his movements become wilder and more impulsive, and his conversations with Nikki more insinuating, combative, and petty.

As the film unfolds, there are sex scenes, sex fantasies, make-out scenes, and chaste flirtations with younger women (including a student and a fellow AA group member). Some of these are “real” and others are clearly fantasies, and clunky ones at that, settling into a mode reminiscent of the Great Director-driven, very male European art house pictures lauded in the ‘60s and ‘70s. These tendencies are leavened by Ferrara’s attention to psychology. We learn that Nikki might’ve been drawn to Tommaso because her own dad abandoned her at a young age, and there are suggestions that, like the older professor in “Moonstruck” who keeps hitting on female grad students, Tommaso fixates on younger women because he fears death. A student that Tommaso flirts with tells him a story about her father that sounds like it could’ve happened to Nikki. Sexual and romantic patterns repeat themselves in people’s lives, just like cycles of addiction and recovery. Attraction itself is an intoxicant. That’s why people describe being in love or lust as a “rush.” They get high from it.

As a writer/director, Ferrara does what we see Tommaso do in a fantasy: he tears his own heart from his chest and asks his audience to pass it around and take a good look at it. Ferrara shot the movie in his adopted city, Rome, where he settled after relocating from his hometown of New York, a place he now avoids because he associates it with past drug and alcohol abuse. The principal location, Tommaso’s apartment, is Ferrara’s apartment. Chiriac is Ferrara’s wife in real life, and Anna Ferrara is their daughter. Many of the supporting characters in the film could be Ferrara’s friends. I’m guessing about that last part. I don’t know their backstories. But I do know that I’ve never seen most of them before, and their performances have a directness and and simplicity that reminded me of the tradition of Italian Neorealism, which cast nonprofessionals as versions of themselves.

Dafoe brings himself to the project as well—so much that it turns the character into a hybrid of Dafoe and Ferrara. We see Tommaso teach an acting class that includes rituals, dance routines, and role-playing exercises that could have been drawn from Dafoe’s experiences as a drama teacher, or a young actor in training. We also see him meditate and do yoga exercises in long scenes that confirm that Dafoe is strong and graceful for a man in his sixties. Ferrara often shoots these moments full-frame, Dafoe nearly naked, the better to appreciate how well he’s taken care of himself.

“Tommaso” doesn’t play by the rules of most recovery dramas. You don’t follow Tommaso through the usual arc of using, bottoming out, recovering, and making amends. When the film starts, the character is already in recovery. We learn about his past life through his stories. It’s a slow film, on purpose: this man used to rush through life, never paying attention to what’s around him, and now he’s savoring everything because he knows he’s lucky to be alive. We sense his fuller appreciation of life even in throwaway moments, as when cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger’s camera follows him through his apartment, passes him as he stands at a doorway overlooking a terrace, drifts outside and tilts up, taking in the full height of an apartment complex across the way, then settles on the sky and takes a nice, long look at it. A touch of Terrence Malick.

An AA buddy coaches Tommaso on his journey by telling him that anger takes up interior space that could be used for positive emotions. Anger is also an addiction, and because you can never really defeat or expel it, only recover from it and manage it, you have to intentionally send good energy out into the world, to contrive reasons to experience the opposite of rage. That means seeking out or inventing situations that will permit the open expression of love and kindness. The AA buddy tells Tommaso that these positive feelings and experiences—generating demonstrating and accepting love—go inside you, and occupy space ordinarily claimed by anger. That’s one of the greatest pieces of advice I’ve ever heard in a film. It inspired me to try it, and I am here to tell you that it works. Who could have expected Ferrara to make a film that could teach people how to manage anger? I didn’t. I bet he didn’t, either. But here we are.

I will return to Tommaso many times. It has lessons to teach. The teacher knows what he’s talking about because he’s been there, and still is there. And he’s so good at making you think that you never feel as if you’re in a classroom. This isn’t Sunday school in film form. This is Jesus going out among the people, talking to farmers and shopkeepers, bartenders and sex workers, fishermen and thieves, in plain language, as described in the Book of Corinthians. Ferrara’s practicing the Gospel of the street. You’re not supposed to figure it out like a puzzle. You’re supposed to listen to the story, then try to figure yourself out—knowing that, like Tommaso, you always were, and will always be, a work in progress.

If this film were a person, I would risk my life to save it.