“To Kill a Priest” is a movie of great, almost crushing, sincerity, but it is so ineptly made that scene after scene strikes the wrong note, or no note at all. Set in Poland in 1981, at the dawn of the Solidarity movement, it tells the story of a radical priest and the security agent who shadows him for months and finally kills him. This dramatic material generates such a small emotional response that I was puzzled; surely a story like this should try to really work us over.

But “To Kill a Priest” is never able to organize and aim its emotions.

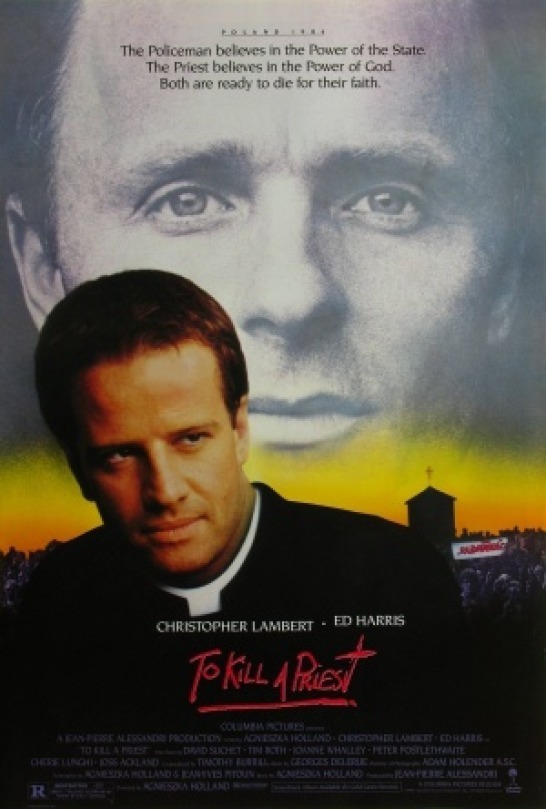

One of the problems is in the way the movie presents the two most important characters. The priest, a handsome young man played by Christopher Lambert, stands in the pulpit and recites Solidarity sermons of crushing banality. In his private life, he is so solemn and stolid we find it difficult to care about him, and things aren’t helped by the addition of a gratuitous subplot in which he is attracted to a young woman but successfully resists temptation. Has there been a young priest in any movie in the last 20 years who was not distracted by carnal desire? The security agent is played by Ed Harris, an incomparably more interesting actor who does know how to deliver an impassioned speech (his defense of murder is more convincing than any of Lambert’s sermons). In fact, the single change that would have helped this movie the most would have been to switch the roles played by Lambert and Harris. That would have given us a hero we could care about and a villain whose blank features and listless personality might have seemed part of the role. The movie’s lack of originality is reflected in the assumption that the hero must look “heroic” and the villain more ordinary. That kind of typecasting is so obsolete it’s almost distracting.

Even though Harris is capable in the role of the security man, the role is written so confusingly that we can never be sure of our feelings for him. Much is made of his homelife, of his wife and solemn-faced son, and yet if you think back over all of the domestic scenes, each one of them seems desperately written to illustrate traits that the others contradict.

They lead up to one of the movie’s several unintentional laughs, when the agent, weary after a night of violence, falls roughly on his wife for sex, after which she says, “And I thought you didn’t love me!” One of the side effects of the contrast between Harris and Lambert is that I actually felt more identification with the killer than his victim – hardly the effect the film must have intended.

The central characters are surrounded by many others, too many others, in an international cast. The movie might have seemed more convincing if it had been made in Polish and subtitled in English, but instead we get a bewildering array of accents. Lambert sounds vaguely French, Harris is American and his son is so British he sounds like a parody (“Please, father, may I have a dog?”). Couldn’t they find an American kid for the role? No one sounds Polish in the movie except when they sing the Solidarity hymn, which is in Polish (but not subtitled, of course).

The plot involves the priest’s growing influence over his followers, and the mounting alarm of the security apparatus, led by Joss Ackland in a fine, gravel-voiced performance. Ackland seems to be telling Harris to murder the priest, although the point remains unclear, and Harris does indeed murder him, after great difficulties and comical ineptitude. (By mentioning the murder, I hope I am not revealing any secrets about a movie that destroys any possible suspense with its title.) In the hands of a Bunuel or a Hitchcock, the murder sequence might have generated some power. Everything goes wrong as Harris and his two goofy colleagues kidnap the priest and bludgeon him to death.

They’re even stopped by local cops. And they allow a key witness to escape, leading to a final series of scenes in which justice is done, at great and boring length. Agnieszka Holland, who directed and co-wrote this film, should have studied Costa-Gavras’ “Z” and Pontecorvo’s “The Battle of Algiers” for the way in which they dispatched the villains with great emotional effectiveness at the end; her conclusion drags on until the audience is winding its watches.