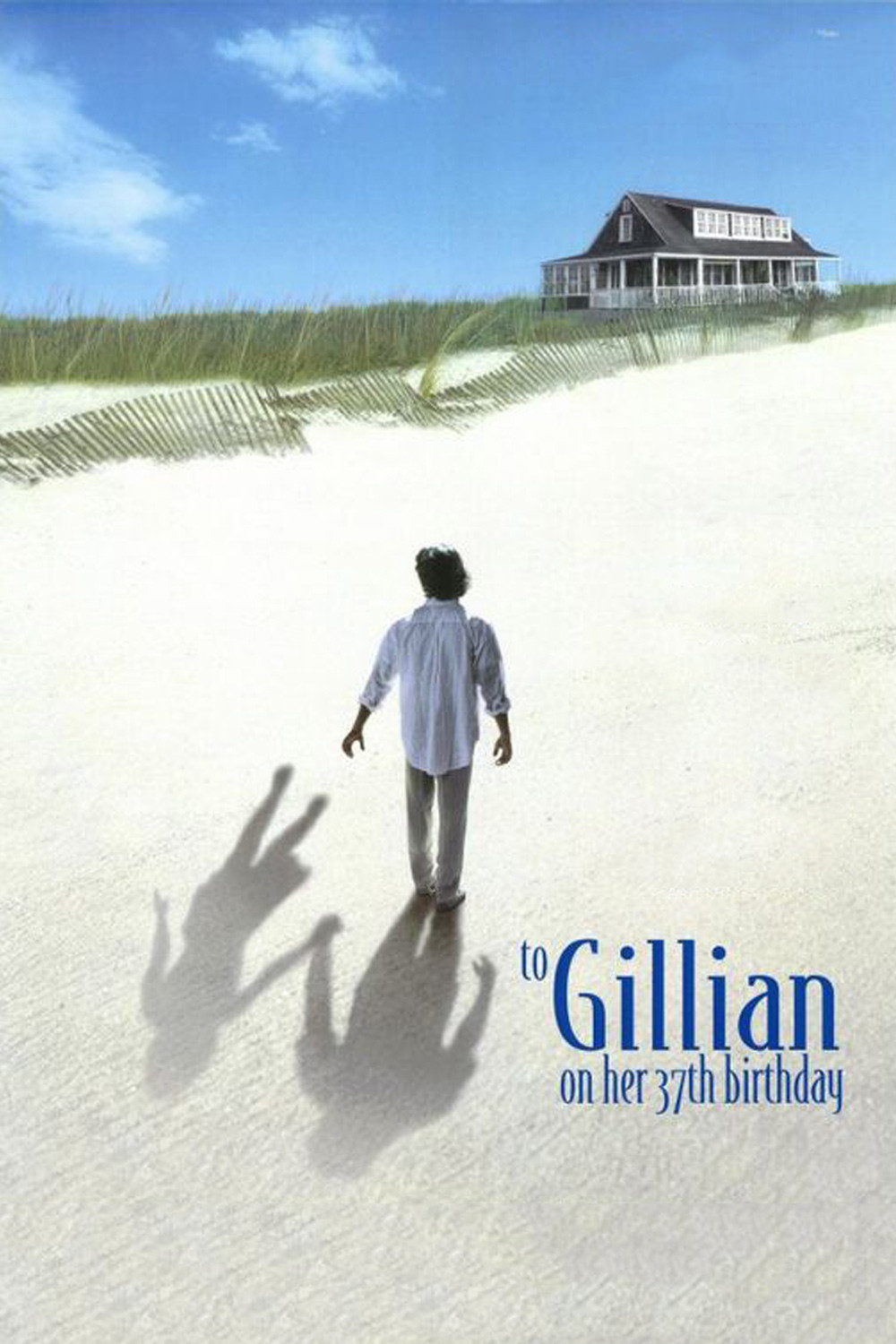

“To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday” is one of those movies in which nosy but well-meaning relatives try to force a reluctant family member to embrace a truth that is obvious to everyone except him. In this case, the truth is that we cannot allow ourselves to be paralyzed forever by grief over the death of a loved one. Why do I always root for the recalcitrant family member? The movie takes place two years to the day after Gillian (Michelle Pfeiffer) fell from the mast of a sailboat and died. It is also her birthday. Her husband, David (Peter Gallagher), since then has lived as a recluse on Nantucket Island with his 16-year-old daughter Rachel (Claire Danes). She suspects that he fantasizes his wife is still alive, and goes for long walks and talks on the beach with her. Rachel is correct.

To observe “Gillian’s Day,” as it is known in the family, Gillian’s sister Esther (Kathy Baker) and her husband, Paul Bruce Altman), arrive with a female friend named Kevin (Wendy Crewson). She is intended as a blind date, although when she finds out it is Gillian’s Day, she wants to return immediately to the mainland–and so she should, since she plays such an unnecessary role in the drama to follow.

The movie, written by David E. Kelley and directed by Michael Pressman, is well-versed in the cinematic symptoms of excessive grief. David drives too fast, gets in fights with other motorists, plays the radio too loud and goes off a lot by himself. Esther believes it’s time for him to get a grip on himself. Worse, she plans to sue for custody of Rachel, whom she fears is having an inadequate adolescence because of having to spend the offseason on Nantucket.

The movie cannot see that Esther is a deranged nuisance who should mind her own business, that David is entitled to his grief, that Rachel is happy living on the island, and that if Gillian appears to David, so much the better. (She also appears to us, and since we can see and hear her I guess she is “really” there, which gives David an excellent reason for not wanting to leave).

The movie lurches to its sentimental conclusion via several dead-end plot ideas that are introduced but not developed. During the course of the long day and night, Rachel goes out on her first date, with a kid she meets on the beach who has rings piercing his nose, ears and who knows what all, and dyes the sides of his head blond, which is proof in any court of law that he is cool or, if not cool, definitely a teenager. David doesn’t like the kid but allows the date, during which Rachel gets drunk, comes home, barfs, goes to bed, has a nightmare, and then has a heartfelt talk with her aunt and her dad. The subplot (including the dance they go to) is all filler.

So is Kevin, the blind date, who sees she is not needed, says she is not needed, acts as if she is not needed and is not needed. I was also underwhelmed by a side plot having to do with the marital history of Paul and Esther, since this, too, has no bearing on David’s problem.

And what of David? How does he spend his time as a recluse? Well, he’s a literature professor, and claims he’s using his free time to write a book. This sounds like a splendid idea, but not to Esther, who believes he should return to the mainland and go back to his old job. With people like this, how many books would ever get written? We have a national compulsion to insist that people deny their grief. A friend loses a loved one, and three weeks later we’re asking, “Are you OK?” And we want them to say, “Why, yes, I’m doing just fine,” so we can nod in approval. If we were really friends, we’d say, “I imagine you still feel miserable,” so they could say, “Sometimes it’s worse than ever.” As to whether David is able to bid goodbye to his ghost on the beach and return to the mainland, or whether Esther succeeds in tearing his daughter from his side, I will leave you to guess. Here’s fair warning: A movie that hasn’t had an original idea in 83 minutes is unlikely to develop one in the last 10.