“Things Change” is a neat little exercise in wit and deception, in which an old Italian-American shoeshine man convinces the crime syndicate boss of Lake Tahoe that he is the man behind the man behind the man. His secret is to have no secret. He answers every question truthfully. He does most of his talking about how to get a perfect shoeshine. By the end of the film, we have witnessed a con so perfect that the people pulling it didn’t even want to pull a con.

The movie was directed by David Mamet, who wrote it with Shel Silverstein. Coming after the diabolical trickery of “House of Games” (1987), it confirms Mamet” gift for leading us through truly bewildering plots. What makes his movies so entertaining is that the characters are bewildered – not the audience, which is usually the case with sloppier screenwriters. He makes us co-conspirators.

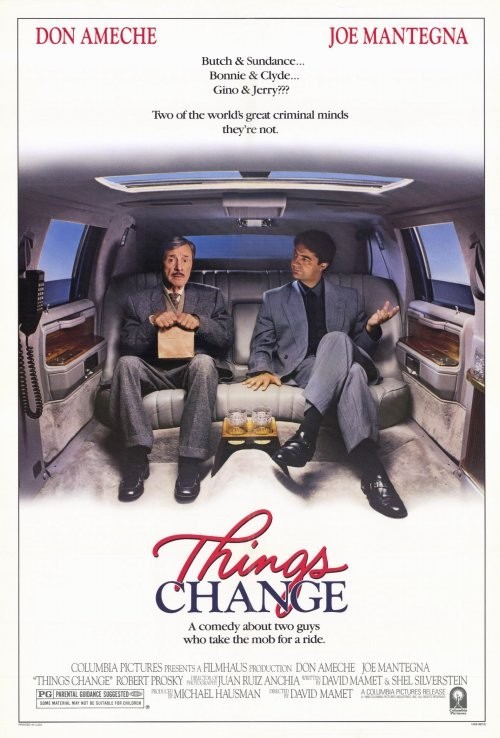

His story is based on a series of accidents, coincidences and misunderstandings. It begins when Gino, the old Chicago shoeshine man (Don Ameche), is escorted from his shop and taken into the presence of a local crime chief (Mike Nussbaum) and asked to confess to a murder.

If Gino agrees, he will be back on the street in three years, and the mob will give him his dream – a fishing boat of his own in Sicily.

First he refuses. Then he changes his mind. The dialogue in this scene is pure Mamet, the repetition of ordinary phrases that take on sinister meanings. Describing the murder of a man in the street, a mobster punctuates each paragraph with the line “This is public knowledge” before finally coming to his point: “What I am now about to tell you is not public knowledge.” When I write it down, it doesn’t sound funny. When you hear it, you laugh. It is Mamet” gift to know how words work aloud.

Gino is assigned to Jerry, a younger syndicate underling (Joe Mantegna), whose job is to guard him over the weekend until he can confess on Monday. The two men retire to a hotel room, where Jerry grows restless, says the hell with it, and decides to take the old guy to Tahoe for the weekend. In Nevada, Jerry is spotted by a chauffeur as a guy from the Chicago mob, and Gino is immediately assumed to be very important. No one has ever seen him before – but that” just proof of how important he is. Of course they get the suite with the sunken tub, free of charge, plus unlimited credit in the casino. Mamet and Silverstein now unspin a labyrinthine plot, in which half-truths and assumptions follow one after another until Gino is in the presence of the Lake Tahoe organized crime boss (Robert Prosky). The don has invited Gino and Jerry to his mountain estate for two reasons: to embrace them if they are the real thing, and to kill them if they are not. In a scene involving exquisite timing and painfully drawn-out silences, the boss tries to get answers without seeming to ask questions, and Gino tries to answer without saying anything. There is not a word or a glance or a moment of body language that feels wrong in this scene – and the scene is the crux of the movie.

More complications follow, which I will leave for you to discover.

The chief delight in the movie is the joining of comedy and menace. The Mantegna character is keenly aware that one wrong step will result in instant death, but the Ameche character is able to save them both by simply being himself. There is a moment when Ameche and Prosky sit against a wall in the sun, two old men with their shoes off, and we sense that the local guy would almost rather not know that his visitor is not a crime syndicate don, because he plays the part so well.

I’ve been looking at a lot of films noir lately – those stylish black and white crime movies from the 1940s in which evil was found to lurk just below the surfaces of ordinary American lives. “Things Change” is a film in which the surface is evil, and goodness lurks beneath. The strangest thing about the film is the way the bond between the Ameche and Prosky characters seems to redeem the Nevada boss, to convince him if only for an afternoon that the real reason he got into crime was in order to demonstrate his loyalty to his friends.

If there is a flaw in the movie, it is Mamet” deliberation. A clever movie should always be quicker than its audience, and here there are moments when we have time to see ahead into the plot. Mamet has a genuine gift for movie direction – his films are not just illustrations of his dialogue, but have an energy of their own – however, timing is the area where he needs to tinker. His dialogue for the stage is written in such a way that an actor, reading it, is almost forced to time it the way Mamet imagined it. His characters punctuate their sentences by repeating the same words and phrases for emphasis. But in the movies, words exist in a different kind of time than on the stage, and Mamet tends to take play around and find what works for his dialogue.

The performances here are all wonderful, especially Ameche”.

Working in the midst of a cast that is otherwise entirely drawn from the Mamet stock company, he finds just the right note of bewilderment and cleverness. The character is never other than a confused old Italian shoeshine man, and yet time and again he saves himself by somehow finding the right thing to say. Mantegna, as his keeper, walks a fine line between desperation and comedy – and isn’t afraid to go broader in scenes where he pantomimes what Ameche should be saying and doing. And Prosky, his face a mask of jovial cunning, is touching in the way he wants to believe in this stranger who is so apparently phony. “Things Change” is a delicate balance of things that don’t easily go together: farce, wit, violence and heart. Here they do.