In his appraisal of Spike Lee’s “She Hate Me,” critic Nathan Rabin describes a “Morning Paper Auteur” thusly: “A filmmaker who picks up the morning paper, grows more enraged about each article he reads, and decides to make movies that forthrightly address every social ill in the known universe.” Dostoevsky-obsessed Lav Diaz is one such busy fellow. Something like annually, he crafts a many-hours-long opus about the ills plaguing Filipino society, wrapped up in some themes and ideas borrowed from Crime and Punishment. Why make a film about religious cults, abortion, sexual abuse, or Diaz’s own life as a filmmaker when you can combine them all, as he did in the six-hour “Century of Birthing”? Diaz is back at it in the four-hour “The Woman Who Left,” about prison life, regional crime, transgender identity, corruption, family, religion, poverty and murder.

The year is 1997—though the modern cars on the street say otherwise—and the place is a Filipino prison. Horacia (Charo Santos-Concio, a once-ubiquitous movie star in the Philippines whose career slowed down when she became president of one of the most popular TV networks in the country) is exonerated without warning, 30 years into a life sentence for murder. Turns out she was framed by one of her closest friends in the joint, who kills herself after confessing, with a little help from an ex-boyfriend named Rodrigo Trinidad (Michael De Mesa). She begs the few people she still knows not to tell anyone that she’s been freed because she wants to do some sleuthing into the frame-up before anyone knows she’s on the loose.

She catches a boat to the province where Trinidad has settled down with his family, starts dressing like a man to hide her identity, and cases the town. She gets information about her target from a host of unlikely sources, including an epileptic trans woman (John Lloyd Cruz), a shanty town salesman and a mentally challenged homeless woman (played by husband and wife Nonie and Shamaine Buencamino). Something interesting happens as she prepares to take some form of revenge on Trinidad for taking her life away; she starts to really get to know and like the street urchins who surround her during her nocturnal investigations. They start to worship her as she throws her money around to help their children see doctors or offers her home for them to take temporary shelter. She becomes a negative image of Trinidad, using her influence for good, instead of ignoring the struggling underclass.

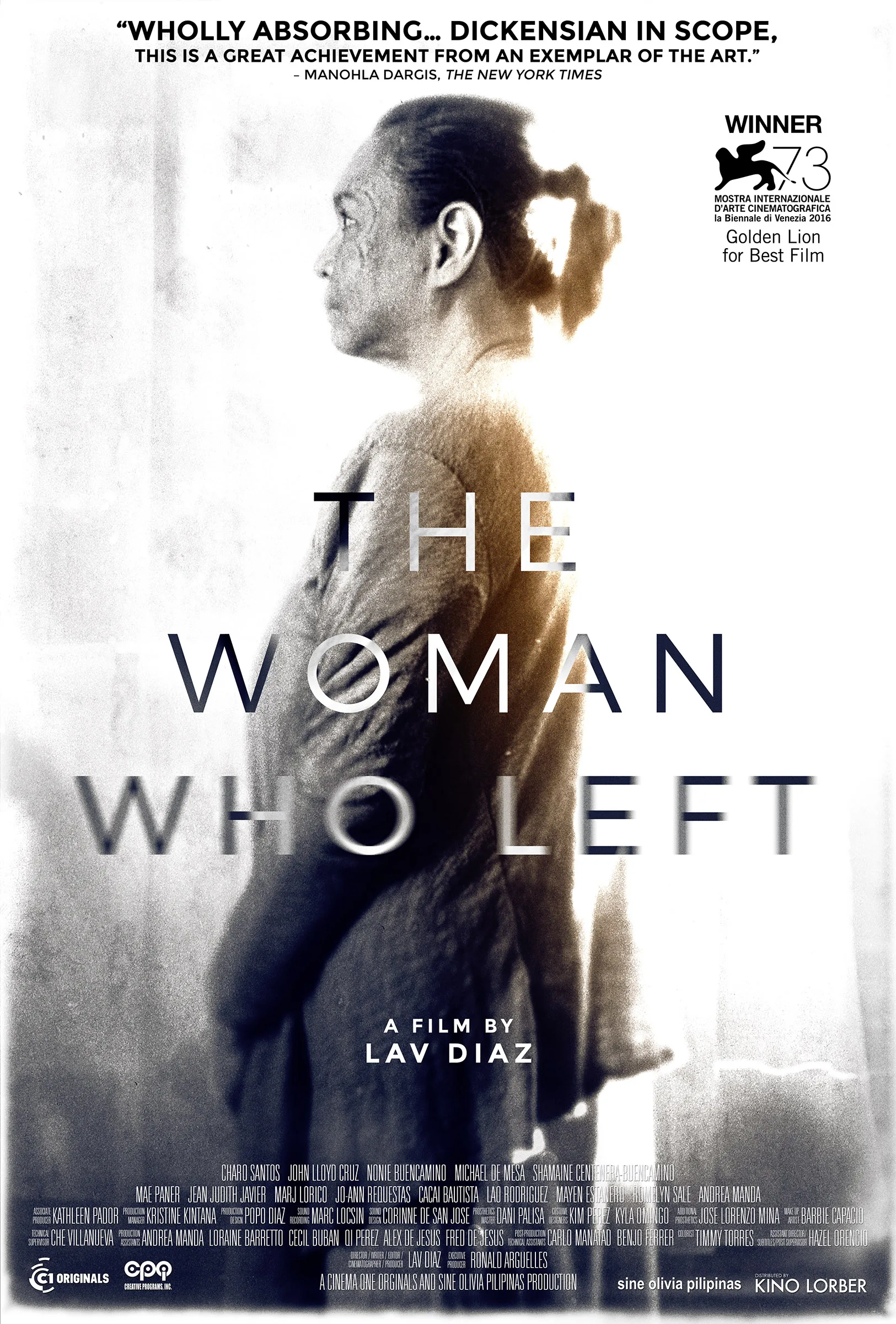

“The Woman Who Left” recently picked up the Golden Lion, the highest honor at the Venice Film Festival. As when Kim Ki-Duk’s “Pietà” took home the honor in 2011, one wonders whether the wandering focus and rough technical edges of the project only added to the feeling of authentic grimness both films cultivate. The sound of the film is a real mystery: sometimes it seamlessly transports us into the next image, other times the transitions pop loudly, like Diaz had to rush the film to premiere and couldn’t go back and smooth over the issues. This could simply be a product of Diaz shooting, directing, editing and writing the film and just not being able to spread himself equally across all tasks. His images definitely don’t suffer, whatever the case, as his usually silky black and white photography demonstrates. His street scenes are some of the most striking in the world cinema canon, and his compositions, which place his subjects in a diagonal trajectory across the Z and X axes, generate momentum even when the camera stays still for upwards of ten minutes.

The film makes heavy use of radio broadcasts to heighten the tension on the streets, constantly highlighting that there’s a rash of kidnappings unlike any the country has ever seen. Mother Theresa and Princess Diana are killed in the same bulletin. Diaz’s world is defined by senselessness, by the push and pull of gods exerting their power and then toppling. Horacia, with her random acts of kindness, seems to be the film’s version of Mother Theresa, though even she, in a fit of God-like cruelty, beats a mother of five in front of her children (the beating is augmented by inexcusably cartoonish sound effects). The woman will later forgive her for the violence, as if it’s just part of life.

“The Woman Who Left” isn’t as exhausting as other recent works by Diaz, like “Century of Birthing” or “Norte, The End of History,” and its grace notes are more sublime. In a four-hour movie that largely consists of people having drawn out, aimless conversations on empty streets, those are crucial. There’s the unforgettable bellow of the hunchbacked tinker hawking his wares, the sight of a drunken woman swaying beneath a street light, the way an addled mind seems to find footing in the repeated pronunciation of the word “Demonio,” Horacia trying to teach someone to sing “Somewhere,” from “West Side Story.” That song was covered by Tom Waits on his 1978 album Blue Valentine, which similarly creates and exists in an urban hellscape, where trash sweeps indifferently past god’s prisoners, bleeding from wounds they don’t remember collecting. The song means a lot to Horacia, hinting that her suffering might not be for naught if she can find some form of escape. Her reality is gone, and she attempts to rewire her identity after losing it in jail, trying and failing to project change onto her fellow street dwellers rather than directly confront herself. She accidentally undoes her most profound act of kindness by refusing to patch herself up instead of pointlessly seeking revenge.

The film finds something like transcendence in its final minutes, when Horacia flees the countryside to find her long-missing son in the city and must finally concede that she is still in some form of jail, though she is free. In a montage that recalls the conclusion of Michelangelo Antonioni’s “L’Eclisse,” we’re shown the “Missing” posters adorning dozens of street corners, blank walls and alleyways. Horacia’s presence is felt only through the sheer number of posters, painting the town with loss, trying to recreate one’s presence where humanity is rejected. Humans in the city come to look like insects busily running around, unable to change their lives, or do more than blend into an unfeeling urban design. Horacia’s devotion, like her signs, are ignored. Finally, she staggers, like the living dead, in a circle, the signs bearing her son’s face underfoot. His absence mocks her, literally becoming the ground beneath her feet. It will haunt her and support her, like the life she lost to incarceration.

These final moments abandon the rhythm Diaz had established over the preceding few hours as if to prove that life is always capable of slipping from our grasp and reorienting itself. No matter the steps we take to gain back some measure of control, we are no match for the aimless designs of the world upon which we so casually tread. That a film this busy can find such focus in its closing moments says that whatever Diaz’s methods of inspiration and creation, he knows exactly what he’s doing.