Throughout its majestic 188-minute running time, there is a profound sum of self-negotiation in Turkish auteur Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s “The Wild Pear Tree”; a slow-burning and unexpectedly humorous character study as reflective and impenetrable as anything in Ceylan’s filmography. I didn’t place the film’s intimidating length right at the top to scare you. Despite the weighty social and political concerns it grapples with, “Pear Tree,” much like Ceylan’s masterpiece “Once Upon A Time In Anatolia,” is breezily, almost absurdly watchable. Centered on a young and idealistic aspiring writer on a mission to get his first book published—you could say he is a literary Llewyn Davis who is unlikely to become Bob Dylan—the film trails ruminations on life, family, art, religion, politics and literature from dissimilar viewpoints, forming a multifaceted yarn deeply personal for Ceylan, and in a cumulative sense, for the viewer too. After all, it is impossible to not relate or turn a blind eye to young-age romanticism, as it deteriorates in the hands of unforgiving everyday realities on the way to its eventual defeat. Those of us above a certain age; we have been there.

That doesn’t mean the recent college graduate Sinan (Aydın Doğu Demirkol), the high-minded young author that leads the story (co-written by Ceylan, Akın Aksu and Ebru Ceylan), is all that likable or agreeable. Frequently traveling between the city of Çanakkale and his childhood town, Çan, where his parents and sister still live, Sinan seems to carelessly offend anyone he crosses paths with—thanks to his premature arrogance, he, not unlike Llewyn Davis, doesn’t even seem to be aware of his offhand insults. Even the way he refers to his first novel has some self-superiority baked into it: “Mine is one of those books that can’t be described in two sentences,” he says, helpfully classifying his supposedly unclassifiable work as “a quirky auto-fiction meta novel.”

In one scene, he pretty much implies to his old flame Hatice (Hazar Ergüçlü) that she now lives a pointless life in a forgotten town, before their prickly chance rendezvous resolves into a stolen kiss Hatice vengefully takes charge of. In others, he engages in fiery debates with old friends, town officials who might sponsor his book and religious figures in a stubborn manner, always convinced of his absolute righteousness. Persuaded of his own uniqueness, Sinan also looks down on his jovial, gambling addict father İdris (Murat Cemcir). A hapless man who seems to have failed every endeavor in life (his dead-end attempts to bring a dry well back to life are highly symbolic), İdris causes much embarrassment to both Sinan and his burdened mother Asuman (Bennu Yıldırımlar), with his heavy debts and past-its-prime wistfulness. But does the pear fall far from the tree? In familial beats closest to Ceylan’s early works featuring his own parents (namely, The Town and Clouds of May), “Pear Tree” slowly reveals the answer we had known all along.

Sinan’s allegorical decline starts when he reaches the height of his egotism in another serendipitous encounter; among the film’s most memorable. Our somewhat insolent literary hopeful, fresh out of a nationwide exam that could (but won’t) earn him a permanent teaching post, provokes Süleyman (Serkan Keskin), a famous, seemingly even-tempered author, in a local bookstore. With Sinan’s incessant, increasingly imprudent questions on the social and political function of literature, the relationship between an artist’s character and his/her work and so on, the debate takes a hostile turn, especially when Sinan persists in vaguely painting Süleyman as a sell-out (“a careerist,” Llewyn would say), who participates in dog and pony shows. I would argue that the eloquently verbalized (and extremely funny) anger Süleyman unleashes onto Sinan is some kind of a life-or-death manifesto every young artist needs to hear; not to give up on his or her enthusiasm, but to give it some real-world shape and direction. Süleyman doesn’t exactly suggest, “I don’t see a lot of money here;” but he unassailably tells Sinan to keep his unearned entitlement in check.

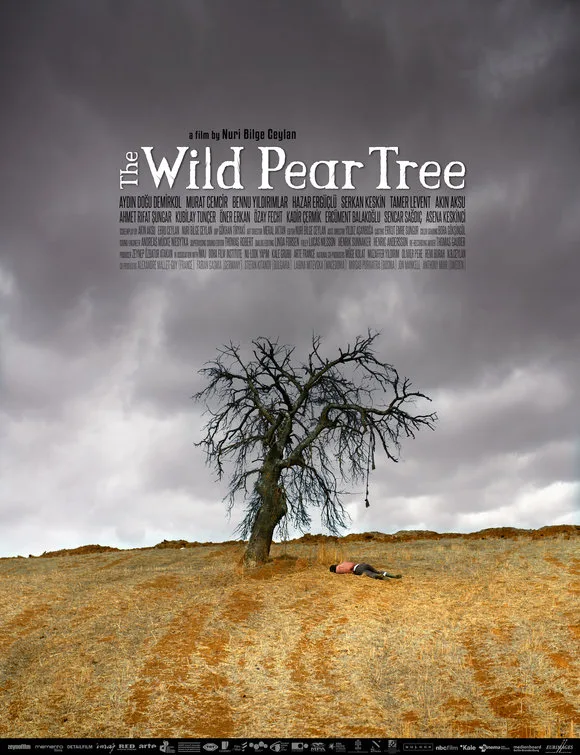

This scene is also where “The Wild Pear Tree,” always a bit dreamy thus far, spirals into occasional surrealism with subjective images of transitory realities. At one time, we can’t be entirely sure if we’re looking at a failed suicide attempt or a drunken body dosing off under the sun. Ants crawl on a sleeping baby, a Trojan horse monument serves as a hideaway and heavy rain follows cycles of gloom and fog amid vast landscapes, captured in unhurried and melancholically lit frames. A filmmaker known to translate stagey and decisively non-visual Chekhovian conversations into cinematic art of precise compositions, Ceylan, aided by his long-time cinematographer Gökhan Tiryaki, tends to every moody moment of his film with certain inevitability. Like his much quieter “Anatolia,” “Pear Tree” seizes loneliness everywhere as Ceylan sees it, and like his Palme d’Or winner “Winter Sleep,” it hangs onto every spoken word while the paths of Sinan and İdris painfully adjoin through the lost friendship of a loyal dog and a doomed book.

In a film where every character is intricately built and even those with single scenes can easily lead their own movie, it is odd that Sinan’s sister Yasemin (Asena Keskinci) never receives her defining moment. That neglect in the screenplay aside, “The Wild Pear Tree” is among Ceylan’s richest films, embellished with both local specificities and deeply Turkish concerns about art, politics and the social divide between cities and rural towns. Along the way, it lands on something universal about anyone who once settled down with a reality, seemingly lesser than the towering ambitions chased during youthful years of uncompromising purpose.