“The Wedding Singer” tells the story of, yes, a wedding singer from New Jersey, who is cloyingly sweet at some times and a cruel monster at others. The filmmakers are obviously unaware of his split personality; the screenplay reads like a collaboration between Jekyll and Hyde. Did anybody, at any stage, gave the story the slightest thought? The plot is so familiar the end credits should have issued a blanket thank-you to a century of Hollywood lovecoms. Through a torturous series of contrived misunderstandings, the boy and girl avoid happiness for most of the movie, although not as successfully as we do. It’s your basic off-the-shelf formula in which two people fall in love, but are kept apart because (a) they’re engaged to creeps; (b) they say the wrong things at the wrong times, and (c) they get bad information. It’s exhausting, seeing the characters work so hard at avoiding the obvious.

Of course there’s the obligatory scene where the good girl goes to the good boy’s house to say she loves him, but the bad girl answers the door and lies to her. I spent the weekend looking at old Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies, which basically had the same plot: She thinks he’s a married man, and almost gets married to the slimy bandleader before he finally figures everything out and declares his love at the 11th hour.

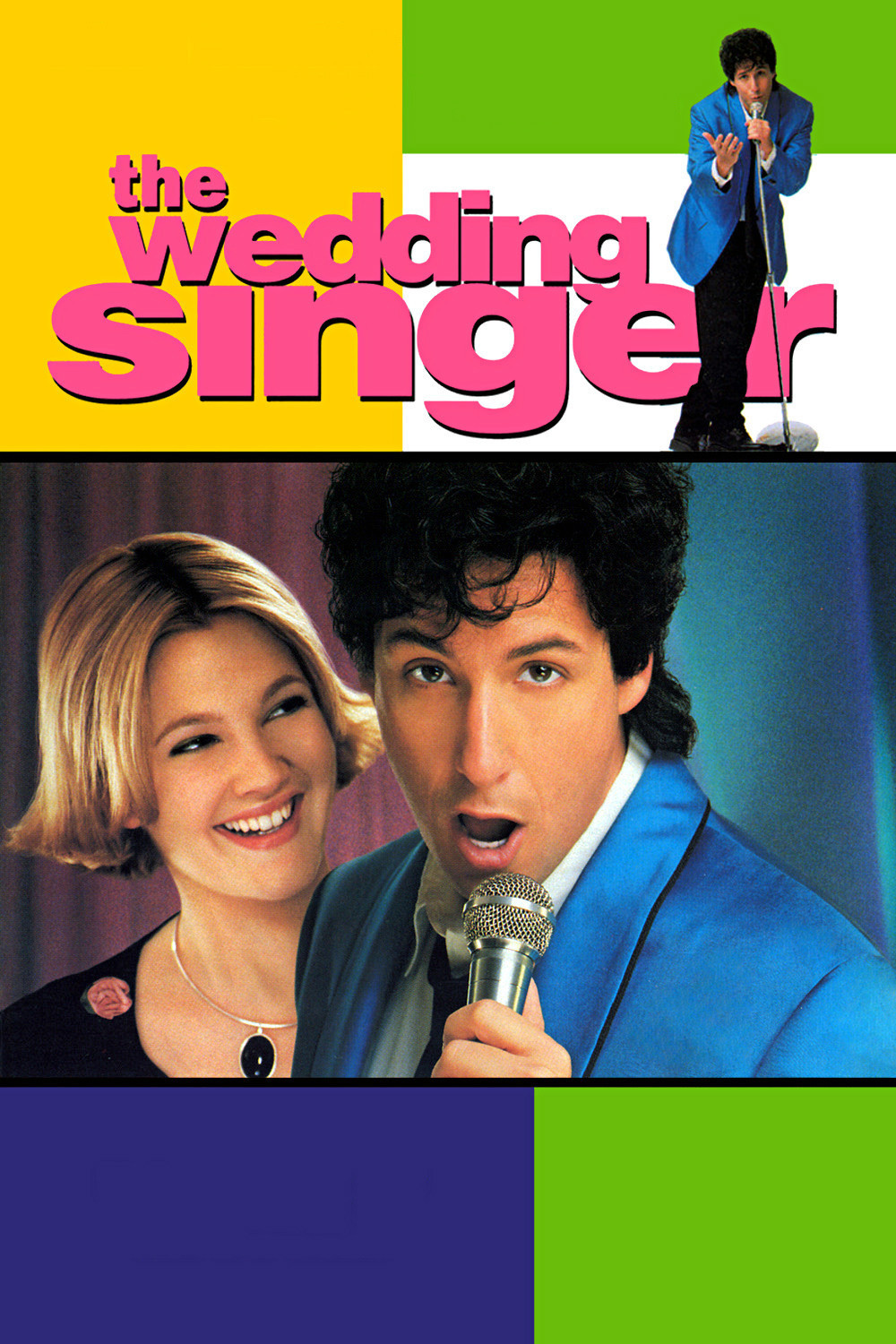

The big differences between Astaire and Rogers in “Swing Time” and Adam Sandler and Drew Barrymore in “The Wedding Singer” is are that (1) in 1936 they were more sophisticated than we are now, and knew the plot was inane, and had fun with that fact, and (2) they could dance. One of the sad byproducts of the dumbing-down of America is that we’re now forced to witness the goofy plots of the 1930s played sincerely, as if they were really deep.

Sandler is the wedding singer. He’s engaged to a slut who stands him up at the altar because, sob, “the man I fell in love with six years ago was a rock singer who licked the microphone like David Lee Roth–and now you’re only a . . . a . . . wedding singer!” Barrymore, meanwhile, is engaged to a macho monster who brags about how he’s cheating on her. Sandler and Barrymore meet because she’s a waitress at the weddings where he sings. We know immediately they are meant for each other. Why do we know this? Because we are conscious and sentient. It takes them a lot longer.

The basic miscalculation in Adam Sandler’s career plan is to ever play the lead. He is not a lead. He is the best friend, or the creep, or the loser boyfriend. He doesn’t have the voice to play a lead: Even at his most sincere, he sounds like he’s doing standup–like he’s mocking a character in a movie he saw last night. Barrymore, however, has the stuff to play a lead (I commend you once again to the underrated “Mad Love”). But what is she doing in this one–in a plot her grandfather would have found old-fashioned? At least when she gets a good line (she tries out the married name “Mrs. Julia Gulia”), she knows how to handle it.

The best laughs in the film come right at the top, in an unbilled cameo by the invaluable Steve Buscemi, as a drunken best man who makes a shambles of a wedding toast. He has the timing, the presence and the intelligence to go right to the edge. Sandler, however, always keeps something in reserve–his talent. It’s like he’s afraid of committing; he holds back so he can use the “only kidding” defense.

I could bore you with more plot details. About why he thinks she’s happy and she thinks he’s happy and they’re both wrong and she flies to Vegas to marry the stinker, and he . . . but why bother? And why even mention that the movie is set in the mid-1980s and makes a lot of mid-1980s references that are supposed to be funny but sound exactly like lame dialogue? And what about the curious cameos by faded stars and inexplicably cast character actors? And why do they write the role of a Boy George clone for Alexis Arquette and then do nothing with the character except let him hang there on screen? And why does the tourist section of the plane have fewer seats than first class? And, and, and. . . .