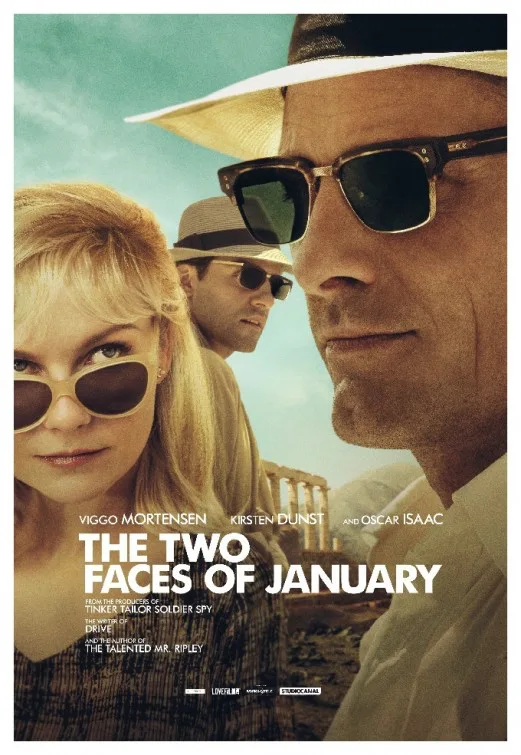

In “The Two Faces of January,” Viggo Mortensen wields a cigarette with the authority of Bette Davis and all the other great smokers of studio-era Hollywood. Gazing from under heavy-lidded eyes and a hat brim pulled low, Mortensen looks like a relic from that era, and cinematographer Marcel Zyskind lights him as such. The film is not only set in 1962, it looks as if it were made in 1962. Co-stars Kirsten Dunst and Oscar Isaac add to the verisimilitude of the period, as do the Greek locations. But it’s Mortensen and his smokes that seal the deal. Puffing away, he is dangerously sexy and morally dubious, the latter of which makes perfect sense as we are in Patricia Highsmith territory.

After adapting “The Wings of the Dove” and “Drive” for other directors, Hossein Amini makes his directorial debut with his take on Highsmith’s 1964 novel. For those unfamiliar, Highsmith created Tom Ripley and provided Alfred Hitchcock with the source material for “Strangers on a Train.” The characters in “The Two Faces of January” are cut from that same amoral cloth. The men are quick to irrational displays of emotion and jealousy, and though the women are more level-headed, they are also complicit in the evils those men do. Highsmith and Amini unleash the angriest gods of fate on these people, trapping them in a deceitful web of their own making. The scenery is pretty; the outcome of the story, not so much.

Chester MacFarland (Mortensen) and his wife Colette (Kirsten Dunst) are in Greece on vacation (or so they tell us) when they run into Rydal (Oscar Isaac). Rydal is a tour guide (or so he tells us) who speaks fluent Greek while fleecing his clueless female customers out of their money. Rydal takes an immediate shine to Colette, but it appears he’s more in lust with Chester’s affluent lifestyle than his wife. Rydal offers the MacFarlands a tour, and they reciprocate by inviting him to dinner.

Rydal spins a tragic yarn about how he wound up in Greece, a yarn that, to quote Birdie in “All About Eve” has “everything but the bloodhounds snapping at his rear.” It’s not clear if we’re supposed to buy Rydal’s yarn, but it becomes very evident that Chester lies to Rydal about what he does for a living. Turns out Chester is on the run for swindling lots of investors out of money. When Chester’s past catches up to him via a detective who visits his hotel, Chester’s actions have dire consequences for him and a clueless Rydal.

After Rydal drops the MacFarlands back at their hotel, he notices Colette accidentally left a piece of jewelry in the cab. Empowered by booze and horniness, Rydal makes a very wrong decision to bring it back to her. He buzzes the hotel room moments after Chester accidentally murders the detective. Chester convinces Rydal that the victim has merely passed out from drunkenness, and enlists the younger man to help him drag the detective back to his hotel room. Amini shoots this sequence like the darkest of farces; Rydal is so hypnotized by beauty and wealth that his common sense is overridden.

When another murder occurs, Chester is more than happy to pin it on the sucker he thinks he’s found in Rydal. However, Rydal proves to be as slippery and duplicitous as Chester, and part of the pleasure of “The Two Faces of January” is watching Mortensen and Isaac execute their game of cat and mouse. Dunst isn’t given much to do, but she makes the most of it by casting doubt on her innocence in matters of business and marital fidelity. She provides the catalyst for the games of male one-upmanship, battles that lead them from Greece to Istanbul.

“The Two Faces of January” culminates in a bizarre series of events. I haven’t read Highsmith’s book, but I’m now compelled to do so, if only to see if her ending matches the movie’s ending. I doubt it does, which isn’t a criticism. In fact, I found the ending fascinating. I won’t spoil it for you, but it is either an enormous deus ex machina or a subversively clever nod to the Hays Code rules that would have been very close to crumbling in the early ’60s. (Or maybe it IS the book’s ending?) If Amini’s goal was to make a movie that felt like a throwback to 1962, his ending puts a very fine point of closure on the idea. If not, the ending raises more questions than it answers.

Either way, it’s a great last scene for Mortensen, who manages to leave us conflicted about Chester when the credits roll. This is one of Mortensen’s best performances, and “The Two Faces of January” is one gorgeously rendered old-school feature.