It has been more than 30 years since Muhammad Ali last stepped into a boxing ring and yet he remains one of the most recognized and admired people throughout the world, even among those who otherwise have no particular use for the sport who championship he held on three separate occasions throughout his career. This is especially startling when you recall just how polarizing of a figure he was during the 60s when he inspired and inflamed people in equal measure both in and out of the ring. It is this period that is brought vividly back to life in the fascinating new documentary “The Trials of Muhammed Ali.”

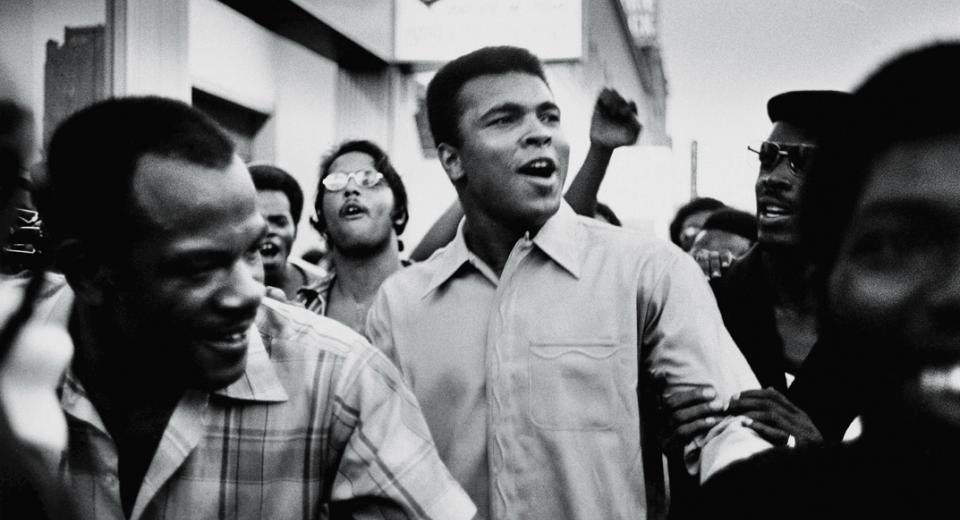

The thrust of the film comes from the period beginning in 1967 when, at the pinnacle of his profession, he was drafted by the U.S. Army to fight in Vietnam, an order that he rejected on the basis that he was a conscientious objector and that the war was nothing more than an extension of the white oppression that he had faced throughout his life and in which he felt he had more in common with the people he was being asked to kill rather than those doing the asking. (As he powerfully put it, “No Viet Cong ever called me ‘n****r.'”) This attitude outraged many and when his conscientious objector status was denied, he was convicted of evading the draft and had his boxing titles and status revoked, kicking off a long legal battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court before Ali was finally vindicated in 1971 and was able to reestablish his career at last.

As the film shows, however, Ali had been a provocative figure long before that draft notice arrived. After triumphing at the 1960 Olympics, the former Cassius Clay worked his way up the professional ranks while boasting of his skills in ways that bugged people who felt that athletes should be quiet and humble in public. (In one of the more amusing archival clips, no less of a figure than Jerry Lewis is seen chastising him during an interview on the comedian’s short-lived talk show.) Ali, however, was able to back up his verbal dexterity in the ring and soon took the championship from Sonny Liston and then infamously defended it against Floyd Patterson in a fight that some claim he deliberately stretched out in order to inflict maximum punishment on his opponent to get back at comments he had made before the fight.

In 1964, Clay made the controversial decision to covert to Islam and while the move made him a hero to many in the black community, it served to further alienate him from others who felt that Nation of Islam leader Supreme Minister Elijah Muhammad’s words and belief in black separatism were dangerous and divisive, especially at a time when tensions surrounding the civil rights movement were already at a peak. Even after he publicly changed his name to Muhammad Ali after his conversion, many would still call him by his original name, seemingly out of sheer obstinacy. And yet, Ali and his worldview would continue to evolve over time—he would associate with both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. and after the passing of Elijah Muhammad, he would begin to follow a gentler form of Islam than he once espoused when he would publicly call white people “devils.”

All of this information can be found in any number of biographies and historical references, although most previous films on Ali’s life have tended to give this period the short shrift in order to concentrate on his athletic achievements. (The current HBO film “Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight” does dramatize the Supreme Court while it debates its decision regarding Ali’s case.) What director Bill Siegel (who previously co-directed the 2002 documentary “The Weather Underground“) does is bring this era vividly to life via a canny selection of archival footage mixed with contemporary interviews with his brother, ex-wife Khalilah Camacho-Ali and current Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan.

We get to see the anger that his decision inspired in so many people—during a televised debate, David Susskind calls him a disgrace to his country—and the pride that it brought to others. We get a better sense of the personal and professional sacrifices that he made in order to stand up for his beliefs and the myriad methods that he used to support himself and his family during the time he was barred from the ring—in the most startling clip on display, we see a piece of “Buck White,” a short-lived 1969 Broadway musical that he starred in, that will leave most viewers simultaneously horrified and hungry for more.

Most importantly, “The Trials of Muhammad Ali” allows us a chance to see Muhammad Ali not as an icon but as a man willing to take a stand, even an unpopular one, for something that he believed in and one with the courage to stand up for his convictions in the face of almost unimaginable pressures. At a time when most professional athletes tend to be either self-absorbed jerks or people unwilling to take any sort of stand for fear of jeopardizing any endorsement deals, to see one brave enough to fight just as hard out of the ring as he did inside of it makes “The Trials of Muhammad Ali” a unique and inspiring viewing experience.