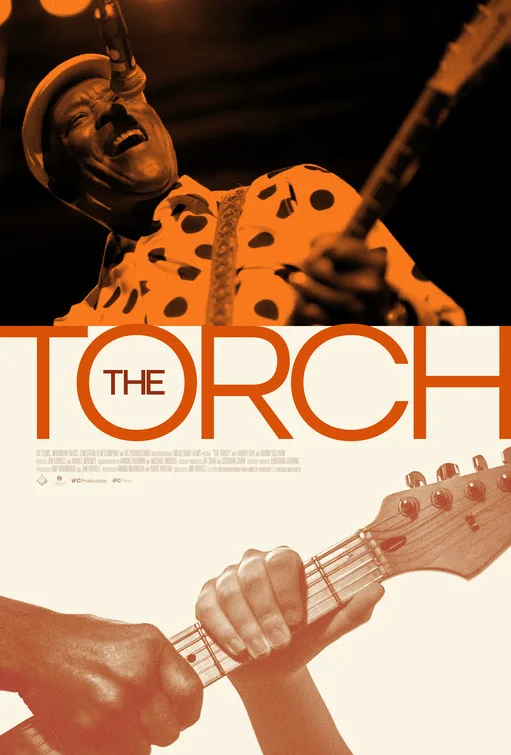

Blues guitarist Buddy Guy is a music legend, especially in Chicago. The winner of eight Grammy awards. A Rock and Roll Hall of Famer. Close friends with Mick Jaggers, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and so forth. A peer of B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, and Muddy Waters. And a staple at festivals and clubs across the country. You would think Jim Farrell’s documentary “The Torch,” a survey of his career, would solely feature him—but the frustratingly aimless film takes a far less successful path by looping in emerging guitarist Quinn Sullivan.

As you might guess, Sullivan is the titular torch: a wunderkind who gained fame at seven years old as a guitar playing prodigy. When you were slowly picking “Stairway to Heaven” in high school, this kid was shredding through the song’s solo. He first impressed Guy back in 2007 when the veteran player invited the New Bedford, Massachusetts native up to play with him. Ever since then, the charitable Guy, conscious of the dwindling ranks in Blues of young players, has been maneuvering to make Sullivan a star. Now, in his teens, however, the once wunderkind doesn’t know exactly what path he wants to take.

That’s ironic because much of Farrell’s film is directionless. Constructed around talking heads such as Carlos Santana, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi, and Tom Hambridge, his fellow musicians emphasize the guitarist’s legacy. Guy recalls his early life, how he migrated from Lettsworth, Louisiana to Chicago, wherein he met Muddy Waters, who took him under his wing.

It’s worth noting that Guy is sorta like the Buck O’Neil of the Blues. For decades, O’Neil, a former Negro League star, was best known as the keeper of the flame, the last man standing bearing testimony of the towering titans and landmark events that exist only in his memory. Guy speaks about those early Blues giants, and his place in their lineage, with the same hushed reverence and glee. Those recollections, on their own, should be enough to engross viewers, but they’re relegated to the sideshow in lieu of Sullivan, i.e. his childhood, his writing, and his aspirations. Thereby, undermining the far more intriguing component (Guy) for the aggressively banal (Sullivan).

Just as much as the subject, the verve of any documentary relies on its editing—a department where “The Torch” provides the dimmest of lights. The film struggles from scene to scene, incoherently tying elongated and repetitive montages of Guy and Sullivan performing together to hagiographic perspectives explaining how giving Guy is or the brightness of Sullivan’s future. Farrell equally hurts the documentary’s pacing with trite drone shots of the sprawling and sunny Southern landscape that are rendered so flatly, the inherent majesty of the countryside, its warmth and aura, is rendered into pure cliché. These literal scenery chewers make up the bulk of the nearly two-hour runtime’s fat without answering a few simple questions: What is the intended purpose behind each successive cut? How can they advance the story?

And yet, the missteps would be easier to forgive if the subjects were interesting. The legend of Guy as the last man standing only gains legendary status if the audience is allowed to learn about him. Apart from his relationship to the orbits of Muddy Waters or John Lee Hooker, we learn very little about Guy beyond where he was born and how he learned to play guitar. The bare-bones approach might satiate superfans, but for newcomers, the surface level storytelling offers them no additional sense of the man or the musician. What are his most memorable albums? How about a signature song? You won’t know unless you venture over to Spotify.

The culprit for the shallow intent springs from the very framing of the film. “The Torch” concerns the ways the genre needs to find new stars, new players to keep the genre relevant. But Sullivan isn’t an immediately fascinating subject. Separate what you might think of his music—to my eye he’s a clearly skilled guitarist, but his vocals can be categorized as being at home in a generic Christian pop group—his meek and quiet exterior, his milquetoast quotes, lack potency. You just don’t come away wanting to seek out his music.

It’s a major problem for a film that moves more like an advertisement for Sullivan than an incisive interrogation of the state of the genre, Guy’s career, or even the history of the Blues. Consequently, Farrell’s film stretches on-and-on, and on, without any sense of why we should take interest in Sullivan beyond Guy liking him. In doing so, “The Torch,” despite its best intentions, lights the way for no one.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.