Here is a rarity, a film about religion that is neither pious nor sensational, simply curious. No satanic possessions, no angelic choirs, no evil spirits, no lovers joined beyond the grave. Just a man doing his job.

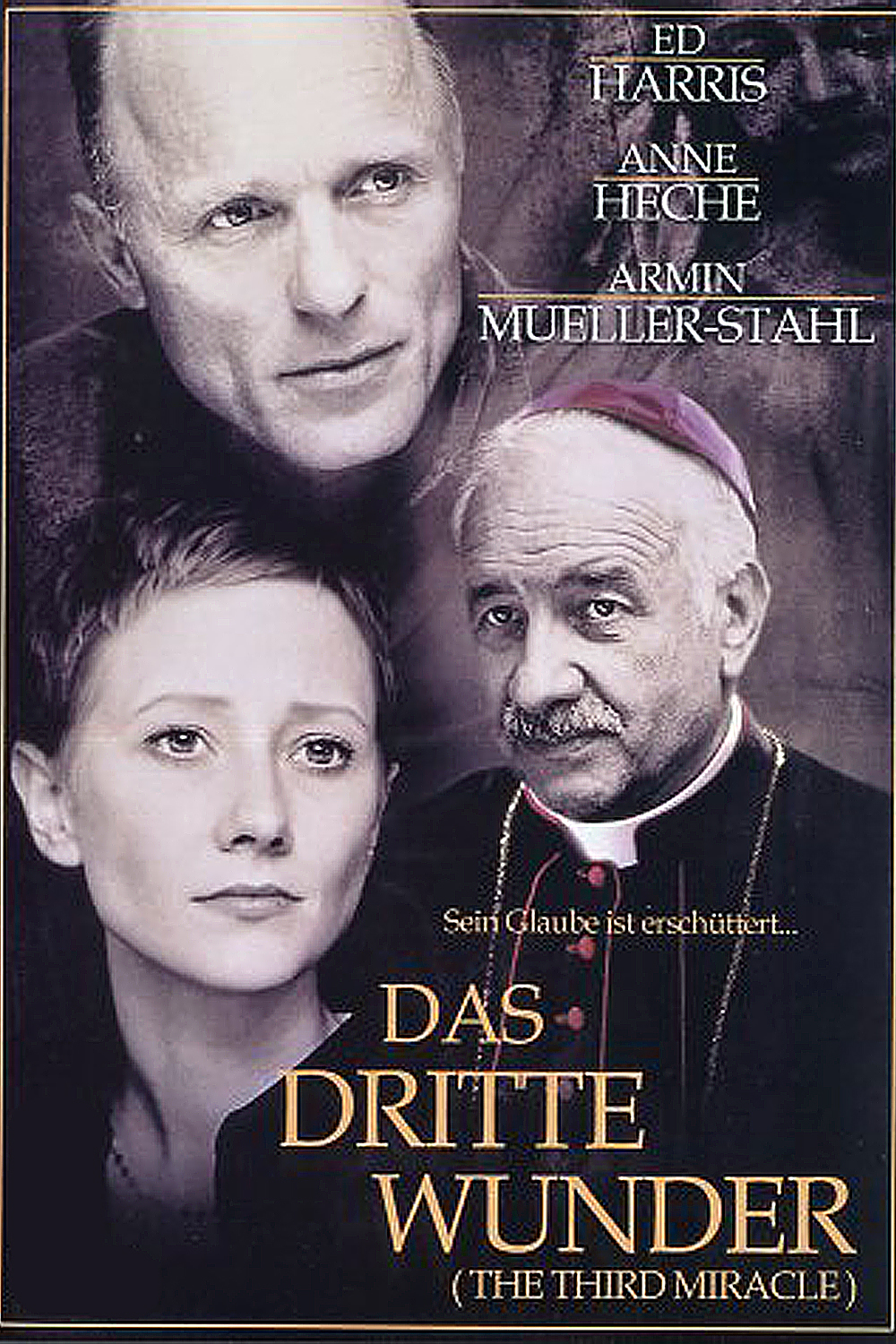

The man is Father Frank Shore, and he is a postulator–a priest assigned to investigate the possibility that someone was a saint. If he is convinced, he goes before a church tribunal and argues the case against another priest whose job is popularly known as “the devil’s advocate.” Ed Harris plays Frank Shore as a man with many doubts of his own. After deflating one popular candidate for sainthood, he became known as “the miracle killer,” and in his dark moments he broods that he “destroyed the faith of an entire community.” Now perhaps he will have to do it again.

It is 1979, in a devout Chicago ethnic community, and a statue weeps blood every November. That is the month of the death of a woman named Helen O’Regan (Barbara Sukowa), who is credited with healing young Maria Witkowski, dying of lupus.

Was Helen indeed a saint? Is the statue weeping real blood? What blood type? Father Shore is far from an ideal priest. We first see him working in a soup kitchen, having left more mainstream duties in a crisis of faith. Maybe he doesn’t believe in much of anything anymore–except that the case of Helen O’Regan deserves a clear and unprejudiced investigation.

Many a saint has made it onto holy cards with somewhat dubious credentials (did Patrick really drive the snakes from Ireland? Did Christopher really carry Jesus on his shoulders?). But in recent centuries, the church has become rigorous in recognizing miracles and canonizing saints–so rigorous that the American church has produced only three saints. In an age when many churches scorn science and ask members to simply believe, the Roman Catholic Church retains the rather brave notion that religion really exists in the physical world, that miracles really happen and can be logically investigated.

“The Third Miracle,” directed by Agnieszka Holland, was written by John Romano and Richard Vetere, based on Vetere’s novel. It has no scenes of Arnold Schwarzenegger trying to prevent Satan from impregnating a virgin with the Antichrist. Instead, it is about church politics, and about a priest who doubts himself more than his faith.

His life only grows more complicated when he meets Roxanne O’Regan (Anne Heche), the daughter of the dead candidate for sainthood. There is a delicate scene at her mother’s grave, where she and the priest have joined over a bottle of vodka to celebrate Helen’s birthday. Their dialogue does that dance that two people perform when they seem to be talking objectively but are really flirting. Finally Roxanne asks Frank if he believes all the church stuff. He asks her why she wants to know. “Because I can tell you like this,” she says, on exactly the right note of teasing and invitation.

Ah, but the infallible church is made of fallible men. Frank can harbor doubts and lusts and nevertheless think his job is worth doing. Up against him is the fleshy, contemptuous Archbishop Werner (Armin Mueller-Stahl), the devil’s advocate, who thinks three saints are quite enough for America. And then there is the problem of Maria Witkowski (Caterina Scorsone), who may have been cured of lupus but now is on life support after drug abuse and prostitution. “God wasted a miracle!” her mother cries.

Agnieszka Holland is a director whose films embody a grave intelligence; her credits include “Europa, Europa,” about a Jewish boy who conceals his religion to survive the Holocaust; “The Secret Garden,” based on the classic novel about a girl adrift in a house full of family secrets, and “Washington Square,” Henry James’ novel about an heiress who is courted for her money. She pays close attention to the emotional weather of her characters, and is helped here by Harris, whose priest talks as if he has finally decided to say something he’s been thinking about for a long time, and Heche, whose Roxanne approaches sexuality like a loaded gun.

In “The Third Miracle,” Holland is not much interested in getting us to believe in miracles, or in whether Father Shore is true to his vow of chastity. She is concerned more with the way institutions interact with the emotions of their members. People need to believe in miracles, which is why, paradoxically, they resent those who investigate them. Believers aren’t interested in proof one way or the other: They want validation. The fact that the church has refused to recognize the appearances of the Virgin at Medjugorje has done nothing to discourage the crowds of faithful tourists. There is a temptation (literally) for the church to go along with popular fancy and endorse the enthusiasms of the faithful. But to applaud bogus saints would be an insult to the real ones.

As Father Shore and Archbishop Werner face each other across a table in a boardroom, they are like antagonists in any global corporation. They would like to introduce a miraculous new product, but must be sure it will not damage the stock of the company. By seeing the church as an earthly institution and its priests as men doing their best to remain logical in the face of popular ecstasy, “The Third Miracle” puts Hollywood’s pop spirituality to shame.