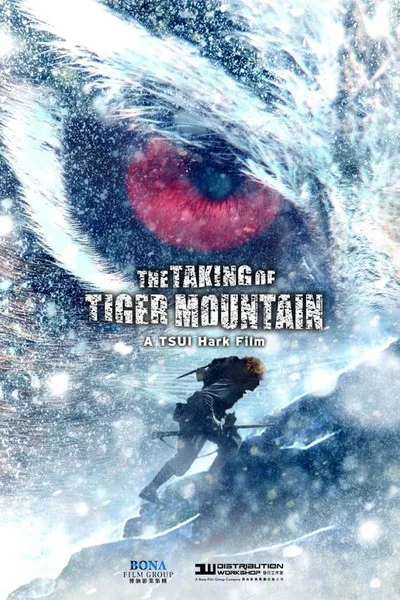

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, when the action cinema of Hong Kong was at its artistic and commercial peak throughout the world, arguably the key figure in their film industry was the hugely prolific Tsui Hark. As a producer, director and/or writer (and usually in some combination of the three), he was involved with many of the key cinematic works of this period—”Peking Opera Blues,” the “A Better Tomorrow” trilogy, “The Killer,” “Dragon Inn,” “A Chinese Ghost Story” and the jaw-dropping “Time and Tide” to name just a few. FIlled with breathtaking stunts, exquisitely choreographed, action set-pieces and weirdo humor, the films that he was involved in stood out amidst the flood of titles that emerged during that time. So distinctive was his work that during the brief period of time when he departed Hong Kong for America to direct a couple of Jean-Claude Van Damme epics (a ritual that many of the major HK players took part in at the time), the resulting films, “Double Team” and “Knock Off” were actually kind of entertaining in a cheerfully insane way.

In recent years, he has slowed down his output a bit—he now averages maybe one movie a year when he used to crank out two or three—but as his latest work, “The Taking of Tiger Mountain,” demonstrates, he has not lost any of his filmmaking fever. While the end result may be admittedly more uneven in spots than his best-known works, this lavish period piece contains enough thrills, spills and moments of cinematic grace that not only manage to push it through the rough spots but allow it to put most American action films of recent vintage to shame.

The story takes place in northwest China in the winter of 1946, a period in which civil war raged throughout the land between marauding gangs of bandits and the People’s Liberation Army, who were charged with bringing them down. The most feared of all the bandits is Lord Hawk (Tony Leung), who commands an army of thousands from his fortress atop Tiger Mountain, is armed to the teeth with weaponry that was left behind when the Japanese fled and has been laying waste to any village in the area unlucky enough to get in their way. Opposing Hawk is PLA Unit 203, a rag-tag group of perhaps 30 soldiers serving under the idealistic Jianbo (Kenny Lin).

Outgunned, outmanned and with time running short, Unit 203 launches a desperate final bid to defeat Hawk and his men by sending one of their men, Zirong Yang (Hanyu Zhang), to infiltrate Hawk’s stronghold by posing as a fellow bandit so that he can surreptitiously smuggle out information regarding the stronghold that the others can use to create a plan of attack. Although Zirong is quickly taken into Hawk’s confidence, some of the other bandits, especially Second Brother (Yu Xing), are suspicious of the newcomer and his motives, and he is in constant danger of being found out. Eventually, Hawk decides to launch a surprise attack on Unit 203 but the smaller group manages to prevails despite being outnumbered, which paradoxically only adds to the suspicion regarding Zirong. Just before Hawk can launch an unexpected second attack, Unit 203 decides to attack Tiger Mountain themselves during a New Year’s Eve celebration in a last-ditch effort to bring Hawk down.

Although inspired by historical incident, one does not need to be an expert in this particular period of Chinese history to understand what is going on in “The Taking of Tiger Mountain.” Once the opening expository scenes are passed, the film is essentially a typical guys-on-a-mission war movie in the manner of “Where Eagles Dare” and can be understood solely on that basic level–the good guys are good, the bad guys are horrible and anything remotely smacking of ambiguity is lost amidst all of the explosions and gunfire. Cutting through a lot of the potential narrative confusion for those without a working knowledge of Chinese history are the immensely charismatic and captivating performances by Hanyo Zhang as Zirong and Tony Leung as Hawk–the former does an excellent job of conveying the gravity of his situation without ever showing anything other than unflappable cool while the latter is clearly have a blast play the worst of the bad guys while still finding the occasional note of sympathy for him as well.

Some longtime Tsui fans may bemoan that his action set-pieces, which used to be done largely through insane and dangerous stunt work, now utilize a lot of CGI imagery, but, even if they lack the raw power of his earlier works, what he comes up with here is still pretty spectacular. There are three major action sequences in the film—the opening warehouse skirmish between Hawk’s men and Unit 203, the attack on Unit 203’s base of operations and their responding siege on Hawk’s mountain fortress—and no one will be going home disappointed after watching them with the most eye-popping moment being the bit where someone actually manage to jump across an enormous mountain crevasse on skis, albeit with a little help of a sort that I leave for you to discover. Another standout moment comes when Zirong finds himself battling a hungry tiger in the woods, a skirmish that finds the two fighting among the treetops—obviously, this is as ridiculous as can be but it is a bit of thrilling beauty to behold.

That said, Tsui has made a couple of tactical errors with his storytelling that do make the film a little uneven at times. Stylistically, he tries to have things both ways by presenting Unit 203 in starkly realistic terms while depicting Hawk and his army in highly stylized terms, right down to the ferocious hawks that swoop in to pluck out the eyes of those who offend him, and the juxtaposition between the two approaches is occasionally jarring. He also includes an odd modern-day framing device involving a young man traveling from New York to his homeland that is patently unnecessary. Weirdest of all, after the triumphant-but-realistic finale has been deployed and the end credits have begun to roll, Tsui provides us with an alternate ending in which good defeats evil in an over-the-top manner more suitable to a lesser James Bond film, as if he were afraid that the real ending somehow would leave viewers unsatisfied.

“The Taking of Tiger Mountain” may lack the raw power of Tsui Hark’s seminal work and that second ending is certain to send viewers out into the streets wondering what the hell that was all about. And yet, while it may not be a great Tsui film, it is certainly a good one, and that means that it is more interesting than most of the action fodder that hits the multiplexes these days. In fact, if the year’s upcoming cinematic spectacles are only half as exciting and energetic as this one, then 2015 will be a most memorable year indeed.