As one documentary after another attacks the International Monetary Fund and its pillaging of the Third World, I wish I knew the first thing about global economics. If these films are as correct as they are persuasive, international monetary policy is essentially a scheme to bankrupt smaller nations and cast their populations into poverty, while multinational corporations loot their assets and whisk the money away to safe havens and the pockets of rich corporations and their friends. But that cannot be, can it? Surely the IMF’s disastrous record is the result of bad luck, not legalized theft?

I am still haunted by “Life and Debt” (2001), a documentary explaining how tax-free zones were established on, but not of, Jamaican soil. Behind their barbed-wire fences, Jamaican law did not apply, workers could not organize or strike, there were no benefits, wages were minimal and factories exported cheap goods without any benefit to the Jamaican economy other than subsistence wages. Meanwhile, Jamaican agriculture was destroyed by IMF requirements that Jamaica import surplus U.S. agricultural products, which were subsidized by U.S price supports and dumped in Jamaica for less than local (or American) farmers could produce them for. That destroyed the local dairy, onion and potato industries. Jamaican bananas, which suffered from the inconvenience of not being grown by Chiquita, were barred from all markets except England. Didn’t seem cricket, especially since Jamaican onions were so tasty.

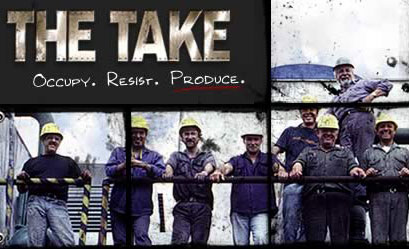

Now here is “The Take,” a Canadian documentary by Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein, shot in Argentina, where a prosperous middle-class economy was destroyed during 10 years of IMF policies, as enforced by President Carlos Menem (1989-1999). Factories were closed, their assets were liquidated, and money fled the country, sometimes literally by the truckload. After most of it was gone, Menem closed the banks, causing panic. Today more than half of all Argentineans live in poverty, unemployment is epidemic, and the crime rate is scary.

In the face of this disaster, workers at several closed factories attempted to occupy the factories, reopen them and operate them. Their argument: The factories were subsidized in the first place by public money, so if the owners didn’t want to operate them, the workers deserved a chance. The owners saw this differently, calling the occupations theft. Committees of workers monitored the factories to prevent owners from selling off machinery and other assets in defiance of the courts. And many of the factories not only reopened, but were able to turn a profit while producing comparable or superior goods at lower prices.

A success story? Yes, according to the Movement of Recovered Companies. No, according to the owners and the courts. But after Menem wins his way into a runoff election he suddenly drops out of the race, a moderate candidate becomes president, the courts decide in favor of the occupying workers, and the movement gains legitimacy. The film focuses on an auto parts plant and ceramics and garment factories, which are running efficiently under worker management.

Is this sort of thing a threat to capitalism, or a revival of it? The factories are doing what they did before — manufacturing goods and employing workers — but they are doing it for the benefit of workers and consumers, instead of as an exercise to send profits flowing to top management. This is classic capitalism as opposed to the management pocket-lining system, which is essentially loot for the bosses, and bread and beans for everybody else. Sounds refreshing to anyone who has followed the recent tales of corporate greed in North America. Is it legal? Well, if the factories are closed, haven’t the owners abandoned their moral right to them? Especially if the factories were built with public subsidies in the first place?

I wearily anticipate countless e-mails advising me I am a hopelessly idealistic dreamer, and explaining how when the rich get richer, everybody benefits. I will forward the most inspiring of these messages to minimum-wage workers at Wal-Mart, so they will understand why labor unions would be bad for them, while working unpaid overtime is good for the economy. All I know is that the ladies at the garment factory are turning out good-looking clothes, demand is up for Zanon ceramics, and the auto parts factory is working with a worker-controlled tractor factory to make some good-looking machines. I think we can all agree that’s better than just sitting around.