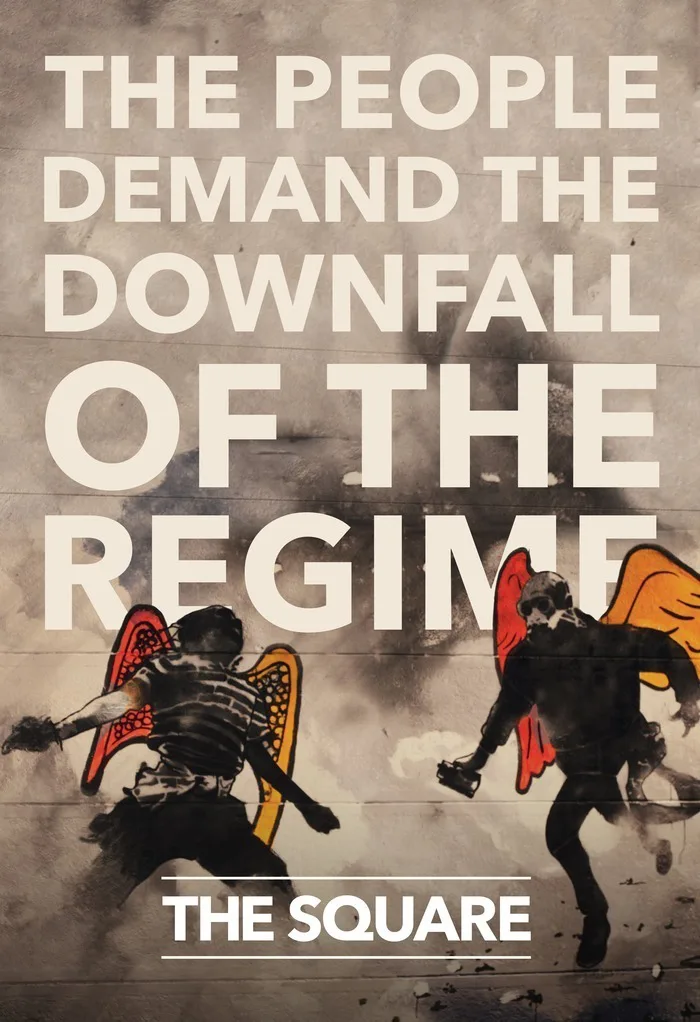

An entrancing and sharply crafted view of the political changes that have convulsed Egypt since the onset of the Arab Spring, “The Square,” by Egyptian-American documentarian Jehane Noujaim (“Control Room“), follows a number of individuals as they negotiate recurrent cycles of revolutionary hope succeeded by turmoil that sometimes turns harrowing and lethal. The result shows the human stakes and often punishing difficulties of challenging entrenched powers and interests.

Unlike Stefano Savona’s superb 2011 doc “Tahrir,” which focused on the heady times surrounding the ouster of former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in early 2011, Noujaim’s film also covers the two and a half years since. (After a version of “The Square” was shown this year at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Audience Award, Noujaim returned to Egypt and filmed through the summer, capturing the turbulence that accompanied the Egyptian Army’s ouster of Mubarak’s popularly elected successor, Mohammad Morsi. The film being released this week concludes with that very recent and dramatic footage.)

Of the geographic center of Noujaim’s film, someone remarks, “Tahrir is symbolic land.” That’s for sure. It seems that this Cairo roundabout, a rallying point for protests and flashpoint for violent confrontations throughout “The Square,” symbolizes the convergence of forces that contest to transform Egypt.

And not only does the square resemble a circle, but another geometric figure, the triangle, more accurately describes those counter-posed forces—the Army, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the people (i.e., politically engaged Egyptians who don’t belong to the other two groups).

As for the people: If this doc has a “star,” it is 20-something Ahmed Hassan, who would be a perfect lead if Frank Capra came back to life to make a movie about the Arab Spring. Blessed with a beaming smile and communicable ebullience, Hassan is the very picture of youthful revolutionary idealism and energy. In the 18 days leading up to Mubarak’s overthrow, he stalks the square day after day and night after night. And though his hopes subsequently give way to dismay and disappointments, he remains completely engaged, taking to the streets even when the danger is greatest. His courage and tenacity prove at once stirring and perplexing, since there is as yet no proof that world he wants is being born in the struggles we witness.

Among the other people Noujaim follows is an actual movie star, Khalid Abdalla, who appeared in “The Kite Runner,” “United 93” and “The Green Zone.” The son of a political activist who has lived in exile in England since being jailed in Egypt in the ’70s, Abdallah leaves London for Cairo when the campaign against Mubarak gains steam, and he remains there in an effort to help fashion Egypt’s future. As a celebrity and articulate English-speaker, he is often put in the role of spokesman for the revolutionaries, and that involves some astute commentary on the role of media in the conflict. As he says, “The battle is not rocks and stones. The battle is in the images…the stories.”

Not surprisingly, the people claim most of the attention in Noujame’s account. The Army is represented only by the occasional fatuous and laughably self-serving statement from a member of the officer corps.

The Muslim Brotherhood, meanwhile, has a more sympathetic and interesting representative in the person of Magdy Ashour, an activist who was tortured under Mubarak and is eager to participate politically once the tyrant is gone. A humble man of conscience and sincerity who wants to help the poor, Ashour finds his politcal ideals tested once the Brotherhood has power within its grasp.

As those who have followed events in Egypt will know, the ousting of Mubarak occurred when all three main factions were united. But thereafter the unity splintered and trouble ensued. Though the Brotherhood had been outlawed for many years, it was the nation’s largest and most potent political organization when democracy came. Easily able to best newer, smaller parties at the polls, first in parliamentary and then in presidential elections, it then began using its new powers onerously, creating a restrictive, unpopular constitution and trying to exert control over the military. When the Army reacted by deposing Morsi, violently suppressing his supporters (seen in the footage Noujaim shot over the summer) and reinstating military rule, they did so with a large measure of popular support—a bitter (if, one hopes, temporary) end to Egypt’s democracy.

Noujame’s chronicling of this recent history is brisk, mostly street-level and sometimes electrifying. Today it seems that the verite style she employs is almost de rigeur for filmmakers covering this sort of material, a pervasive fashion. And while its esthetic appeal is obvious, so are its limits. Without any commentary or expert analysis to help clarify matters, it’s often hard to grasp some elements and nuances of a complex and ever-shifting political situation.

But in conveying the immediacy and some of the representative personalities of that situation, “The Square” is vivid and memorable. No doubt most viewers will leave convinced that, while Egypt’s troubles may continue for years, the genie of liberty unloosed in 2011 will never be returned to the bottle.