How long has it been since you saw a movie that succeeds as pure story? That doesn’t depend on stars, effects or genres, but simply fascinates you with how it will turn out? Marc Forster‘s “The Kite Runner,” based on a much-loved novel, is a movie like that. It superimposes human faces and a historical context on the tragic images of war from Afghanistan.

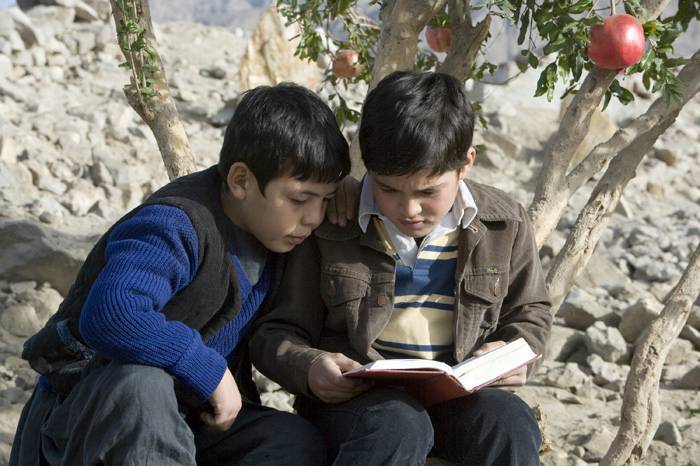

The story begins with boys flying kites. It is the city of Kabul in 1978, before the Russians, the Taliban, the Americans and the anarchy. Amir (Zekiria Ebrahimi) joins with countless other boys in filling the sky with kites; sometimes they dance on the rooftops while dueling, trying to cut other kite strings with their own. Amir’s friend is Hassan (Ahmad Khan Mahmoodzada), the son of the family’s longtime servant Ali, who has been with them for years and has become like family himself. Hassan is the best kite runner in the neighborhood, correctly predicting when a kite will return to earth and waiting there to retrieve it.

The boys live in a healthy, vibrant city, not yet touched by war. Amir’s father, Baba (Homayoun Ershadi), is an intellectual and secularist who has no use for the mullahs. Baba, whose kindly eyes are benevolent, loves both boys.

There is a neighborhood bully named Assef, jealous of Amir’s kite, his skills and his kite runner. On a day that will shape the course of many lives, he and his gang track down Hassan, attack him and rape him. Amir arrives to see the assault taking place, and to his shame, sneaks away.

Then a curious chemistry takes place. Amir feels so guilty about Hassan that his feelings transform into anger, and he tries insulting his friend, even throwing ripe fruit at him, but Hassan is impassive. Then Amir tries to plant evidence to make Hassan seem like a thief, but even after Hassan (untruthfully and masochistically) confesses, Baba forgives him. It is Hassan’s father, Ali, who insists he and his son must leave the home, over Baba’s protests.

The film has opened with the modern-day Amir, now living in San Francisco, receiving a telephone call from Rahim Khan: “You should come home. There is a way to be good again.” Then commences a remarkable series of old memories and new realities, of the present trying to heal the wounds of the past, of an adult trying to repair the damage he set in motion as a boy. For if he had not lied about Hassan, they would all be together in San Francisco and the telephone call would not have been necessary.

Working from Khaled Hosseini’s best seller, Forster and his screenwriter David Benioff have made a film that sidesteps the emotional disconnects we often feel when a story moves between past and present. This is all the same story, interlaced with the fabric of these lives. There is also a touching sequence as Amir and his father, now older and ill, meet a once-powerful Afghan general and his daughter Soraya (Atossa Leoni). For Amir and Soraya, it is instant love, but protocol must be observed, and one of the movie’s warmest scenes involves the two old men discussing the future of their children. I want to mention once again the eyes, indeed the whole face, of the actor Homayoun Ershadi, as Amir’s father; here is a face so deeply good, it is difficult to imagine it reflecting unworthy feelings.

What happens back in Afghanistan (and Pakistan) in the year 2000 need not be revealed here, but the scenes combine great suspense with deep emotion. One emblematic moment: A soccer game where the audience, all men and all oddly silent, is watched by guards with rifles. The film works so deeply on us because we have been so absorbed by its story, by its destinies, by the way these individuals become so important that we are forced to stop thinking of “Afghans” as simply a category of body counts on the news.

The movie is acted largely in English, although many (subtitled) scenes are in Dari, which I learn is an Afghan dialect of Farsi, or Persian. The performances by the actors playing Amir and Hassan as children are natural, convincing and powerful; recently I have seen several such child performances that adults would envy for their conviction and strength. Ahmad Khan Mahmoodzada, as young Hassan, is particularly striking, with his serious, sometimes almost mournful face. (The boy now fears Afghan reprisals for appearing in the rape scene, and the producers have helped to relocate him.)

One of the areas in which the movie succeeds is in its depiction of kite flying. Yes, it uses special effects, but they function to represent what freedom and exhilaration the kites represent to their owners. I remember my own fierce identification with my own kites as a child. I was up there; I was represented. Yet there is a fundamental difference between the kite flyer (Amir) and the kite runner (Hassan). Perhaps that sad wisdom in Hassan’s eyes comes from his certainty that all must fall to earth, sooner or later.

This is a magnificent film by Marc Forster, now 38, who since “Monster's Ball” (2001) has made “Finding Neverland” (2004), “Stay” (2005) and “Stranger Than Fiction” (2006). All fine work, but “The Kite Runner” equals “Monster’s Ball” in its emotional impact. Like “House of Sand and Fog” and “Man Push Cart,” it helps us to understand that the newcomers among us come from somewhere and are somebody.