Naomi is a great disappointment to her father. She is the student, the most learned, the most devout student of the respected old rabbi. But she hasn’t learned the most important lesson: How to be a submissive woman, to submit herself to the will of her father and her future husband. Even worse, she wickedly thinks she could someday be a rabbi herself.

There are hints in “The Secrets” that she knows well how her father’s beliefs worked in the life of her mother: “Often when I came into this kitchen, I found her weeping.” Naomi submits to her father the rabbi but not to her father the man. The rabbi has decided that his student Michael will marry Naomi. Naomi has no feeling for this man: She knows more than he does, but he treats her as a silly girl and piously asserts his narrow view of a woman’s role.

Naomi buys time. After the death of her mother, she postpones the wedding and persuades her father to let her spend some time in a seminary in a secluded town in Israel. Here she will come into her own as a natural spiritual leader, as a woman and as someone who discovers the difference between convenient and romantic love.

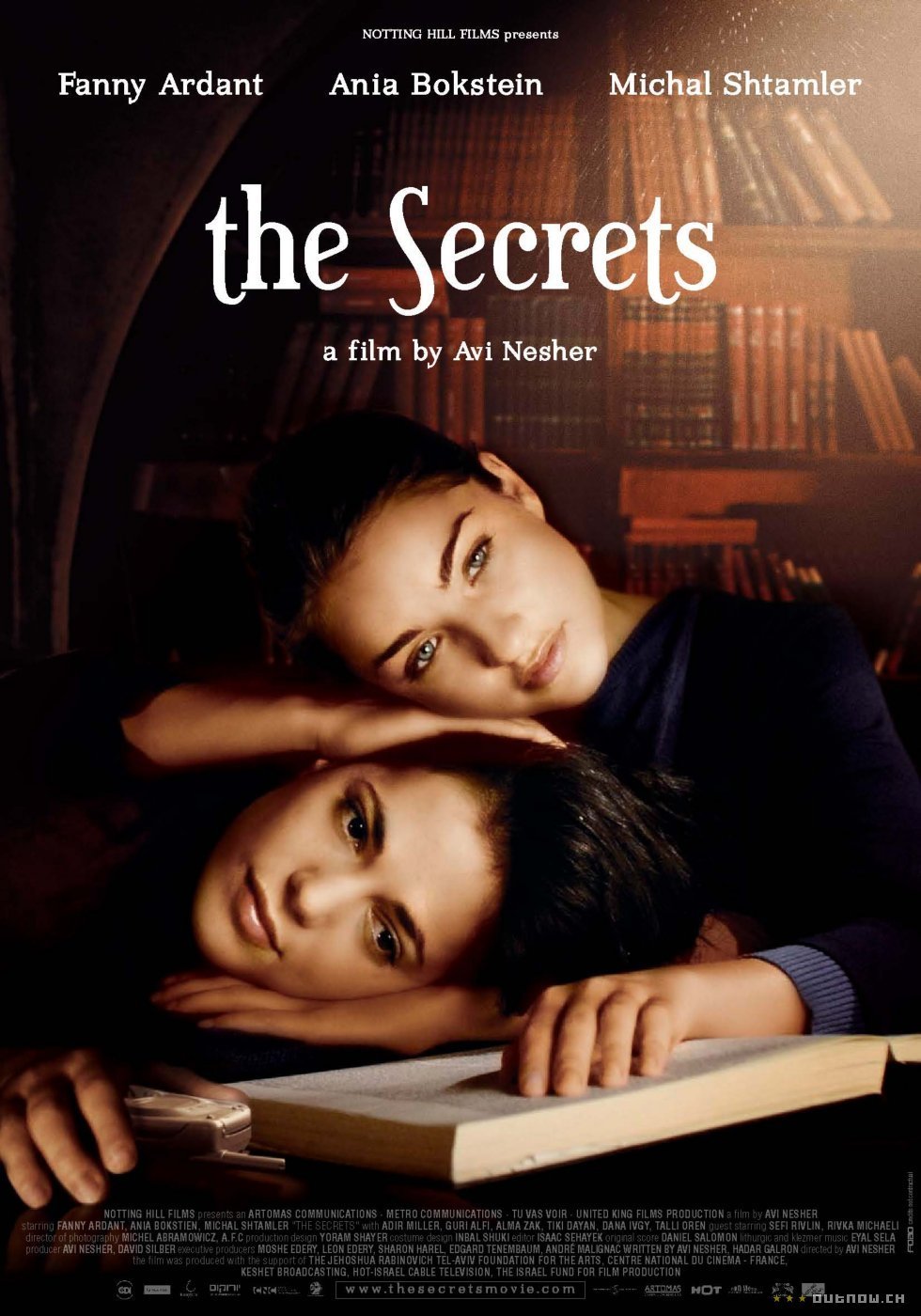

Avi Nesher’s “The Secrets,” a deeply involving melodrama, has all the devices to draw us into this story. In some ways, it is a traditional narrative. But it is more. It is gently and powerfully acted. And it is thoughtful about its characters, so that even though they follow a somewhat predictable arc, they contain surprises for us. They keep thinking for themselves.

Naomi (Ania Bukstein) seems at first a subdued, intellectual young woman, who believes explicitly in her father’s orthodoxy. But as she sees how it worked in her mother’s life and is working in hers, she experiences the basic feminist insight: Why a man but not a woman? It fascinates me that in some religions, men subscribe so eagerly to a dogma that oppresses women, and some women agree with it. Naomi does not agree.

At the seminary, one of her roommates doesn’t even think of agreeing. This is Michelle (Michal Shtamler), from Paris, with a chip on her shoulder. The two find themselves assigned to make daily meal deliveries to Anouk (Fanny Ardant), a very ill French woman, just released from prison and living in the town. Michelle discovers on the Internet that Anouk’s sentence was for murder. The details of the crime are left murky, but the woman desperately wants to be cleansed, and appeals to Naomi and Michelle to help her.

Their help for Anouk is the crux of the film. Even though she is not Jewish, Anouk seeks Jewish healing, and Naomi essentially acts as a rabbi in trying to help her. These scenes are the most moving in the film, involving a secret visit to an ancient cleansing pool, which, of course, is off limits to women.

Through this process Naomi and Michelle grow close romantically. As tension grows between Naomi and the loathsome Michael, Naomi’s father reacts with towering rage, and the movie becomes an argument against some elements of his style of Judaism. It will help clarify for some viewers that Judaism incorporates beliefs that are not all in agreement.

“The Secrets” is first of all continuously absorbing, which most good films must be. The performances by the three leading actresses are compelling, although Ardant is required to sustain the note of fatal illness perhaps too long. There’s a subplot involving a klezmer clarinetist that’s delightful. And one about the older woman in charge of the seminary that evokes an earlier generation’s beliefs about the limitations of women.

So “The Secrets” plays as a melodrama, and much more: a film about religious and sexual intolerance, about reconciling opposed beliefs, about matching the fervor of feminism against religious patriarchy, and even in some ways a social comedy. It contains an object lesson for the whole genre involving romance and the battle of the generations: Such films can actually be serious about something.