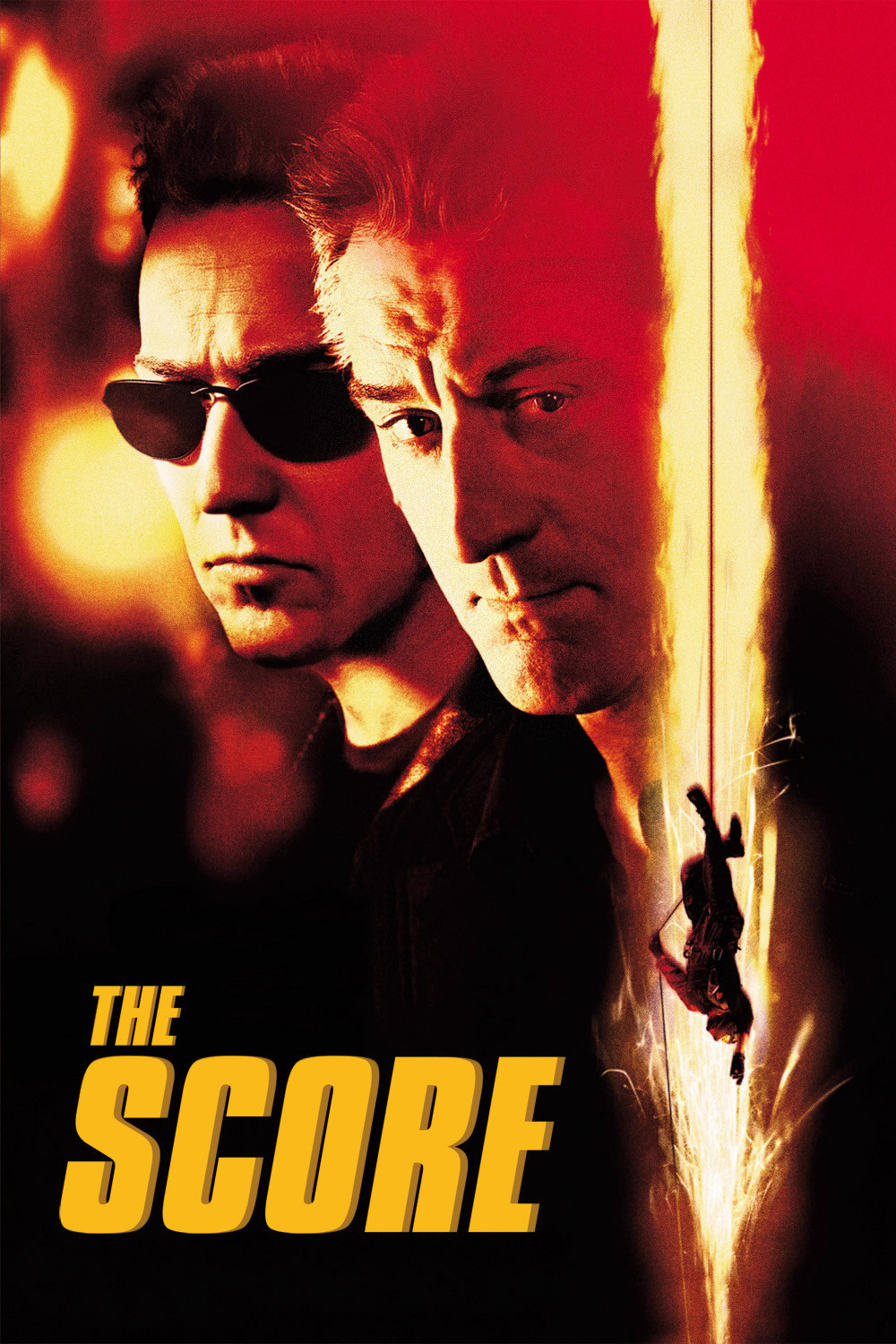

Robert De Niro stars as Nick Wells, who runs a jazz club in the old town of Montreal but is not, judging by his French, a native. His other job is as a specialist in break-ins, and the title sequence shows him trying to crack a safe in Boston. His rule: Never rob where you live. But now his old friend Max (Marlon Brando), a Montreal crime lord, comes to him with an offer. He knows of an invaluable antique in the Montreal Customs House, and of a way to steal it. The key to his plan: A contact named Jack (Edward Norton), who is a janitor at the building. Jack has become a coddled favorite there, by pretending to be “Brian,” whose speech and movement seem affected by some kind of brain damage.

These three performances are what they need to be and no more. It is a sign of professionalism when an actor can inhabit a genre instead of trying to transcend it. De Niro’s Nick is taciturn, weary, ready to retire after the proverbial one last score. Norton is younger and hungrier, and a show-off, who angers Nick by fooling him with the Brian performance.

Brando’s Max is a dialed-down Sidney Greenstreet character–large, wealthy, a little effeminate; his days of action are behind him, and now he moves other men on the chessboard of his schemes.

To these three characters the script adds a fourth, but does not use her well. This is Nick’s girlfriend, Diane (Angela Bassett), who flies into town for brief romantic meetings and is assigned the thankless task of saying yes, she’ll marry him–but only if he promises he has retired from his life of crime. Diane is so sadly underwritten that Bassett, a good actress, seems walled in by her dialogue. The filmmakers should have eliminated the role, or found a real purpose for her; as a perfunctory love interest, Diane is a cliche.

There are, however, a couple of flashy supporting roles. When it’s necessary to crack the security code used by the agency that guards the Customs House, Nick calls on a friend named Stephen (Jamie Harrold), who lives in a kind of cybernetic war room in his basement and boasts he’s the best: “Give me a KayPro 64 and a dial tone and I can do anything.” (There’s a running gag about Stephen’s mother shouting downstairs for him–a nod to De Niro’s character in “The King of Comedy“). Another supporting role, quieter but necessary, is Nick’s strong-arm man Burt, played by Gary Farmer, the big Canadian Indian actor.

The dialogue has a nice hard humor to it. When Nick meets a man in the park who is going to sell him a secret, the man comes with another man.

“Who’s that?” asks Nick.

“My cousin” the man says.

“See that man reading the newspaper on the bench over there?” says Nick, nodding to the gigantic Burt. “He’s my cousin. So we both have family here.” Brick by brick, the screenplay assembles the pieces of the heist plan. Obligatory elements are respected. We learn that the Montreal Customs House is the most impenetrable building in Quebec, and maybe Canada. We go on a scouting expedition in a labyrinth of tunnels under the building.

We’re introduced to high-tech equipment like miniature cameras and infrared detectors. We study the floor plan. We are alarmed by last-minute changes in plans, when the customs officials finally find out how valuable the treasure is, and install motion sensors and three cameras. And then the caper itself unfolds, and of it I will say nothing, except that De Niro’s character does incredibly difficult and ingenious things, and we are absorbed.

That’s the point. That we sit in the theater in silent concentration, not restless, not stirring, involved in the suspense. Of course there are unanticipated developments. The risk of premature discovery. Twists and turns. But there is not a lot of violence, and the movie honorably avoids a copout ending of gunfights and chases. It is true to its story, and the story involves characters, not stunts and special effects. At the end, we feel satisfied . We aren’t jazzed up by phony fireworks, but satiated by the fulfillment of this clockwork plot that has never cheated. “The Score” is not a great movie, but as a classic heist movie, it’s solid professionalism.