Walking next to some thick shrubbery recently, I saw a foot moving behind the bushes, and became aware of a warren of cardboard and old blankets in the shadows: There was a person living there. I felt embarrassed, as if I’d walked in on somebody using the toilet.

And I understood something about how we respond to the homeless.

We have a tendency to look away, to not see these people huddled in doorways or holding crude signs on which they have written their life’s tragedy.

They embarrass us, standing before us naked, having been stripped of home, employment, family and proper costume. They are simply unadorned human beings, without social titles and roles, and we have no script for dealing with them.

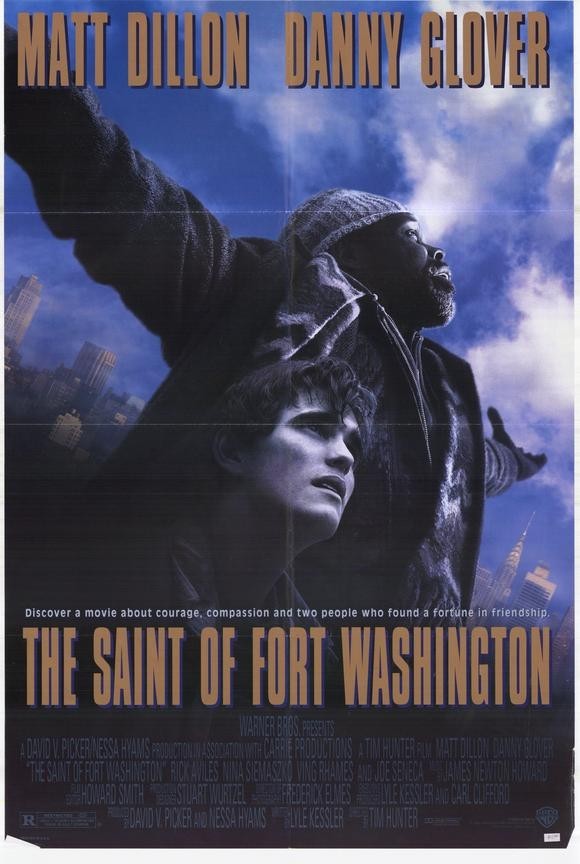

The coining of the word “homeless” has been useful, since we are not comfortable in this society with words like beggar; at least a name has been given to their condition. Yet homelessness is the last in line of their problems, coming in many cases after mental illness, addiction, or the simple inability to find work. In the new film “The Saint of Fort Washington,” for example, one of the heroes is mentally ill, and the other is a Vietnam veteran who has lost everything in his life, one piece at a time, until now all that’s left is chronic pain from a war wound.

The movie seems knowledgeable about the daily realities of homelessness. If you have ever stopped your car at an intersection and been approached by men with squeegees, offering to clean your windshield, you may have wondered who these guys are, where they come from, and where they go at night. This movie knows.

The story is set in New York and involves Jerry (Danny Glover), a black Vietnam veteran who has had one bad break after another, and Matthew (Matt Dillon), whose life is uprooted when a wrecker’s ball comes crashing through the walls of his SRO hotel. Matthew has mental problems; he hears voices. He receives government assistance to pay his rent. But without an address, he cannot receive checks, and without a check, he cannot obtain a new address – a Catch-22 that sends him onto the streets.

Jerry, an older man with great experience in urban survival, notices Matthew and takes him under his wing. The two become buddies, and Matthew shows him the ropes, including the windshield cleaning routine. Usually they are ignored by motorists, or cursed, but sometimes they get a quarter or a dollar, which they spend on fast food or an occasional drink. At night they sleep rough, or, in cold weather, in the Fort Washington Shelter, an armory where hundreds of beds are lined up, row after row.

The problem with sleeping in a city shelter, we learn, is that it’s more dangerous than the streets. The strong brutalize the weak, and you are likely to awaken without shoes or other possessions. Fort Washington is ruled by a vicious giant named Little Leroy (Ving Rhames).

The relationship between Jerry and Matthew has echoes of the friendship in “Of Mice and Men”; Matthew sees that Jerry has a childlike innocence, and grows protective of it. The two men gradually reveal details of their life stories, and engage in rambling discussions about the nature of life itself. And there are many scenes in which the director, Tim Hunter, shows in semidocumentary detail how the homeless survive. One myth is broken: These men are not lazy, and, in fact, work longer and harder hours than many of the employed motorists who roll up their windows and ignore them.

The film is well-acted. Glover and Dillon make characters who seem comfortable with each other; it is easier to fight the world together. Both actors resist any temptation to reach for pathos in their roles. The Glover character, angered at being cheated out of a small business, has great fury at the world, but has learned mostly to control it; he needs someone to care for, and comes to love the younger man almost as a son. And Dillon, saddled with sainthood in the film’s title, plays against sentimentality most of the time.

The film’s flaw, I think, is to spend too much time with the melodrama surrounding the bully of the Fort Washington Shelter. The screenplay settles into a good guy/bad guy rhythm, in which most of the developments are predictable. No doubt that is thought to be more commercial. But I was more interested in the scenes that showed, in knowledgable detail, exactly how it is possible to stay alive in the city using nothing but your wits and the uncertain generosity of strangers. Since seeing this movie, I’ve found myself letting those guys at intersections wash my windshield. Big deal: I’ve changed exactly nothing about the underlying situation. But I feel like I know who they are.