If a book were to be written about filmmaker Amir Naderi, it might be called A Cinema of Ecstatic Vision. Naderi is a true original; no other director this side of Martin Scorsese seems as purely in love with movies and as entranced with the medium’s kinetic possibilities. Born in Iran, he was a key figure in the explosion of talent known as the Iranian New Wave (1969-1979). Though he moved to the U.S. in the 1980s and later made movies there and Italy and Japan, before he left his native land he made “The Runner,” post-Revolutionary Iran’s first masterpiece and one of the most exhilarating films in cinema history.

“Everyone who sees this film falls in love with it,” a friend recently remarked. That’s likely true, but unfortunately few Americans have had the chance to become so smitten—till now. The reason why is easily explained. Though Iranian cinema’s post-Revolutionary revival continued apace from the mid-‘80s on and produced some extraordinary films, it wasn’t until Jafar Panahi’s “The White Balloon” won the Camera d’Or at Cannes in 1995 that distributors began to take notice and Iranian films became an international art-house phenomenon

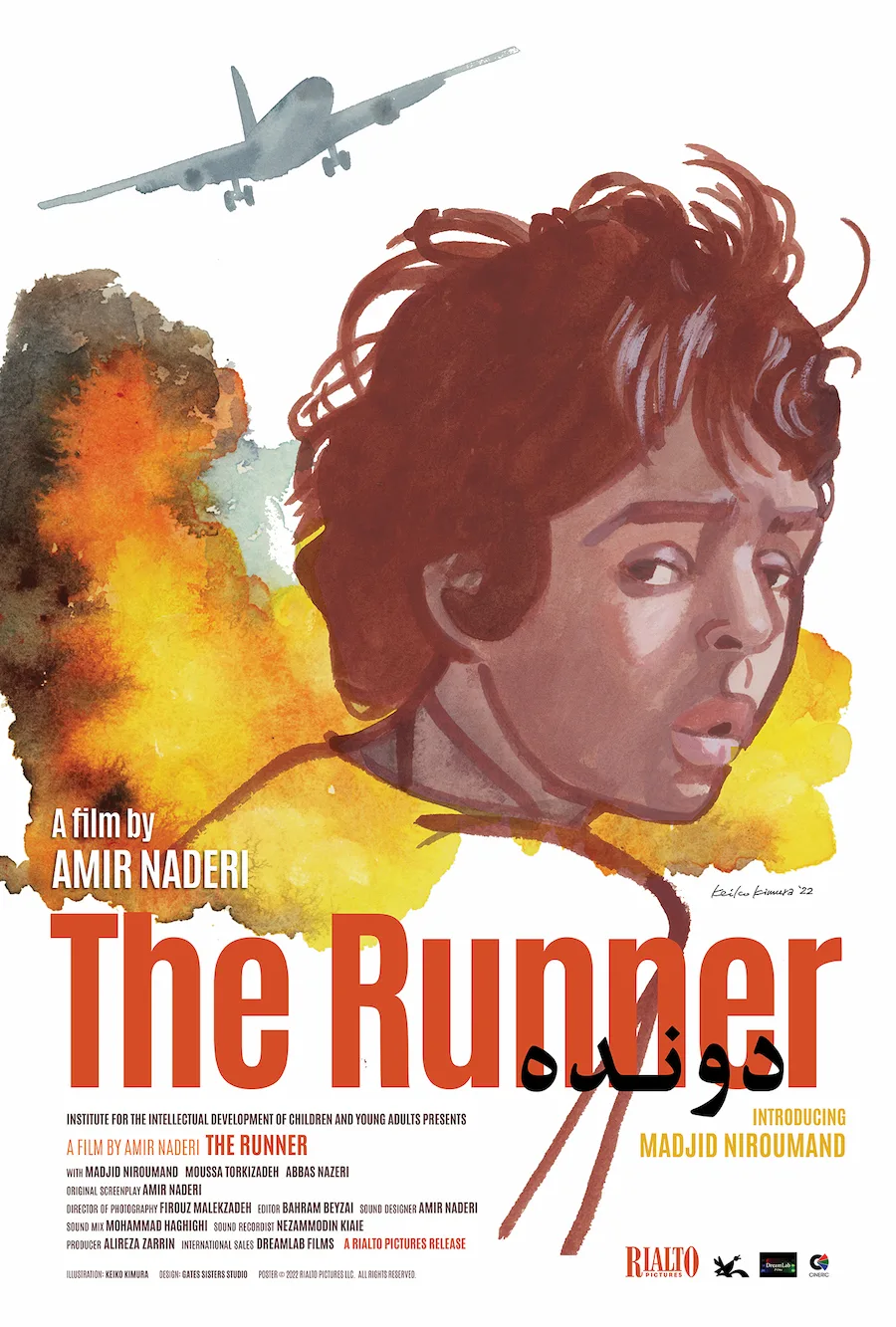

But if “The Runner” was among the films that arrived too early to benefit from that attention, it has retained a legendary reputation among cinephiles and admirers of Iranian cinema. And now, it is finally getting a U.S. theatrical release courtesy of Bruce Goldstein’s Rialto Pictures, which specializes in the reissue of renowned cinema classics.

The film is a natural for the audiences of New York’s Film Forum, where it will open on Friday, but I would like to put out a special alert urging every film student in the New York area (production or cinema studies) to see “The Runner.” To say that the 1984 movie doesn’t seem at all dated is almost an understatement. I can’t think of any 2022 film that radiates so much joy in the act of filmmaking, or that can serve as such an electrifying inspiration to younger artists.

It begins with a shout—of wonderment mixed with desperation—emitting from a boy watching tankers far out on the shimmering Persian Gulf. This is 11-year-old Amiro (an amazing Madjid Niroumand), an orphaned ragamuffin who lives by his wits in coastal Abadan. (Because the Iran-Iraq war was raging around the city when the film was made, Naderi was obliged to film in other locations.)

The tale is autobiographical. Like memories drifting up from a dream, the narrative’s impressionistic torrent shows us fragments of the boy’s haphazard existence: making money by selling water, shining shoes or fishing empty bottles from the sea; playing with some kids and enduring tense rivalries with others; making his solitary household on the upper deck of a gigantic abandoned tanker; observing the comings and goings, the fashions and music of exotic foreigners who pass through the busy port city (the film offers a flavorful glimpse of pre-Revolutionary Iran); trying to learn the alphabet so he can read the aviation magazines that fascinate him.

Capturing one of the key paradoxes of childhood, “The Runner” paints Amiro’s existence as one of both freedom and confinement. Because he has no adult telling him what to do, the boy can range exuberantly across a stunning landscape of sea, plains, and city. Yet he’s smart enough to know that this place offers him no future and that poverty is the ultimate trap. His gaze repeatedly returns to means of escape—trains, ships and, most entrancingly, airplanes.

Throughout, what Naderi shows us of Amiro’s life is not nearly as compelling as how he shows it. Rendered in Firooz Malekzadeh’s exquisite color cinematography, Amiro’s environs are full of dazzling light and colors, with the clear edges of a hyperrealist painting. But Naderi’s most distinctive technique lies in his use of motion (here again Scorsese comes to mind), especially rapid lateral tracking shots and shots, for example, from the inside of a train as it speeds away from a crowd of boys running pell-mell after it. Obviously the peripatetic Amiro is the runner of the title, but the same word could fit the film itself, which has a breathless headlong gait (the editing is by Bahram Beyzai, one of Iran’s greatest filmmakers).

Lest anyone suspect that Naderi stumbled upon this riveting visual language on his own, it’s worth noting that he was known as the most avid cinephile among major pre-Revolutionary directors. In Iran, I heard the story of how he once drove a VW bug from Tehran to London to be first in line for the opening of Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.” When Iranian films began reaching international festivals in the ‘80s, critics often detected the influence of the two most significant previous movements in post-WWII cinema, Italian neorealism and the French New Wave. “The Runner” evidences the impact of both. Like De Sica’s “Shoeshine,” it was shot on real locations and uses nonprofessional kids in a tale of social outcasts. As in Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” its story is derived from the director’s own life. (The influence of “Pierrot le Fou” and other Godard films may be felt in the film’s visuals.)

During the Iranian New Wave period, Naderi directed big movies with movie stars, but he also started the autobiographical strand in his work with a film called “Harmonica,” which also features a character called Amiro. (His teenage years were dramatized in “Experience,” which he scripted and Abbas Kiarostami directed.) After the Iranian cinema was effectively destroyed in the 1979 Revolution, there was some doubt whether it would be resurrected under the Islamic Republic. In May 1981, Naderi, Kiarostami, Beyzai and other New Wave veterans published an open letter urging the regime to reconstruct the film industry. Within two years, their advice was heeded and filmmaking resumed in Iran.

But then came the question: what kinds of movies to make? In separate interviews, Naderi, Kiarostami, and Beyzai recalled to me their mutual decision to make movies about children since the regime’s new content restrictions (e.g., obliging women to wear hijabs even when they wouldn’t in real life) made dramatizing adult lives too problematic. This tactic resulted in three masterpieces that became the post-Revolutionary cinema’s first international calling cards. “The Runner” came first, followed by Kiarostami’s “Where Is the Friend’s House?” and Beyzai’s “Bashu, the Little Stranger.”

Although all three films deal with kids in impoverished circumstances, there’s a certain exuberance to them, as if the directors were not only were excited to be making movies again but sensed that they were creating a new cinema. Yet everywhere in their innovative artistry there are echoes of Iran’s artistic past, especially poetry. For me, watching “The Runner” always brings to mind Rumi, whose verse is often described as ecstatic. Naderi’s work has a similar spiritual energy and belief in the transformative power of art. It is a vision of cinema that never ceases to amaze and inspire.

Now playing in select theaters.