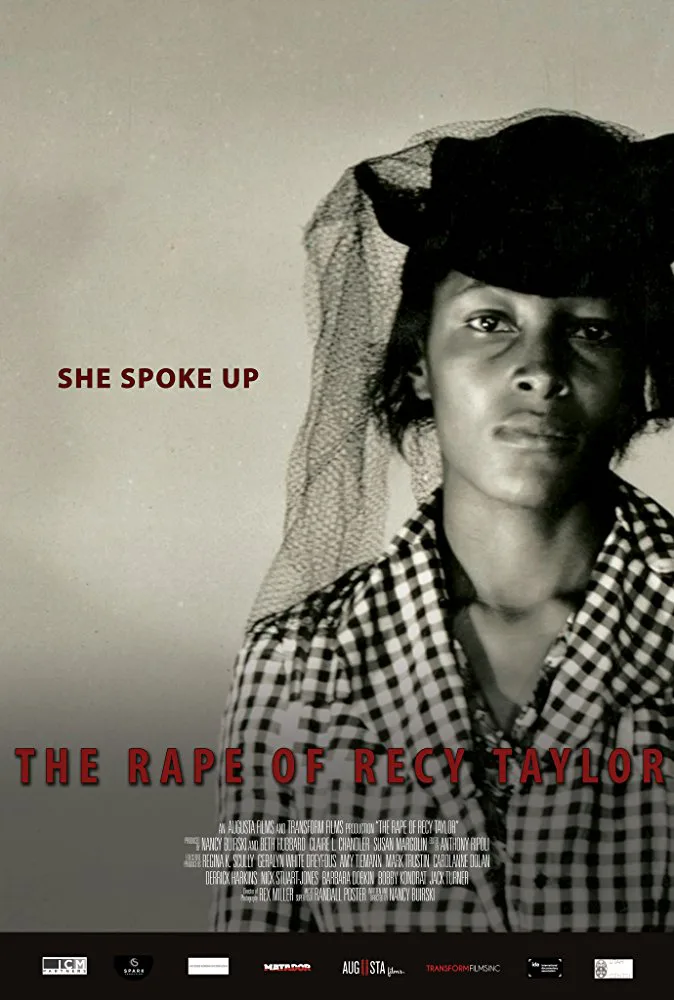

Nancy Buirski’s documentary “The Rape of Recy Taylor” is a heartfelt work on a powerful subject: the rape of a black woman in Abbeville, Alabama in 1944 by a group of white men, a crime that disappeared into the larger history of the south for racial reasons. It’s also a testament to how hard it is to make a documentary about an event for which few visual records exists.

The subject is Recy Taylor, a 24-year old woman who was kidnapped on her way home from church and assaulted by six men—a crime that was later rationalized as consensual sex on grounds that Taylor was a prostitute. (She wasn’t.) To reconstruct this outrage, Buirski weaves together interviews with mostly elderly people from that time and place, in particular Taylor’s brother Robert Corbitt and his sister Alma Daniels (who died in 2016). Taylor herself also appears fleetingly, though she’s she’s not a lucid presence. The movie also gives us a sense of the initial investigation, which was overseen by none other than future Montgomery bus boycott instigator Rosa Parks, sent from Montgomery, Alabama in hopes of drawing national press attention to the crime—the only way, then and now, to get justice for marginalized people who live outside of major cities.

This is all fascinating. But you quickly get the sense that Buirski either doesn’t find it interesting enough to let it stand on its own or else is afraid that audiences will rebel against too many bare-bones elements.

If the latter, she might not be wrong. There was a time when it was considered OK to build a story from the past around images of people talking about the events, plus still photographs and new film footage of the places where they happened. You still see documentaries like that on TV sometimes (though they are very likely to include re-creations with actors). Nevertheless, the approach she’s chosen here is more often irritating than illuminating, and at times suggests a lack of faith in the inherent power of the elements she has on hand.

The personal testimony and historical reconstruction in this film are constantly being intercut with footage from low-budget black-and-white movies produced in the 1940s with African-American casts. These were made to appeal to an under-served market: the millions of black American moviegoers who otherwise would’ve had no chance to see people onscreen who looked like them. They played in the American Midwest, South and Southwest, mainly, on what was known as “the chitlin circuit,” an assortment of venues that could pass for movie theaters: churches, barns, nightclubs and other structures with walls wide enough for movie projection and enough floor space for a crowd.

Chitlin circuit movies are fascinating in their own right, but the representative snippets we see here are treated as stock footage, or the equivalent of a “historical recreation” that you might see in a History Channel documentary. Any innate artistic purposes they may have had is obliterated. Sometimes the filmmaker cuts them together with David Lynchian shots of the woods at night, leafless branches clawing at the sky. Meanwhile, an ominous and depressive and repetitive score churns.

I suppose you could make an argument that the chitlin circuit films connect with the story itself, in that they both reveal something about how race determines whether or not certain people’s voices get heard. But if that’s the point, it doesn’t come across. What’s onscreen here is often so very busy that “The Rape of Recy Taylor” turns into a parody of a certain mindset in American documentary filmmaking. There is a tendency among some directors to want to turn every new nonfiction feature into a dazzling visionary statement when it would’ve been perfectly OK to let the material be and find some way to explain to the audience why there are gaps or why certain parts feel a bit patched together.

There’s a section early in this movie that cuts together a witness’ testimony with bits of a chitlin circuit film and shots of the woods at night while, simultaneously, not one but two kinds of music play on the soundtrack: the original score and chopped-up bits of Dinah Washington’s classic performance of “This Bitter Earth,” use most memorably in Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep.” It’s as if an architect had decided to “help out” a single red rose by erecting a jumbled postmodern skyscraper around it. Let a rose be a rose.