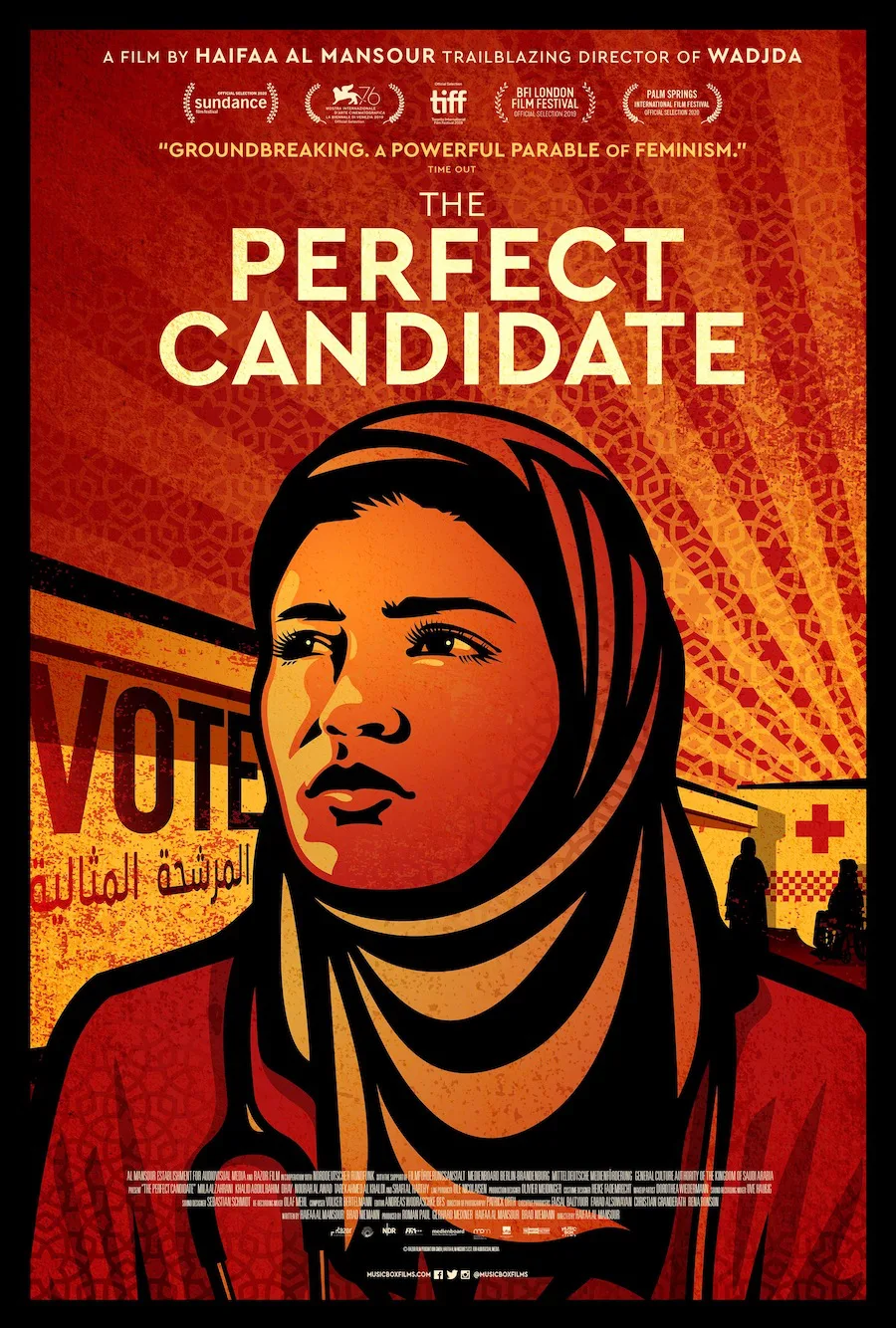

A lot has changed for Saudi women since writer/director Haifaa al-Mansour made her groundbreaking 2013 feature debut “Wadjda,” about a playfully headstrong Saudi girl who competes in a Koran contest, hoping to buy herself a bicycle with the winnings. From driving to the ability to appear in public with uncovered faces and further integrate into environments with male presence, new freedoms have trickled into their daily lives, the array of which al-Mansour portrays in “The Perfect Candidate” with care and some optimism. It’s an earnest, defiantly women-centric film that maintains a generally positive attitude about the future, albeit also one that feels a little less observational, a little more heavy-handed and prescriptive than the fiercely authentic “Wadjda.”

Though you can hardly blame al-Mansour for trying to advance the conversation by a little force, especially when Saudi women themselves are still living in a world where some of their countrymen would rather use their dying breath to spew hurtful misogyny, than say, offer their gratitude to a highly qualified female doctor trying to save their lives. And I am not really exaggerating or making assumptions here—this is pretty much the set up and framing of “The Perfect Candidate.” On one hand, we see welcome shots of women driving and enjoying their new, hard-earned liberties in the early moments of the film. But on the other, we follow the film’s protagonist Dr. Maryam Alsafan (an astonishingly resolute Mila Al Zahrani), a young and accomplished Saudi doctor, as she gets disrespectfully dismissed by an old male patient who refuses to even look at her, insisting that he’d rather trust a male nurse than a female doctor. One of Maryam’s male colleagues interferes with the disturbance, urging Maryam not to upset the patient. While his plea sounds more like a thoughtless piece of advice that suggests Maryam should pick her battles in a deeply patriarchal society, the doctor’s erasure still feels like a slap in the face on this side of the screen.

Through scenes of this nature designed to draw attention to what the Kingdom’s women are up against, al-Mansour—who reportedly had to direct “Wadjda” in a van away from men, but was able to integrate with her crew this time, thanks to loosening rules—uses Maryam as a catalyst for the kinds of progress she wants to see in her world. In one especially memorable sequence, we witness her crushing disappointment when she realizes that despite having friends and family members in high places, she wouldn’t be able to renew her expired travel permit and fly to Dubai for a medical conference. It’s a certification that can only be extended by the approval of her father, a sympathetic and supportive oud player, on the road to tour the country with his band. While the requirement for women to obtain a guardian’s permission to travel abroad has been lifted in 2019, the juxtaposition al-Mansour exposes in her film that’s set prior to this ruling is chilling—this is a world where roads mean freedom to men, but present nothing but obstacles to women.

Indeed, it is one such obstructive road that launches Maryam’s near-accidental political career. When her appeals to fix up the inaccessible dirt patch that leads to her hospital and delays patient care fall on deaf male ears, the young woman launches a movement of sorts and runs for the city council to take matters into her own hands against all the odds. The humor-filled and culturally rich scenes al-Mansour assembles around Maryam’s self-managed crusade are the film’s strongest segments. Through them, we get to navigate a society still unprepared to see women in positions of power as well as the intimate details of Maryam’s daily life at home, surrounded by her sisters Sara (Nora Al Awad) and Selma (Dhay), the latter being a wedding videographer who knows her way around social media. While Maryam’s campaign takes off in unexpected ways, al-Mansour intricately weaves in traditions and customs of a segregated society, honoring the resilience of women who manage to not only exist despite an array of men that deem them invisible, but also sharpen their pragmatic senses in order to thrive in a civilization made up of Kafka-esque bureaucracies invented to slow them down.

Sadly, “The Perfect Candidate” lacks a distinct visual grammar, feeling curiously less cinematic and minor when compared to the filmmaker’s assured efforts like “Wadjda” and “Mary Shelley.” But as a film that recognizes the giant strides small wins can make for women, it feels significant.

Now playing in theaters.