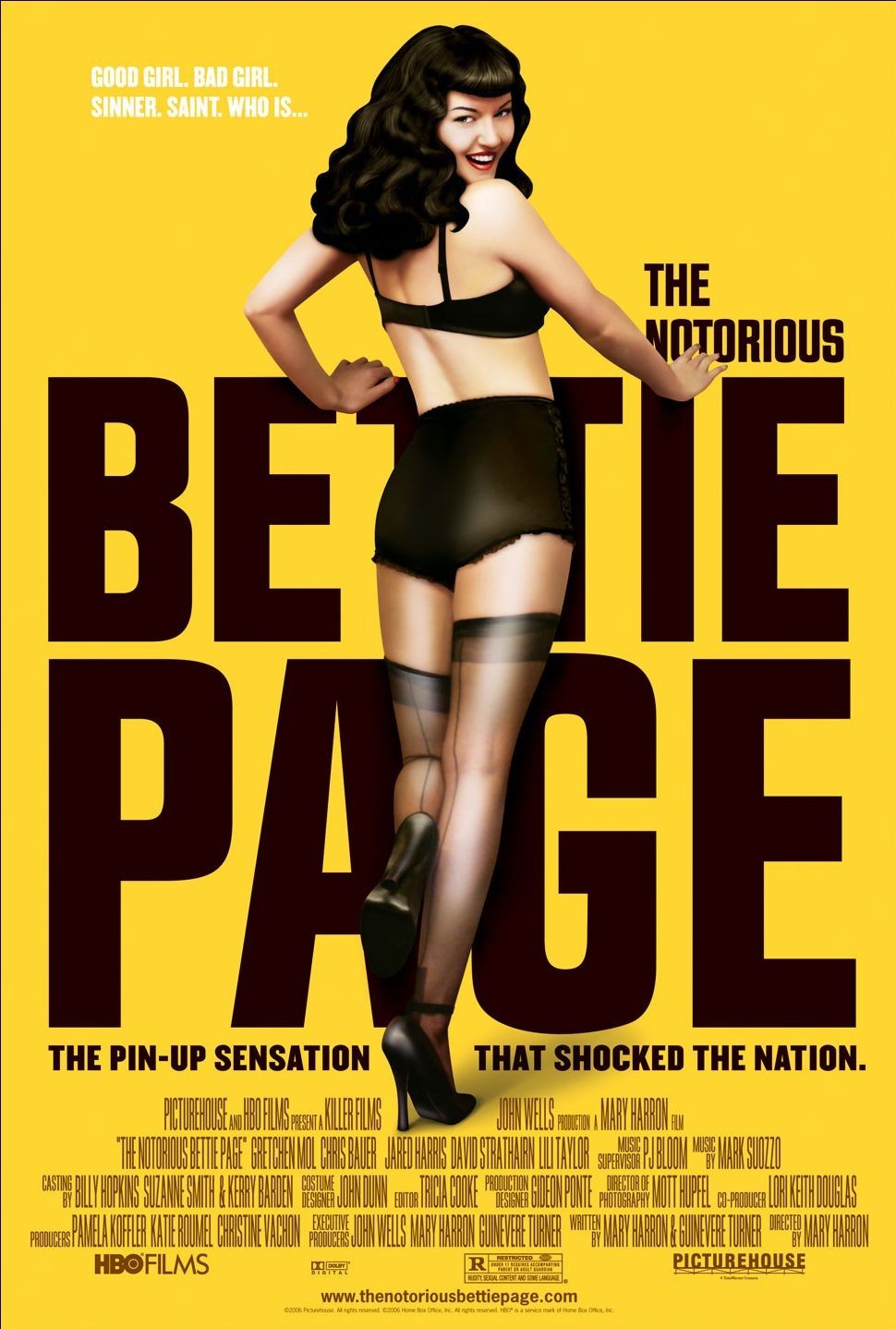

In the 1950s a pretty girl from Nashville named Bettie Page became the most famous model of her time — in certain circles. Marilyn Monroe followed a nude calendar photo into Hollywood stardom, but Bettie Page’s fame was within the specialist market of pin-ups and bondage photography. She was tied, trussed, handcuffed, chained and restrained while wearing high heels, nylons, garter belts, corsets and pointy brassieres, or nothing much at all, and yet her posing was so unaffected and her attitude so cheerful that she was like sunshine in the dark world of porn.

These things I know in a second-hand way because Page has been a cult figure for years, the subject of quasi-scholarly books and grainy videos. My friend Russ Meyer described her once as “the nicest girl you’d ever want to meet.” Now she is the subject of a curiously moving biopic, “The Notorious Bettie Page,” which is not very sexy or scandalous, nor is Bettie Page (Gretchen Mol) very notorious. “Celebrated” might have been a better word.

You might expect such a film would aim for scandal. Not at all. Nor is it an attack on censorship or prudery; it doesn’t defend Bettie and the pornographers she worked with, but presents them as mundane laborers in the world of sex, finding a market and supplying it. Most of Bettie’s bondage photos were taken by Irving Klaw, an unremarkable New Yorker who worked with his sister Paula. “Boots and shoes, shoes and boots,” Paula muses to Bettie. “They can’t get enough of them. Why? I guess it takes all kinds to make a world.”

Klaw was one of the targets of 1955 Senate hearings into pornography run by Sen. Estes Kefauver, and retired from the business. Bettie moved south to Miami and worked with the cheesecake photographer Bunny Yeager. Then she drifted out of modeling as casually as she drifted in, becoming a born-again Christian but never apologizing for her work, because if God created the female form, why would he be offended by its display?

I have here a 3-DVD set called “The Bettie Page Collection,” in which Bettie says the bondage work was pleasant because “we were always tied up by Paula, who was gentle and didn’t make the knots too tight.” Except for that time she was suspended from two trees. Bunny Yeager recalls that her most popular photos featured Bettie with two cheetahs, and we see both women posing with the animals, Bettie wearing a cheetah bikini. Yeager then provides a tour of her 100 most famous models, remembering something about every single woman, including one who sewed her own posing costumes.

I looked through Bettie Page’s photos and films hoping to find the same kinds of clues that must have inspired Mary Harron, who directed “The Notorious Bettie Page,” and Guinevere Turner, who wrote it with her. What I see is a pretty young woman with a spontaneous smile, who seems completely at home in whatever degree of nudity or distress. As Yeager famously said, “When she’s nude, she doesn’t seem naked.” The material doesn’t even come close to later notions of hardcore, and if there were men anywhere, I missed them on fast-forward. The bondage and spanking sessions are between playful women, in short loops with titles involving sorority initiations and bad girls. Sometimes you can clearly see that the spanking is pretend, with no actual contact.

So that is the real Bettie Page. Who is this woman created by Mol, Harron and Turner? It was Harron who starred Lili Taylor in “I Shot Andy Warhol” (1996), another film about the underside of fame. Here she sees Bettie Page as a young woman not so much naive as simply incapable of depravity; she glides through the porno scene as a grateful visitor having a good time. The film suggests that after being abused as a child and gang-raped as a teenager, Bettie found a friendly refuge in the smut mills of the Klaws; on her first visit to Irving’s studio she’s immediately offered a sandwich.

The tone of the movie is subdued and reflective. It does not defend pornography, but regards it (in its 1950s incarnation) with subdued nostalgia for a more innocent time. There is a kind of sadness in the movie as we reflect that most of these women and the men they inflamed are now dead; their lust is like an old forgotten song. Bettie Page is still alive in her 80s, and corresponds with some of her faithful fans, also in their 80s. Charlie Rose should invite Page and Yeager onto his program, lean across his table, and ask them to recall their days in flower.

In the Senate hearings held by Kefauver (David Straithairn), a father testifies that his son died while attempting something he may have learned from one of Klaw’s films. In the movies the witnesses at such hearings are routinely mocked as puritanical hypocrites, but Harron’s film feels sympathy for the father, and so do we. We also feel, on the other hand, that Irving and Paula Klaw were not so very evil, and the clients of their “photography studio” (usually professional men) are so awed by the opportunity to photograph naked women that they treat the models as goddesses.

Gretchen Mol is finally the key to the mysterious appeal of the film, to its sweetness and sadness. She plays a woman who for whatever reason does not consider her body an occasion for sin but a reason for celebration. In a haunting scene in an acting class (taught by Austin Pendleton), she is assigned to “do nothing” on the stage, and responds by absentmindedly beginning to remove her clothes. The way I read the scene, she was undressing in order to do nothing, because for Bettie Page to be dressed was to be doing something.