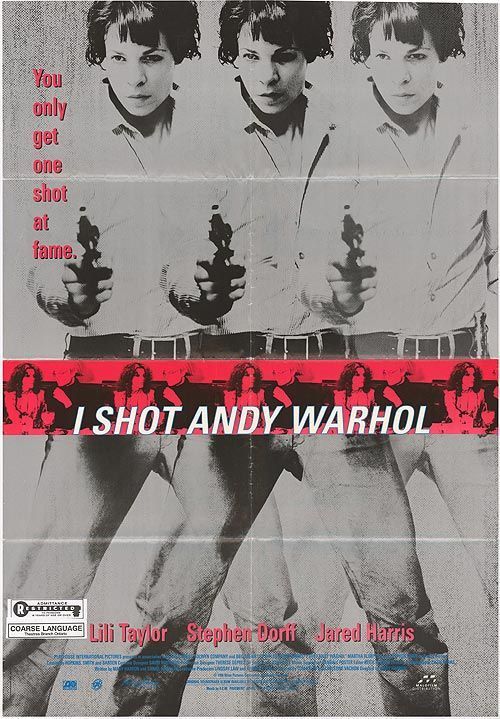

When Andy Warhol mused that in the future everyone would be famous for 15 minutes, he could not have anticipated that Valerie Solanas would earn her fame by shooting him. To be fair, she did it only as a last resort; God knows she tried everything else to get Andy to make her famous. Now her life and crime are dramatized in “I Shot Andy Warhol,” which Warhol might have found the perfect movie title, combining as it does the deadpan, the sensational, and name-dropping.

Solanas walked into the Factory, Warhol’s studio, on June 3, 1968, pulled out a gun that was given to her by a guy she met in a mimeo shop, and fired on America’s most famous artist. “Jesus Christ, now she’s shot somebody,” one of Warhol’s assistants says. (One expects Warhol to summon his strength and gasp, “Not just somebody.”) When the police ask her why she did it, she says she has “a lot of real involved reasons.” She sure does.

In following the life of Valerie Solanas from her wounded childhood to her moment of vindication, director Mary Harron and actress Lili Taylor go inside the mind of a woman who was deranged and possibly schizophrenic, and follow the logic of her situation as she sees it, until her act is revealed as the inevitable result of what went before.

Solanas, who was abused as a child and worked her way through college as a prostitute, comes across as a gifted woman who never quite loses a wry sense of humor. After a short career on her college paper (she writes columns arguing that females can reproduce without males and should do so), Valerie takes on Manhattan; she writes plays, does readings in luncheonettes, and is befriended by Candy Darling (Stephen Dorff), a transsexual who takes her for the first time to the Factory.

Warhol (Jared Harris) finds her as interesting as he finds anything. He puts her in one of his movies (“I, a Man”), and she emotes on a staircase of the Chelsea Hotel–too hot for Warhol’s cool. She writes a play and hopes Warhol will produce it, but her precious typed playscript is tossed behind a sofa at the Factory, and when no one will return it to her, Solanas begins to get angry.

At this point she is essentially a bag lady, living and writing on the roof of a building, and supporting herself by prostitution and by selling copies of her radical lesbian feminist polemic, The S.C.U.M. Manifesto. The initials stand for “The Society for Cutting Up Men.” Her friends, including a sometime lover named Stevie (Martha Plimpton) try to help her, but no one in this self-obsessed world really sees her, listens to her, and cares.

Harron, a first-time director who co-wrote the screenplay with Daniel Minahan, does two remarkable things in her movie: She makes Solanas almost sympathetic and sometimes moving and funny, and she creates a portrait of the Factory that’s devastating and convincing. Warhol emerges as a man whose entire being–intelligence, sexuality, artistry–seems concentrated in his detached, bemused gaze. (If Andy ever got a tattoo, I hope it read, “I like to watch.”) He fears personal contact; he snaps pictures and makes tapes of the people around him, and I imagine him later, alone, arranging those documents as an entomologist might pin butterflies to a corkboard.

Solanas, on the other hand, is passionately engaged in her life. She says she hates men, but depends on two to make her famous: Warhol, and Maurice Girodias (Lothaire Bluteau), the Olympia Press publisher who prospered in the 1950s and ’60s by publishing pornography with literary pretensions, and literature with pornographic pretensions. (His list ranged from Lolita and The Ginger Man to Harriet Marwood, Governess.) Of all the literary dinners ever shared by authors and their publishers, the encounter between Solanas and Girodias must rank as the most unlikely. Solanas wanted a publisher for her manifesto; Girodias wanted to find a new trend to ride, now that porn was becoming commonplace. Desperately poor, Solanas signed a contract that gave her an immediate cash payment, and then became obsessed with the (correct) notion that Girodias planned to steal her work for a pittance.

Everywhere she looked, more presentable feminists seemed to be taking her ideas and running with them. Watching bra-burners on TV, Valerie complains, “They got their message from me.” She bombards the Factory for the return of her play. Brushed off by Warhol, told by Candy Darling that she’s been “excommunicated,” Solanas walks into the Factory and starts shooting.

Lili Taylor plays Solanas as mad but not precisely irrational. She gives the character spunk, irony and a certain heroic courage (the sight of her typing on her rooftop, the wind rustling the pages of her manuscript, is touching). Variety calls Taylor “the first lady of the indie cinema,” and in one independent film after another (“Mystic Pizza,” “Dogfight,” “Household Saints,” “Arizona Dream,” “Bright Angel,” “Short Cuts”) she has proven herself the most intelligent and versatile of performers. If you had to look at all of the films of one actor who has emerged in the last 10 years, you would run less chance of being bored with Lili Taylor than anyone else.

Some audience members, I’m sure, will not be in sympathy with “I Shot Andy Warhol.” They will find it the story of a pathetic madwoman who shot an emotional eunuch. And so it is. But not any madwoman, and not any eunuch, and that is the gift art can bestow: to show us the person beneath the skin, and to reveal that even the strangest behavior is often simply a strategy for obtaining what we all require, love and recognition.