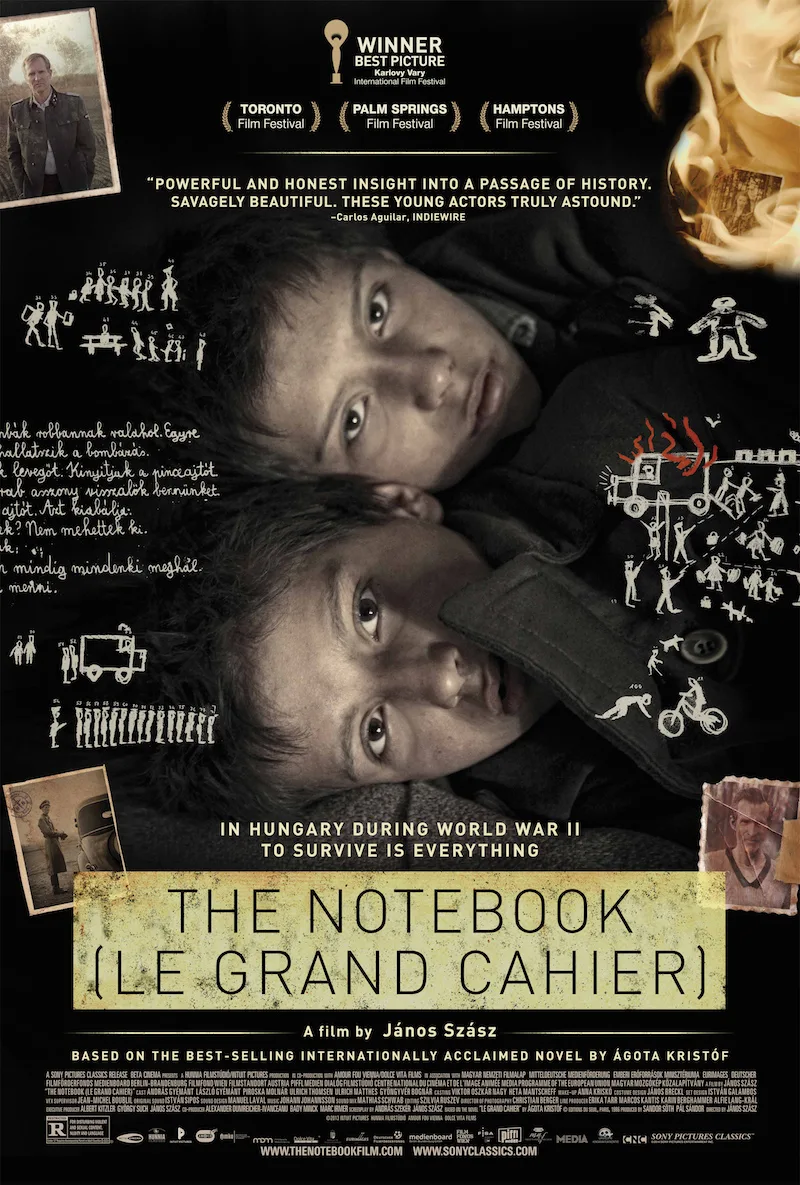

Telling of 13-year-old twin boys (László Gyémánt and András Gyémánt) who endure the harsh punishments of World War II’s final stretch in rural Hungary, János Szász’s “The Notebook” is a well-crafted but otherwise undistinguished and tedious entry in a long line of European films that make a grotesque show of war’s horrors, often viewed through the lens of childhood’s disabused innocence. Such films, whatever their quality, so often end up in U.S. art houses and the Oscars’ Best Foreign Film sweepstakes, it’s tempting to suspect there’s a single factory stamping them out according to formula.

The most novel thing about “The Notebook” (not to be confused with the Ryan Gosling vehicle of the same title) is how lumpy, labored and relentlessly episodic its narrative is. If one went into it knowing nothing of its origins, the film’s lack of dramatic structure might suggest a singularly inept screenwriting exercise that somehow made it into production. In fact, it’s close to impossible to imagine this movie being made had it been based on an original screenplay rather than a well-regarded novel, “Le Grand Cahier,” by Agota Kristof, a Hungarian who writes in French.

Published in 1986 and obviously descended from “The Tin Drum,” “The Painted Bird” and the like, Kristof’s tale (here scripted by her, Szász and András Szekér) explores the not altogether novel idea of war’s brutalizing effects by focusing not on its military center but the civilian periphery. Once air raids have made city life too perilous, the twins’ mother (Gyöngyvér Bognár) takes them to the countryside and deposits them with their grandmother (Piroska Molnar), an abusive alcoholic known to locals as “the Witch.” Granny will make sure that, for the boys, war will be hell on the home front too.

With both of their parents having disappeared in different directions, the twins react to their harsh new circumstances with an orgy of purposeful masochism. Deciding they must toughen themselves up to meet the cruelties that are surely coming, they starve themselves and attack their bodies in various ways, including cutting themselves with a knife and pouring alcohol over the wounds.

There’s an emotional component to this Spartan regimen too. Seeking to quench all weakness in themselves, the boys read the Bible’s accounts of ancient brutalization and, obeying a command from their father, begin to keep a notebook recording the war’s hardships as unsentimentally as possible. This notebook almost surely is a device more suitable to a novel than a film, where it seems both extraneous and contrived.

After establishing the twins’ campaign of self-discipline, which occupies the tale’s initial section, the film’s narrative often feels shambling and aleatory, centered less on the boys’ development than on their encounters with random people who seem like they might have been drawn from a novelists’ database of stock characters, WWII division.

There’s an epicene Nazi officer (Ulrich Thomsen) who is of course a pedophile. There’s a neighbor girl with a hairlip (Orsolya Toth), who predictably mutates from taunting enemy to fast friend. There’s a friendly Jewish craftsman, a corrupt priest and a pro-Nazi young woman who strips the boys, takes them into her bath and masturbates using their feet—the kind of soft kink that’s all but inevitable in a genre that’s built on various sorts of vicarious prurience.

No less standard, there’s a passing invocation of the Holocaust, which takes the form of a scene almost identical to one in last year’s “The Book Thief,” an equally bad but far glossier film: Scores of bedraggled, sad-eyed Jews being shepherded down a village street toward their inescapable doom.

One reason all this adds up to so little is that the twins are flat and uninteresting characters to begin with and they don’t grow as the story unfolds. Ditto for Granny and the other secondary characters. Another problem is that certain incidents in the film are downright unbelievable or risible. These range from a grave that is dug in hard ground in what seems like minutes to a claim that a girl who dies from being raped by marauding soldiers “at least died happy.” Really?

Finally, an objection about what happens to the brothers at the end of the film, which I won’t reveal except to say it seems to contradict very basic things we’ve been told about them earlier. Coming out of a screening of the film, this reviewer encountered a group of folks complaining that the ending “makes no sense.” One, however, opined that it was perhaps “symbolic,” which would seem to be the case. Kristof’s novel is actually the first volume of a trilogy in which the two subsequent volumes trace the contrasting fates of the brothers in the post-war period. So the gambit, which sets up the story’s next stages, may have a kind of justifiability as a literary conceit. Yet it flies against the fundamental realism of film, where it’s always a sin to sacrifice common-sense believability and character consistency to high-flown rhetorical “symbolism.”