Has there ever been a time in human history better equipped to achieve global healing through the guidance of meditation? We’re spending the majority of our days confined to our homes not because we are antisocial, but because we now have a heightened awareness of how our choices impact our neighbors next door and around the world. As Sharon Salzberg, co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society, observes in Robert Beemer’s documentary, “The Mindfulness Movement,” the therapeutic techniques she prescribes bring each of us a profound knowledge “that our lives have something to do with one another, and the indication of that is that everybody counts and everybody matters.” I fully endorse the message blatantly expressed by Beemer’s picture, but as a work of cinema, it drove me nuts in how its style was antithetical to the principles its numerous subjects were championing.

The first red flag occurs early on, as a title card informs us that we are entering the first chapter of Jewel’s Journey, detailing how Jewel Kilcher’s rise from homeless youth to successful singer/songwriter was enhanced by her achieving an inner peace about her present experience—in others words, mindfulness. After breezing far too quickly through Jewel’s story, which joins her talking head interview with grainy recreations of a faceless girl wandering the streets of San Diego, we suddenly jump ahead to Chapter One of Dan Harris’ story about having a panic attack on live television after “self-medicating” with cocaine and ecstasy. Then we’re tossed into Chapter One of George Mumford’s life story, one that he barely has time to discuss (his promising basketball career was cut short by an injury, leading him to get hooked on pain medication) before the film cuts to the first chapter of Salzberg’s story. Had the film been comprised solely of these four parallel narrative threads, juxtaposing how each person’s life was profoundly transformed by meditation, resulting in Harris devising the popular Ten Percent Happier franchise (complete with a book, podcast and app) and Mumford teaching the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers mindfulness (ultimately leading both teams to multiple world championships), Beemer might’ve had something special here.

Instead, the picture intends on cramming in as many vignettes illustrating the full extent of the nationwide movement regarding mindfulness that can possibly fit into its 100-minute running time, resulting in a glib and repetitive informercial that pulls off the tricky feat of simultaneously feeling too short and interminable. The main title card doesn’t even turn up until the 11-minute mark, since the four “Chapter One” segments are followed by a second prologue about the movement itself that sounds as if it were narrated by Tilda Swinton’s lucid dream-peddling representative in “Vanilla Sky.” Rather than give us an intimate understanding of the frustrations voiced by people like Salzberg as they work to turn their self-judgement into compassion, the film is filled wall-to-wall with smiling extras dubbed “bliss faces” by the editors of a print magazine entitled Mindful. They tell Beemer that they are against the use of such sickly imagery—the kind we’re used to seeing on drug commercials to distract us from the horrifying list of side effects—since it dilutes the grit and pain that is also experienced on one’s journey toward inner enlightenment. If only the filmmakers had gotten the memo.

For a documentary espousing how meditation can expand the capacity of one’s imagination, “The Mindfulness Movement” demonstrates an egregious lack of creativity. Louis Schwartzberg’s “Fantastic Fungi” found ingenious ways of visualizing the exhilaration felt by its subjects when under the influence of medicinal mushrooms, whereas Beemer’s method for showing how meditation rewires and restructures the brain is to film bleary diagrams on a subject’s computer screen. It’s as if the director and his team forgot that watching a film can be an enormously enriching form of meditation, and that it is their job to center our focus long enough to make each moment breathe and resonate. Not only is the film structured as a constant series of disruptions, complete with stress-inducing news footage, every scene is intruded upon by an insulting score that never wastes a chance to tell us how to feel, or in some cases, what we’re seeing (a segment on the Mindful Warrior Project aiding veterans with PTSD is accompanied by a generically militaristic drum beat). After a while, I started feeling like Peter Graves in “Airplane!” when he found himself demonstrating the various signs of food poisoning as they’re listed by Leslie Nielsen. With every successive sequence warning about the symptoms of avoiding meditation—restlessness, agitation, a wandering mind, etc.—I became so restless, agitated and distracted that I simply wanted to close my eyes. Then the film instructed me to do precisely that during two minute-long meditation demos, which was a welcome reprieve, though it proved even harder to keep my eyes open after that.

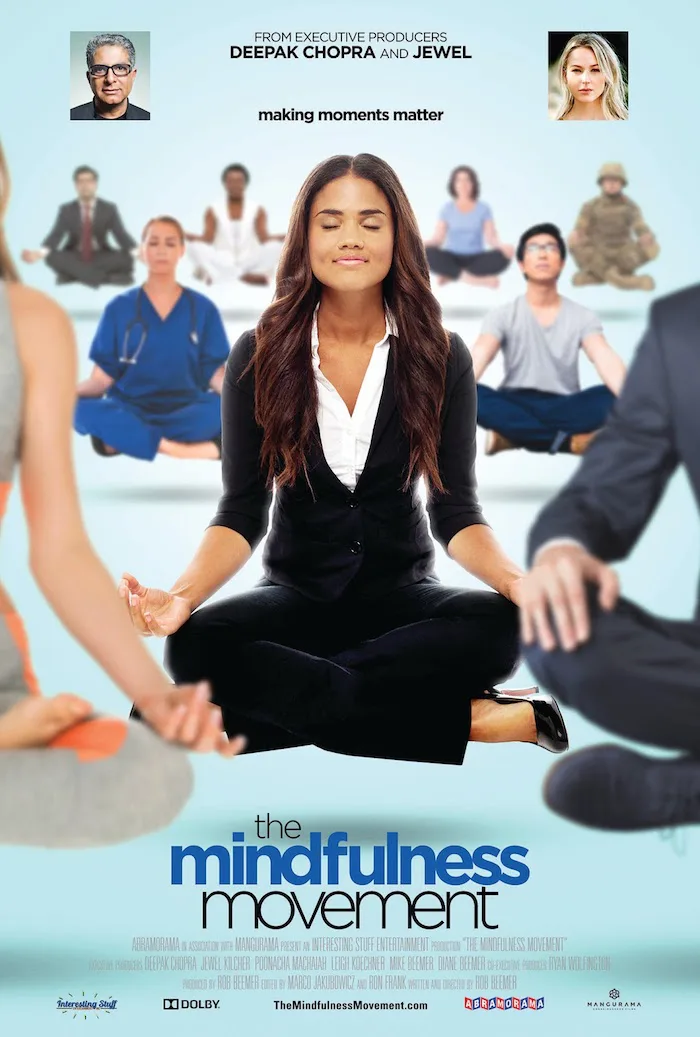

What’s most problematic about “The Mindfulness Movement” is that it is more concerned with plugging the various programs implementing meditation—in schools, prisons, hospitals, police stations, corporations, halls of government—than it is in doing any of them justice by granting each segment the necessary attention and emotional depth. At one point, Deepak Chopra, who served as an executive producer, is seen plugging the film we’re watching, which is available for purchase on the website tagged at the end. The best thing that I can say about this missed opportunity is that it did cause me to reflect on how mindfulness changed my life without me even realizing it when I was an insecure teenager. After a junior high spent largely in isolation, I found acceptance and friendship in my high school’s drama club, where our director would guide us through meditations before every one of our plays, accompanying her words with the music of Enya. We’d float on a cloud that landed in a field, where we’d walk to a brook and touch our reflection, changing our face into that of our character. The exercise left us feeling deeply connected with one another and with the parts of ourselves we would typically suppress. Meditation could potentially emerge as one of the definitive remedies of our time, and it is sorely deserving of a better cinematic analysis than this bliss-faced bore.

Premieres on VOD today, 4/10.