Luc Besson’s “The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc” labors under the misapprehension that Joan’s life is a war story and takes place largely on battlefields. In fact, it takes place almost entirely within the consciences of everyone involved. The movie does at least concede that a good part of Joan’s legend involves her trial for heresy and her burning at the stake, and these scenes may prove educational for the test audience members who wrote on their sneak preview cards, “Why does she have to die at the end?” Two of the best films ever made are about Joan of Arc: “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” by Carl Dreyer (1928), and “The Trial of Joan of Arc,” by Robert Bresson (1962). One of the worst, “Saint Joan” (1957), by Otto Preminger, had in common with Luc Besson’s movie the theory that Joan must look like a babe. Dreyer’s Joan was Falconetti, a French actress whose haunted face mirrored one of the greatest performances in cinema–the only one she ever gave. Preminger’s was Jean Seberg, found in Iowa after an international talent search. The search for her talent continued after the film was completed, and it was finally found in Godard’s “Breathless” two years later.

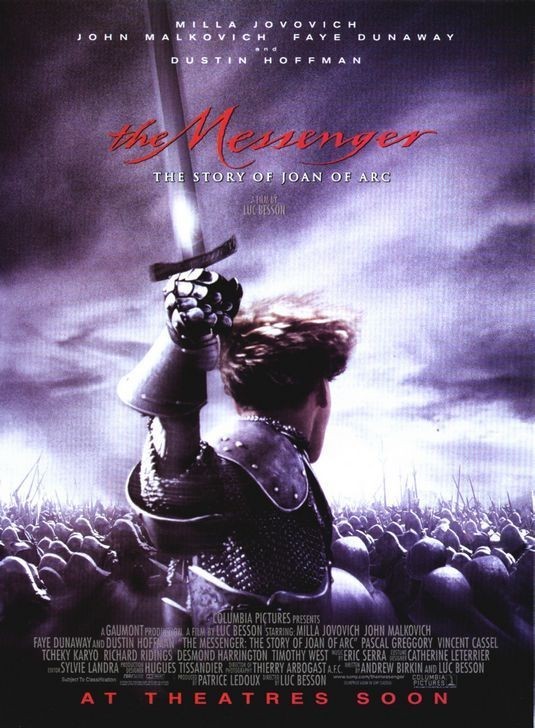

Besson has cast Milla Jovovich as his Joan. She was his wife at the time they started shooting. They have since split–although he says they would still be together if they could only have made movies 365 days a year, a statement that may provide more insight than he intended. Jovovich, who also starred in Besson’s “The Fifth Element,” is a healthy, cheerful, open-faced 24-year-old actress who seems much too robust and uncomplicated to play Joan.

The movie is a mess: a gassy costume epic with nobody at the center. So deficient is Besson at suggesting the conscience which rules Joan’s actions that the movie even uses another character, the Grand Inquisitor, as a surrogate conscience, and brings in Dustin Hoffman to play it. That Hoffman’s performance is the best in the film should have been a nudge to the filmmaker that he could cut back on the extras and the battle scenes and make the movie about–well, about Joan.

Joan of Arc was a naive young French peasant woman, illiterate, who was told by voices that she must go to the aid of her king. France at that time was ill-supplied with kings; the best it could offer was the reluctant Dauphin (John Malkovich), later Charles VII. She informed him her destiny was to lead French troops on the battlefield against the English, who were godless (or foreign, which to the French was a negligible distinction).

Legend has it she ended the siege of Orleans. Legend may be wrong. A new book published in France by the historian Roger Caratini claims “precious little of what we French have been taught in school about Joan of Arc is true.” He finds scant evidence that Joan did much more than go along for the ride and adds cruelly that she could not have raised the siege of Orleans because the city was never besieged in the first place. Her trial for heresy was not at the hands of the British but under the French Inquisition at the University of Paris, and her greatest crime may have been dressing like a boy and offending the ecclesiastical gender police. Her legend was “more or less invented” in the 19th century, we learn, as a tonic for emerging French nationalism, which had a “desperate need for a patriotic mascot.” Of course we do not expect “The Messenger” to be a revisionist downgrading of the French national heroine, who was burned by a schismatic branch of the church and canonized by Rome five centuries later without having, perhaps, done much to deserve either. We expect a patriotic epic, in which the heroic young woman saves her country but is destroyed by an effete ruler and a lot of grim old clerics. Even if the film is not about a battle of opposing moralities, even if it is not about conscience (as the Dreyer and Bresson films are), it can at least be as much fun as, say, “Braveheart,” wouldn’t you think? No such luck. Besson’s film is a thin, uninvolving historical romp in which the only juicy parts are played by supporting characters, such as the Dauphin, made by John Malkovich into a man whose interest in the crown essentially ends with whether it fits. Faye Dunaway has fun as his stepmother, Yolande D’Aragon, who schemes against Joan as any mother would when her son falls under the sway of a girl from the wrong side of the class divide. And Dustin Hoffman is really very good as the Inquisitor, even if his role seems inspired by the desperate need to somehow shoehorn philosophy into the film. I was reminded of the Roger Corman horror picture where holes in the plot were plugged by hiring two bit players and having one ask the other, “Now explain what all this means.”