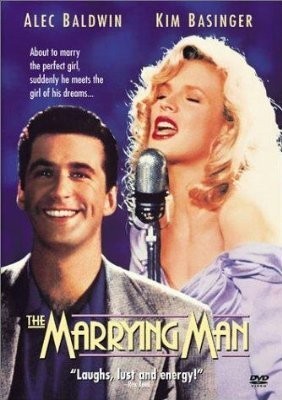

They say “The Marrying Man” is based on a true story, involving the relationship of shoe tycoon Harry Karl and actress Marie (The Body) McDonald, two of the more colorful characters on the L.A.-Vegas circuit, circa 1950. They were married to each other four times, it is said, even though she meanwhile carried on with mobster Bugsy Siegel. When Neil Simon heard the story he knew he had the makings of a comedy. What he didn’t know is that the chemistry between his stars, Kim Basinger and Alec Baldwin, would make Karl and McDonald look like Ozzie and Harriet.

The saga of the filming of “The Marrying Man” is by now well known, having been chronicled in a steamy article in Premiere magazine, which was of course denied by the agents of the stars. The magazine reported that Baldwin and Basinger fell deeply and passionately into love and lust, and that the filming of many a scene was delayed while they lingered in their mobile homes. They were still holding hands when I saw them on Oscar night, so maybe there’s truth here somewhere.

What cannot be denied is that they have chemistry on the screen. “The Marrying Man” is not a great comedy but it is a living, breathing one that overcomes any problems connected with its filming to deliver a genuinely randy and scandalous love story, about two people who cannot live without one another, but keep trying to, anyway. There’s more juice in the story than I usually expect from Neil Simon; the characters don’t just trade one-liners, but get under each other’s skins.

Baldwin plays Charley Pearl, a sleek, young Hollywood millionaire who is engaged to the daughter (Elisabeth Shue) of a hot-headed studio chief (Robert Loggia). On the eve of his wedding, he goes to Vegas for a bachelor party, and in a sleazy gambling den outside of town he lays eyes, and soon everything else, on a sexy chanteuse named Vicki Anderson (Basinger). She describes herself as the property of Siegel (Armand Assante), and although Baldwin realizes it is certain death to flirt with the mobster’s girl, he crawls in her bedroom window nevertheless, and is cornered in flagrante delicto by Bugsy and his boys.

Bugsy is capable of surprises. Instead of ordering the execution of the two lovers, he orders them to be married (“I was about to dump her anyway”), and so they are, in a funny scene in one of those Vegas instant-wedding chapels. What they soon discover is that they’re more in love with danger than with each other, and that leads to their first split.

But Baldwin is obsessed. So is Basinger. The movie is about lust, not love; about people who drive each other crazy, and can’t help it. All of the rest of Simon’s plot, energetically directed by Jerry Rees, is at the service of that fact. And the story is planted in a rich 1940s period atmosphere: the cars, the neon, the cigarettes, the Brilliantine on the hair.

Simon, who has been around show business a long time, supplies his playboy with four buddies who are constantly getting him out of trouble, and according to the press notes these buddies are inspired by the young Sammy Cahn, Phil Silvers, Tony Martin and Leo Durocher. They’re standard wisecracking Simon supporting players, but a couple of the smaller roles are filled with real presence. Armand Assante, who looks and sounds different in every movie, is a sardonic and intelligent Bugsy Siegel, and Robert Loggia, as the studio boss, develops a towering rage that is impressive to behold. He screams so loudly you can’t understand half the words, but you get the idea.

“The Marrying Man” is like those lightweight, atmospheric comedies of the postwar era, in which the chemistry between the stars covered up for a certain lack of logic, continuity and polish. The movie has rough edges and a slapdash air about it, but somehow it works, perhaps because Basinger and Baldwin throw themselves with such abandon into their roles.

Chemistry is a strange phenomenon. Many critics found it lack ing between Sean Connery and Michelle Pfeiffer in “The Russia House,” and between Robert Redford and Lena Olin in “Havana.” Both of those movies were made with far greater subtlety and skill than a humble item like “The Marrying Man,” but hardly anyone, I think, is likely to complain about the chemistry.