`The Long Walk Home” tells the stories of two women and their families at a critical turning point in American history. One of the women is black, a maid in an affluent neighborhood, a hard-working woman who goes home after a long day and does all of the same jobs all over again for her family. The other woman is white, the wife of a successful businessman. She works, too. She doesn’t have a paid job, but in 1955 in Montgomery, Ala., it was full-time work to please a husband who thought a woman’s place was in the home, and who had a great many other thoughts on the proper places of just about everybody in his narrow world.

These characters are confronted by a historic moment. One day in Montgomery a black woman named Rosa Parks, who had worked hard and was tired, refused to stand up in the back of the segregated bus when there was an empty seat in the front. Her action, born out of a long weariness with the countless injustices of discrimination, inspired the Montgomery bus boycott, which was led by a young local preacher named Martin Luther King Jr., and which grew into the civil rights movement.

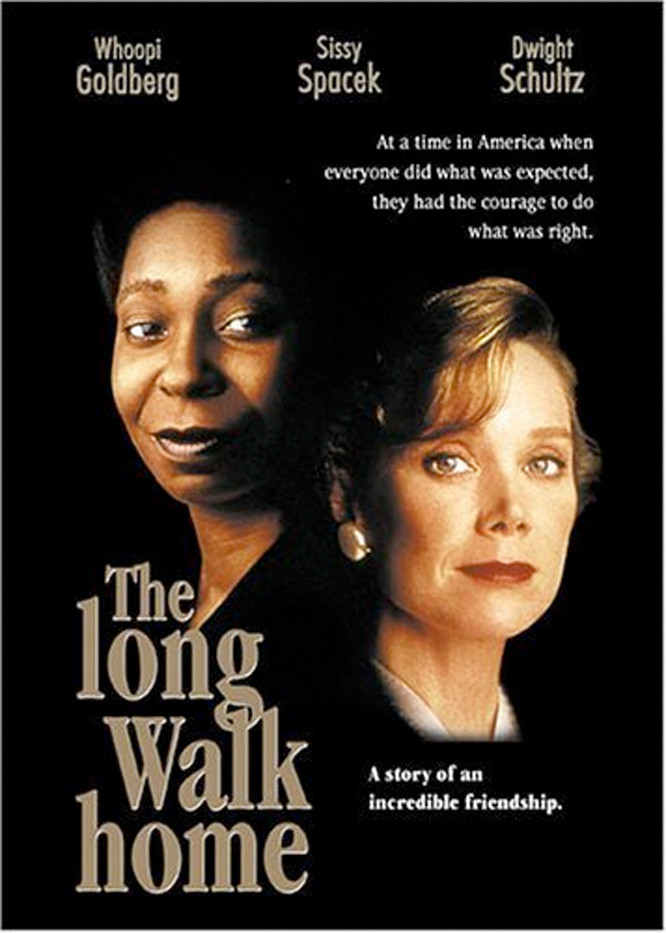

For a woman like Odessa Cotter (Whoopi Goldberg), however, the eventual verdict of history could not have been easily guessed on the day she decided to join thousands of other Montgomery blacks in refusing to take the bus. She simply knew how she felt, and acted on it, and started to walk to work every day. That meant getting up a couple of hours earlier in the morning, and getting home long after dark at night, and it meant blisters on her heels. It also meant inconvenience for her employer, Miriam Thompson (Sissy Spacek), who had a house to keep and a husband to feed, and who took her duties as a wife very solemnly – suppressing the obvious reality that she was married to a jerk.

Odessa is not eager for her employer to discover she is honoring the boycott – she doesn’t want to risk losing her job – but one day Miriam finds out, and decides that she will give the maid a ride in her car a couple of days a week. This decision of course would enrage Miriam’s husband, a self-satisfied bigot named Norman (Dwight Schultz), but Miriam doesn’t tell him, and when he finds out, she defends her action as part of her job as a dutiful housewife.

In the meantime, she and her husband grow in different ways because of the boycott. Miriam is no activist, but can see as a wife and a mother what the boycotting black women are going through, and begins to sympathize with them. Her husband is taken by a relative to a White Citizen’s Council meeting, where rabble-rousers depict the boycotters as dangerous subver sives (any true American would of course prefer to stand in the back of the bus than sit in the front – if he were black, that is).

The movie leads up to an inevitable confrontation between the white husband and wife, and to a climax of surprising power. But the general lines of the plot are not what make the movie special. We know going in more or less what will happen, both with the boycott and with these characters. What involved me was the way John Cork’s screenplay did not simply paint the two women as emblems of a cause, but saw them as particular individuals who defined themselves largely through their roles as wives and mothers.

This movie would not have been made quite the same way 10 or 20 years ago. The focus would have been on the liberalism of the white woman and the courage of the black woman, and most of the scenes would have involved the white family. “The Long Walk Home” takes the time to develop both families, to show that in addition to being heroic but abstract media images, the maids like Odessa were also individuals with all the usual human hopes and worries, not least of which was losing a job.

Because the movie does center some of its important scenes inside the black household, it’s all the more surprising that it uses the gratuitous touch of a white “narrator” – apparently to reassure white audiences the movie is “really” intended for them. The narrator is Spacek’s teenage daughter, who has no role of any importance in the movie and whose narration adds nothing except an unnecessary point of view. When she talks about her memories of “my mother,” we want to know why Goldberg’s daughter doesn’t have equal time. She probably has more interesting memories.

That objection aside, “The Long Walk Home” is a powerful and affecting film, so well played by Goldberg and Spacek that we understand not just the politics of the time but the emotions as well. In a way, this movie takes up where “Driving Miss Daisy” leaves off. Both are about affluent white Southern women who pride themselves on their humanitarian impulses, but who are brought to a greater understanding of racial discrimination – gently, tactfully and firmly – by their black employees.

Miss Daisy and Miss Miriam are not revolutionaries. Neither are Hoke Colburn and Odessa Cotter. But the situation had gotten to the point where something had to be done, because people after all must be permitted fairness and dignity, and these two movies tell two small and not earthshaking stories about ordinary people, black and white, who managed to talk and managed to listen, and made things a little better.