A handsomely mounted, never-less-than conspicuously intelligent but ultimately too-conventional historical drama, “The Liberator” shoehorns the epic life of early 19th-century South American revolutionary Simón Bolivar into two hours of intermittently powerful cinema.

The movie’s opening sequence gives the viewer all the movie’s strengths and weaknesses in sketch form. On a dark night, a powerful man enters a guarded manse; the camera follows him from behind. A title tells the viewers that it’s 1828. The man hands his sword to one aide; hands a piece of laundry to a maid. Messages are delivered. Brief conversations are held, in Spanish and English. The man, an important military and political figure, finally gets to the room he’s looking for. A woman waits for him there. “Now I’ve got you,” the woman says, and the couple begins a clinch. But wait. The house is suddenly under siege. The man—yes, it’s Simón Bolivar—must leap from a window to escape. He tries to take the woman with him. “They’re not here for me,” she protests. Out he goes. The torrential rain begins, as does a flashback that’s intercut with the immediate action: young Simon coping with the death of a parent, fleeing to the arms of a slave on his estate. Now adult Bolivar runs, as the music, by Gustavo Dudamel, grows more lushly urgent and heroic, and a man on horseback says of Bolivar, “He must die tonight.”

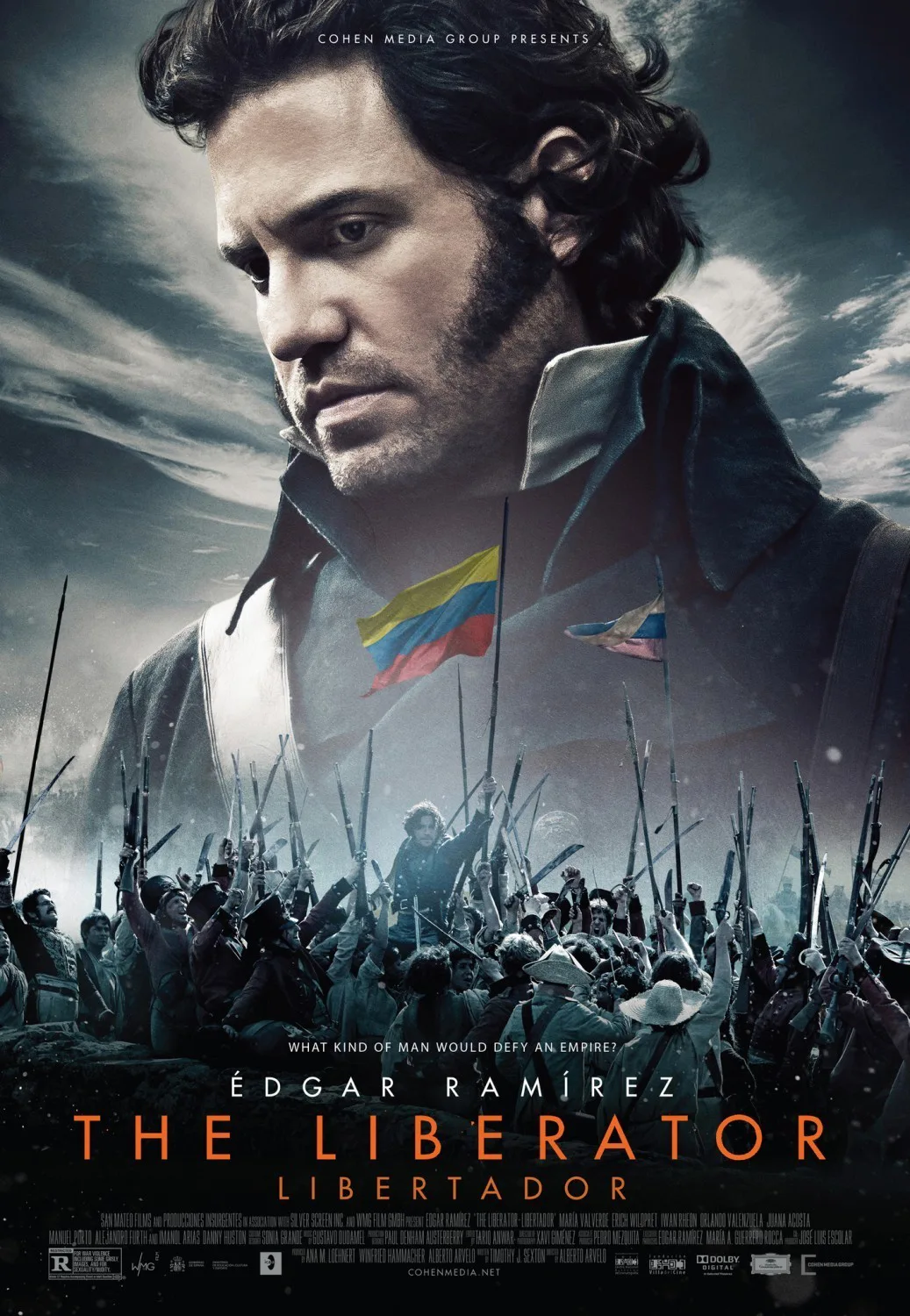

Does he? Will he? Well, the movie then flashes further back, depicting young man Bolivar in Spain, where he beats Prince Ferdinand at badminton, and the Prince doesn’t take it well. (That’s what they call foreshadowing, as the Prince will someday become the King that Bolivar leads his rebels against.) Bolivar also finds the first love of his life at this affair, and brings her back to Venezuela to wed him. The movie’s first half-hour sees Bolivar as more a lover than fighter, and the stolid, oak-like physicality Edgar Ramirez brings to the role contrasts well with the delicacy of Maria Valverde. (Ramirez, readers may recall, played a rather more malevolent manifestation of radicalism in Olivier Assayas’ epic “Carlos” a few years back.) Unhappy circumstances, though, soon find Bolivar leading a dissolute life in Paris, with his former tutor accusing him of selling out. A fortuitous meeting with Martin Torkington, a British banker of muddy motives (played with a nice approximation of Old Old World smarm by Danny Huston) helps set Bolivar on the path to revolutionary action in his home country, and a dream of an independent, united South America.

Anyone with a map of that continent knows that Bolivar was unable to achieve that aim, although he is nevertheless still called “The Liberator” throughout South America to this day. Writer Timothy J. Sexton, director Alberto Arvelo and actor/executive producer Ramírez have done due diligence to insure that their liberator is a creature of more than just charisma and bravery; he’s thoughtful to a fault, and his biggest character flaw as depicted here is that he’s too fair-minded to act with the ruthlessness necessary to get what he wants. Bolivar’s story, which is replete with setbacks, exile, and other complications, sometimes feels rushed by this movie. The scene in which the Liberator’s largely unarmed army of diverse freedom fighters (the movie is scrupulous in depicting many persons of color and women as among their number) practically sacrifices itself en masse in order to wrest the strategically crucial city of Bogota from the Spanish is a spectacularly played scene both dramatically and cinematically, but Arvelo can’t spare the time to make its implications more deeply felt. I know, I know—it sounds as if I’m complaining that the movie is too short. Perhaps it is.