Christianity teaches that Jesus was both God and man. That he could be both at once is the central mystery of the Christian faith, and the subject of “The Last Temptation of Christ.” To be fully man, Jesus would have had to possess all of the weakness of man, to be prey to all of the temptations–for as man, he would have possessed God’s most troublesome gift, free will. As the son of God, he would of course have inspired the most desperate wiles of Satan, and this is a film about how he experienced temptation and conquered it.

That, in itself, makes “The Last Temptation of Christ” sound like a serious and devout film, which it is. The astonishing controversy that has raged around this film is primarily the work of fundamentalists who have their own view of Christ and are offended by a film that they feel questions his divinity. But in the father’s house are many mansions, and there is more than one way to consider the story of Christ–why else are there four Gospels? Among those who do not already have rigid views on the subject, this film is likely to inspire more serious thought on the nature of Jesus than any other ever made.

That is the irony about the attempts to suppress this film; it is a sincere, thoughtful investigation of the subject, made as a collaboration between the two American filmmakers who have been personally most attracted to serious films about sin, guilt and redemption. Martin Scorsese, the director, has made more than half of his films about battles in the souls of his characters between grace and sin. Paul Schrader, the screenwriter, has written Scorsese’s best films (“Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull“) and directed his own films about men torn between their beliefs and their passions (“Hardcore,” with George C. Scott as a fundamentalist whose daughter plunges into the carnal underworld, and “Mishima,” about the Japanese writer who killed himself as a demonstration of his fanatic belief in tradition).

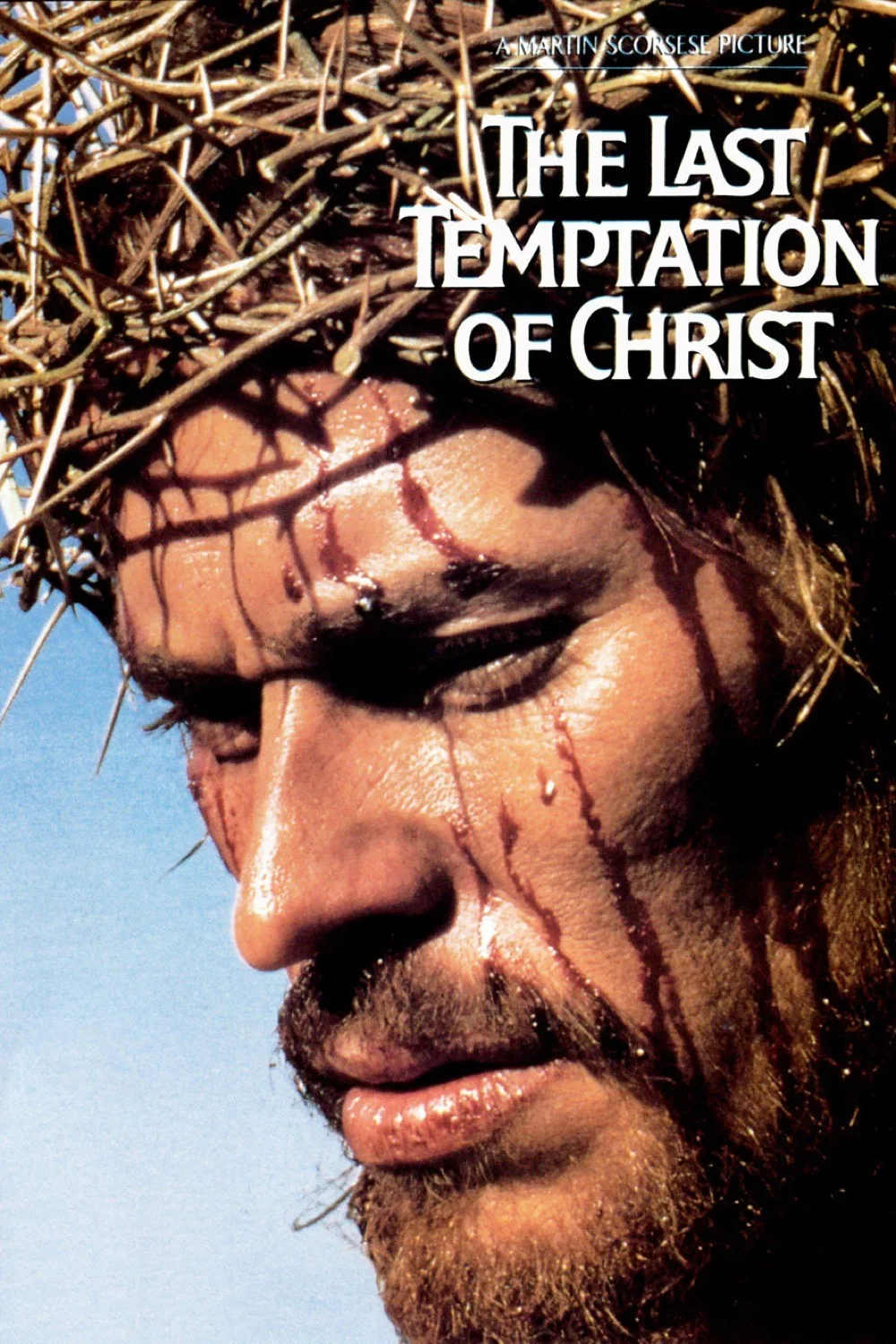

Scorsese and Schrader have not made a film that panders to the audience–as almost all Hollywood religious epics traditionally have. They have paid Christ the compliment of taking him and his message seriously, and they have made a film that does not turn him into a garish, emasculated image from a religious postcard. Here he is flesh and blood, struggling, questioning, asking himself and his father which is the right way, and finally, after great suffering, earning the right to say, on the cross, “It is accomplished.”

The critics of this film, many of whom have not seen it, have raised a sensational hue and cry about the final passages, in which Christ on the cross, in great pain, begins to hallucinate and imagines what his life would have been like if he had been free to live as an ordinary man. In his reverie, he marries Mary Magdelene, has children, grows old. But it is clear in the film that this hallucination is sent to him by Satan, at the time of his greatest weakness, to tempt him. And in the hallucination itself, in the film’s most absorbing scene, an elderly Jesus is reproached by his aging Apostles for having abandoned his mission. Through this imaginary conversation, Jesus finds the strength to shake off his temptation and return to consciousness to accept his suffering, death and resurrection.

During the hallucination, there is a very brief moment when he is seen making love with Magdelene. This scene is shot with such restraint and tact that it does not qualify in any way as a “sex scene,” but instead is simply an illustration of marriage and the creation of children. Those offended by the film object to the very notion that Jesus could have, or even imagine having, sexual intercourse. But of course Christianity teaches that the union of man and wife is one of the fundamental reasons God created human beings, and to imagine that the son of God, as a man, could not encompass such thoughts within his intelligence is itself a kind of insult. Was he less than the rest of us? Was he not fully man?

There is biblical precedent for such temptations. We read of the 40 days and nights during which Satan tempted Christ in the desert with visions of the joys that could be his if he renounced his father. In the film, which is clearly introduced as a fiction and not as an account based on the Bible, Satan tries yet once again at the moment of Christ’s greatest weakness. I do not understand why this is offensive, especially since it is not presented in a sensational way.

I see that this entire review has been preoccupied with replying to the attacks of the film’s critics, with discussing the issues, rather than with reviewing “The Last Temptation of Christ” as a motion picture. Perhaps that is an interesting proof of the film’s worth. Here is a film that engaged me on the subject of Christ’s dual nature, that caused me to think about the mystery of a being who could be both God and man. I cannot think of another film on a religious subject that has challenged me more fully. The film has offended those whose ideas about God and man it does not reflect. But then, so did Jesus.