Years ago I visited one of the great country houses built by the Anglo-Irish in Ireland. It was Lissadell, the very one William Butler Yeats wrote about, its “great windows open to the south.” The Gore-Booth family lived there; one it its daughters, Constance, Countess Markiewicz, was a leader in the Easter Rebellion of 1916, which marked the beginning of the Irish republic and the end for the Anglo-Irish. I went with an Irish friend whose family had grown up nearby. The tour was conducted by a distant relative of the family. As we left, my friend chortled all the way down the drive–that the gentry had so fallen that the son of a workingman could drop some coins in the collection pot near the door.

Deborah Warner’s “The Last September” is set during the next act of the decline of the Anglo-Irish. It takes place in 1920 in County Cork, where Sir Richard Naylor and his wife, Lady Myra, preside over houseguests who uneasily try to enjoy themselves while the tide of Irish republicanism rises all around them. British army troops patrol the roads and hedgerows, and Irish republicans raid police stations and pick off an occasional soldier. It is the time of the Troubles.

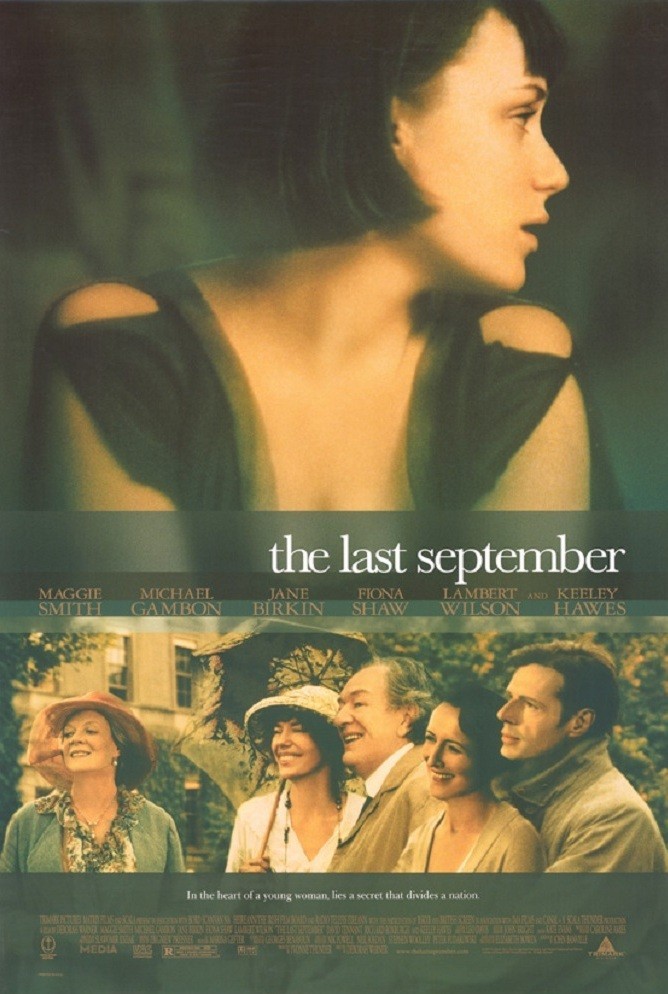

We meet the owners of the great house: Pleasant and befuddled Sir Richard (Michael Gambon) and Lady Myra (Maggie Smith), a sharp and charming snob. She notices that her niece Lois (Keeley Hawes) is sweet on Gerald Colthurst (David Tennant), a British captain, and warns her that, socially, the match won’t do. It would be bad enough if the captain’s parents were “in trade,” but that at least would produce money; it is clear to Lady Myra that the suitor is too poor to afford thoughts of Lois.

Lois keeps her own thoughts to herself and knows that Connolly (Gary Lydon), a wanted Irish killer, is hiding in the ruined mill on their property. She brings him food, but he wants love, too, and she is not so sure about that–although she returns, despite his roughness. Does she love either man? She is maddeningly vague about her feelings and may simply be entertaining herself with their emotions.

Also visiting: Hugo and Francie Montmorency (Lambert Wilson and Jane Birkin), who have had to sell their place and become full-time guests, and Marda Norton (Fiona Shaw), a woman from London who is uncomfortably aware that she is approaching her sell-by date. She and Hugo were once lovers; she wouldn’t marry him, Francie would, and now volumes go unspoken between them.

The weakness of the movie is that these characters are more important as types than as people. The two older women, Marda and Lady Myra, are the most vivid, the most sure of who they are. Hugo is an emasculated freeloader and Capt. Colthurst is a young man in love with infatuation. As for Connolly, the IRA man, he is a plot device.

The movie is based on a novel by Elizabeth Bowen, whose stories of London during the Blitz capture the time and place exactly. She grew up at Bowen’s Court, a country house in County Cork, was a member of an Anglo-Irish family and would have been 21 in 1920–about the same age as Lois. But if Bowen modeled Lois on herself, she did herself no favor; Lois is bright and resourceful and likes attention, but is irresponsible and plays recklessly at a game that could lead to death.

The movie is elegantly mounted, and the house is represented in loving detail, although the opening scenes allow so much of the red-gold sunset to pour into the drawing room that we fear the conservatory is on fire. The tone is one of languid hedonism; life is pleasant for these people, who speak of themselves as Irish, even though to the native Irish, they are merely trespassers for the British empire. I’m not sure the movie should have pumped up the melodrama to get us more interested, but something might have helped.