A group of friends gather for a weekend at a picturesque getaway and become embroiled in each other’s personal business. Old grievances are aired and new grudges materialize. Alcohol is mass-consumed and hanky-panky is pursued. Silly games are played and shouting matches ignite. Lies are revealed and truths are shared. It’s a reliable setup straight out of 1983’s “The Big Chill” (which was preceded and perhaps influenced by 1980’s “The Return of the Secaucus 7”) with its batch of baby-boomer college chums who find themselves reunited for a mutual acquaintance’s funeral.

“The Intervention,” on the other hand, is more like a wake thrown by disillusioned Gen-X’ers as they mourn the crumbling marriage of one of the four couples present. Instead of reverting to behavior from their youthful pasts like their counterparts in “The Big Chill,” these 30-somethings are stuck in a self-deluded limbo when it comes to acting like adults. Forget smoking pot and dancing to Motown oldies. They sneak outside for cigarettes, play a lame version of kickball and can’t seem to summon enough passion for their partners to actually complete the act of sex. There are laughs but mostly of the rueful variety.

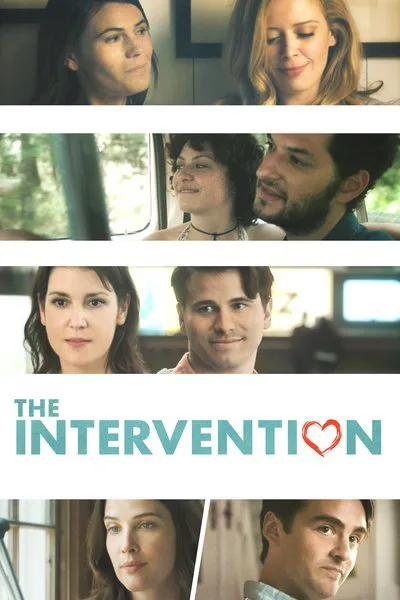

This first feature directed by actress Clea DuVall does get a bit of a cultish lift from the fact that her cast features three key players from 1999’s gay-themed “But I’m a Cheerleader”—Melanie Lynskey, Natasha Lyonne and DuVall herself. And, as before, Lyonne and DuVall are a lesbian twosome. The trio of accomplished ladies do their part to make this less-than-original dramedy at least watchable as does the pretty Savannah, GA, locales.

Still, the central presumptuous notion that one should feel entitled to encourage the dissolution of a troubled marital relationship in this manner somehow feels off. Few people would take kindly to such an intrusion upon their private lives. Perhaps it is for the best that DuVall, who is also the screenwriter, provides plenty of buildup—too much of it involving long shots of the cast lounging around a coffee table, a kitchen table or a picnic table—before the inevitable uncomfortable confrontation arrives.

Thankfully, Lynskey—an underappreciated talent ever since she had the mixed blessing to co-star with a luminous Kate Winslet in 1994’s “Heavenly Creatures,” a breakout debut for both of them—can wring welcoming comedy from emotional anguish. Her Annie, the prime motivator behind the so-called intervention, has her own matrimonial anxiety to deal with as she continually postpones her wedding to nice-guy Matt (Jason Ritter). We also see early signs that she might have a bit of a drinking issue as she guiltily switches her in-flight drink order from O.J. to Scotch. A double no less.

Eventually, they meet up with Lyonne’s Sarah and DuVall’s Jessie and head off to a stately summer home owned by Jessie’s family. Arriving next in a pick-up truck pulling a trailer is Jack (Ben Schwartz), who is currently aimlessly roaming around the country alongside Lola, his much-younger and predatory bi-curious squeeze (Alia Shawkat as a Meg Tilly-like outsider à la “The Big Chill”) whose very presence brings a disapproving scowl to Annie’s face. When asked if Lola was born when the film “Titanic” came out, Ben says, “No, but I’ve explained it to her and she knows how it ends.” Actually, Lola says she is 22 so she was around in 1997, but never mind.

Bringing up the rear is the miserable pair of the hour, Jessie’s sister Ruby (Cobie Smulders, hobbling on crutches, actually broke her the leg the day before shooting started—now that’s commitment!) and husband Peter (Vincent Piazza), a workaholic who adds a half hour to their trip by pulling off to make an important call. These two can bicker over anything it seems, from the exact age of their youngest of three children to an ill-advised discussion of Hitler.

Yet, probably my favorite moment in the film is when Ruby and Peter team up for charades. DuVall is able to cleverly show that, despite their contentious relationship, they possess an almost psychic connection. When Ruby puts her hand on her wrist briefly, Peter instantly guesses the two-word film is “The Untouchables.” When she imitates a vicious animal, he quickly surmises the five-word answer is, “The Unbearable Lightness of Being.”

But, otherwise, DuVall doesn’t give us enough information about her characters—how they all met, what their actual professions are, common reminiscences—for us to relate to or even much care about anyone. The male characters fare the worst, even if we learn of a life-changing tragedy in Jack’s life. Most damaging is the fact that none of the eight find much joy in being with one another. DuVall also lacks the Nancy Meyers gene when it comes to allowing audiences to vicariously thrill to swank décor and fabulous feasts.

“The Intervention” is no embarrassment, and any time a woman is allowed to direct a film benefits the cause. But if DuVall’s purpose was to provide a snapshot of her generation, she should have sharpened her focus and dug a little deeper.