A month after Cristina Ibarra and Alex Rivera’s “The Infiltrators” garnered two prizes at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, one of its subjects, immigrant rights activist Claudio Rojas, was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) during what was supposed to be a routine appointment. His subsequent deportation to Argentina, severing him from his family in the states, appears to have been a clear retaliation for Rojas’ attempts chronicled in this documentary to undermine Florida’s Broward Transitional Center, a for-profit institution that specializes in detaining immigrants without a trial or court-appointed lawyer.

Its prisoners have included a political refugee from Venezuela, a victim of domestic abuse from the Congo and Rojas himself, who leaked secrets about the inner-workings of the corrupt establishment with the aid of the National Immigrant Youth Alliance (NIYA). The majority of the events onscreen are ominously perched in the months leading up to the election of Trump, a president whose favoring of a border wall is as guaranteed as his unwillingness to provide executive orders for those seeking asylum in the United States.

Watching Ibarra and Rivera’s film during this period of pandemic is especially harrowing, since it was just reported this week by NPR that of the very few immigrants detained by ICE who have been tested for COVID-19, half of them have received a positive diagnosis. It is already unconscionable that a nation comprised of immigrants would warehouse those who are undocumented in a system that refuses to recognize their allegedly unalienable rights, and to keep them confined there at the increasingly palpable risk to their survival is a crime. The monolithic U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency, which we’re told is twice the size of the FBI, is the Goliath to the NIYA’s David, and to penetrate the walls of its holding centers requires a good deal of ingenuity.

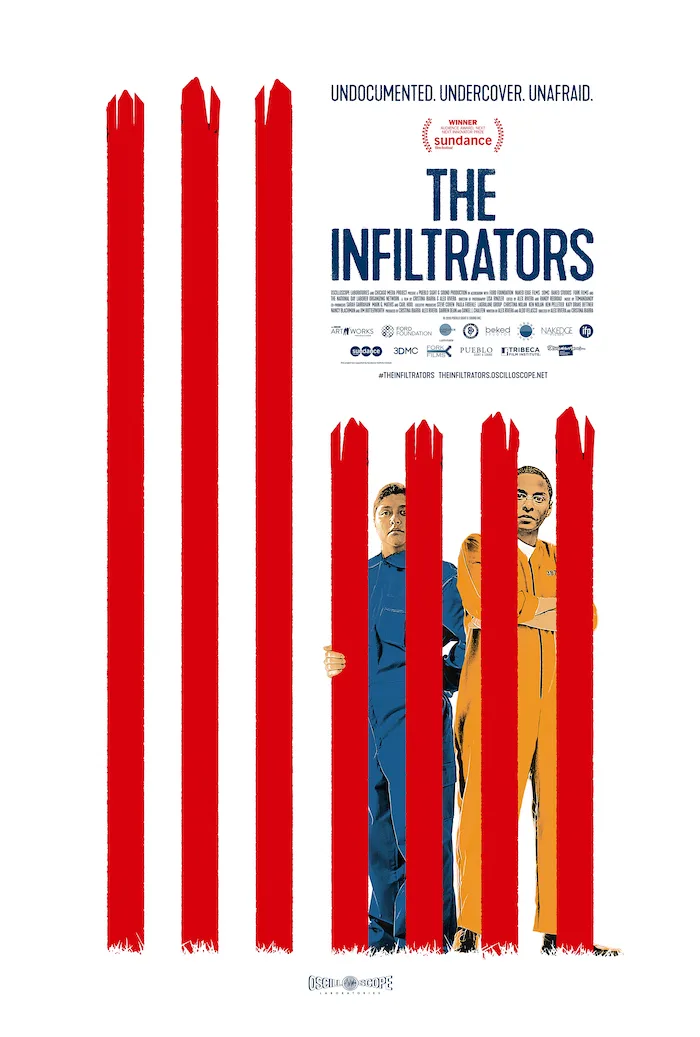

In some ways, “The Infiltrators” is reminiscent of 2018’s under-seen gem “American Animals” in how it blurs the line between narrative and documentary while incorporating genre tropes into the nonfiction medium. Rather than follow the formula of a heist flick, the film occasionally takes the form of a prison break thriller, as young Dreamers from the NIYA led by Marco Saavedra get themselves intentionally detained so that they can work from the inside, connecting with fellow immigrants while pressuring the system into freeing the wrongfully incarcerated one by one. A series of chillingly claustrophobic overhead shots view Broward’s inhabitants wandering about their outdoor cage in orange jumpsuits, so close to the surrounding world and yet stamped down into the earth.

Though “The Infiltrators” isn’t nearly as stylish as “American Animals,” and is somewhat more convoluted, it has the benefit of having subjects who are infinitely more sympathetic. Most compelling of all is Viridiana Martinez, the young NIYA member who practices what she’ll say to Border Patrol as if rehearsing for a school play, while her partner-turned-director Mohammad Abdollahi encourages her to maintain a “natural desperation.” It’s in these moments where the story most effectively coalesces with Ibarra and Rivera’s self-aware style.

I would’ve loved to have seen much more footage of Abdollahi guiding Martinez into embodying the stereotypes they’ve advocated against in order to dupe officials. The tensest sequence occurs during their first stab at using Martinez as “bait,” where a slew of small mistakes threaten to blow their cover. Holding Obama accountable for his assertion that no criminals will be placed behind bars, the NIYA’s chief goal is to be disruptive, blocking traffic and flooding government offices with petitions until their cries are heard (props to Amy Goodman of “Democracy Now” for devoting airtime to their stories). Abdollahi’s reasons for not returning to Iran are in part due to the fact that his sexual orientation as a gay man will prevent him from finding acceptance there, a detail briefly addressed that leaves an indelible mark.

Since so much of the action occurs within Broward’s forbidden walls, the filmmakers resort to staging scenes between the inmates and juxtaposing them with real footage of their allies directing them from the outside. When toggling from an actual subject to their fictional counterpart, the actor’s name will flash on the screen, a touch that’s a bit excessive since the recreations are easy to decipher from the other footage. In fact, the film’s nagging problem is that its conflicting styles never fully gel. The actors’ behavior registers as noticeably stilted and bland when contrasted with the actual subjects, whose flubs and triumphs occurring in real time make for much more suspenseful viewing than set-pieces shot and blocked like a TV movie.

There are long tracking shots that succeed in illustrating the sleight of hand techniques implemented by the prisoners, yet they lack a real sense of urgency, as do the performances (the narration is so soft-spoken, it verges on sleep-inducing). At one point late in the film, rain pours onto the actual subjects as sunlight visibly streams through a window in the staged footage. The incongruous juxtaposition of these approaches constantly took me out of the movie, yet in terms of visualizing the story, the actors do an efficient job of filling the blanks, while detailing how to navigate an inherently corrupt system, such as how to go about obtaining more visitors. The most seamless illusion occurs when Abdollahi converses with one of the inmates—voiced by an actor—on the phone. Less successful is the moment when an actor is made to flap his gums to audio so murky it’s incoherent, though that misstep is thankfully a fleeting one.

What’s most amazing about the stories shared here is how simple acts of rebellion, such as the refusal to board a plane, can delay one’s deportation, at least initially. There’s enormous poignance in how Ibarra and Rivera use imagery of open doors to symbolize the illusion of freedom, which Rojas charges toward in a euphoric slow-motion shot, only to hit an inevitable wall offscreen. An equally powerful shot earlier on frames one of the immigrants in a doorway as he is pressured by ICE into leaving the country so that the well-being of his wife and child will be secured. So many families have been robbed of their loved ones because of systemic xenophobia, and “The Infiltrators” serves as a touching ode to those tireless activists unafraid to fight for their dreams. It is a flawed but important film with a great one straining to break free.