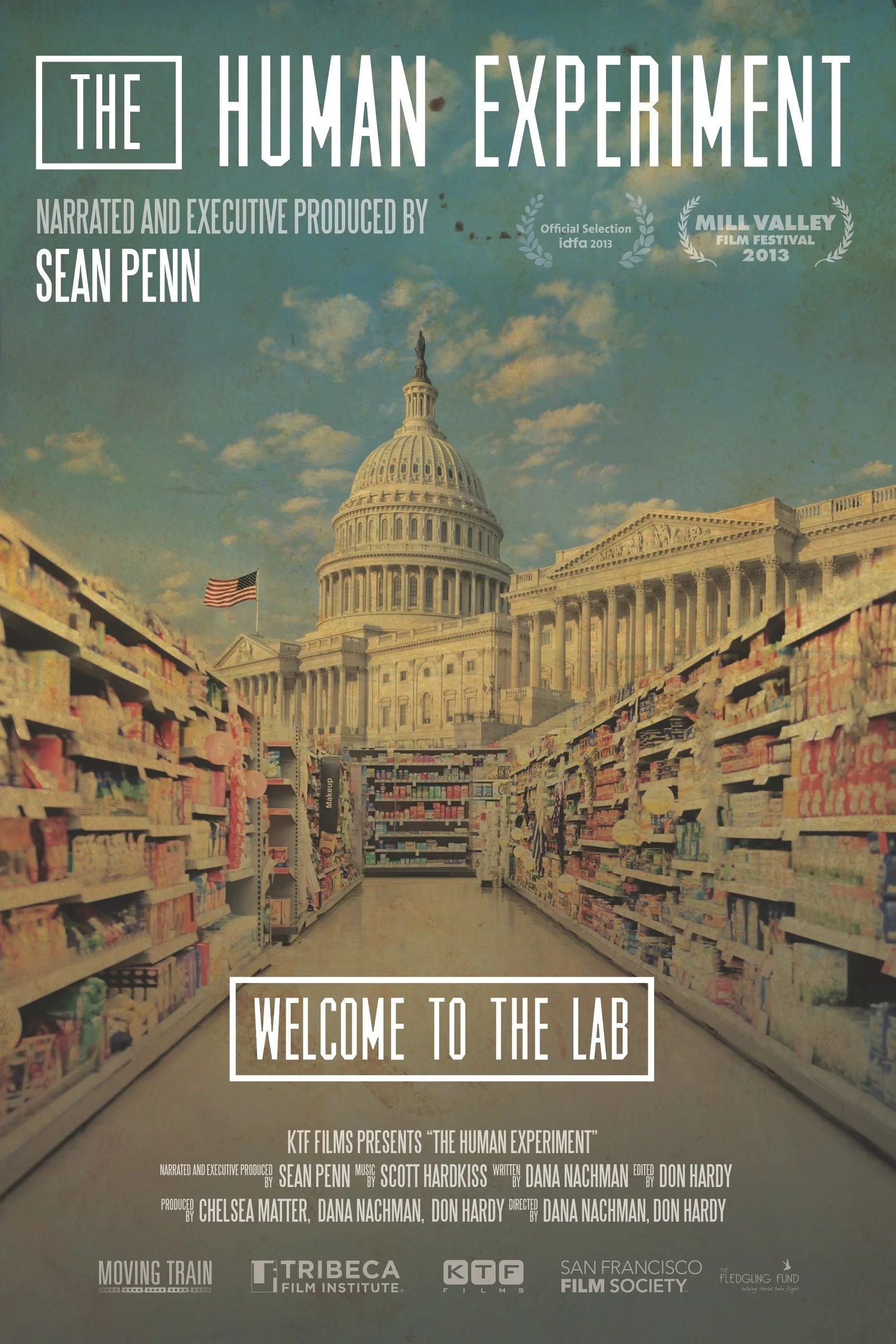

Many of the social issue documentaries that attract the greatest attention—think “An Inconvenient Truth” or “Bowling for Columbine” —combine focused subjects with authorial points of view that are distinctive, forceful and individual. Don Hardy and Dana Nachman’s “The Human Experiment” lacks these qualities. Its subject, the threat of manufactured chemicals in the environment, is a sprawling, amorphous one. And though Sean Penn executive-produced the film and voices its spare narration, the doc has a very generic tone, so much so that it might seem to belong on TV rather than in theaters.

Yet these characteristics do not fatally undermine the film, which gradually marshals its arguments and evidence in such a way that it ends being compelling and illuminating for viewers who are more interested in useful information than artful presentation.

Most people will approach the film having heard that concern over chemicals in the environment has grown in the last couple of decades as their mounting use has been paralleled by dramatic rises in maladies ranging from birth defects to various cancers to autism. There’s not just a handful of such chemicals setting off alarm bells; there are hundreds. The illnesses they’re linked to are also legion, while the connections between them are sometimes more strongly circumstantial than fully established.

“The Human Experiment” starts out by sketching in the range of these phenomena via interviews with people who’ve had medical problems that are thought to be chemically related and doctors who’ve been studying them. The narrative soon enough turns to the economic and political forces behind the overall situation.

These chemicals came into the environment, of course, because they were profitable for the companies that marketed them. Any that preceded the first efforts at government regulation were effectively “grandfathered in” so that their use couldn’t be challenged, and newer ones were introduced without full-scale testing or oversight. Then, when environmentalists began probing their links to various problems, the companies put profits before public safety, throwing up p.r. smokescreens aimed at inhibiting public awareness and government action.

The game plan they followed was the one used so successfully for decades by the tobacco industry (and probed in greater detail in Robert Kenner’s “Merchants of Doubt”): from sewing doubt about the actual science to creating their own bogus data and “experts,” the companies positioned themselves as champions of personal liberty, saying that using their products—no matter how questionable—was a matter of individual choice. Needless to say, they were simultaneously able to throw tons more money into lobbying than their opponents were.

One example of how this worked is explored in the case of flame retardants used on fabrics and other materials. In 1975, California passed a law requiring their use. In recent years, as the chemicals in retardants were shown to be environmentally hazardous and their effectiveness in preventing fire deaths was questioned, a group called Citizens for Fire Safety began running ads advocating their continued use as a way of protecting children—a seemingly laudable goal. Yet the group was not the grassroots activists organization it appeared to be but a front created by the American Chemical Association. Eventually, the ruse was exposed and efforts to change California’s law succeeded.

For much of its length, “The Human Experiment” can feel repetitious, as we see a succession of blandly-shot talking heads discoursing on one chemically-related problem after another. Of course, autism and breast cancer are very different sorts of problems, but the film’s treatment of them effectively just adds them to a long list of ailments that scientists have linked to environmental causes. Yet in its last third, the film moves from presenting the problems to showing how there is movement toward solving some of them—a movement with notable developments on two fronts.

At the international level, Europe has taken the lead in restricting environmental hazards and requiring chemical companies to prove the safety of their products before they are introduced. These policies have been studied by many non-European countries, with the result that their model has taken hold in nations as far-flung and environmentally crucial as India and China. And you can bet some Americans are startled to learn China has certain environmental protections that are better than those in the U.S.

But there’s movement in America too, much of it on the state and local levels. That’s where “The Human Experiment” become most engaging: by showing how a lot of ordinary Americans in diverse locales get concerned about these problems—often by being affected by them personally—then educate themselves and start working with friends and neighbors and sympathetic lawmakers to change the relevant laws.

It’s a heartening example of democracy in action. Spreading awareness of the problems and their potential solutions is a big part of the process, and in that sense, “The Human Experiment” itself will be a useful tool for those involved in these multi-pronged battles.