The story told in “The House of the Spirits” is a lusty, passionate Latin melodrama, filled with ghosts, magic, poison and romance. The material demands to be handled with cheerful abandon.

But by some strange alchemy the film turns the story into a brooding, intellectualized drama. There are still ghosts, but they have all the verve of Hamlet’s father.

The movie has been written and directed by Bille August, a Dane who directed Ingmar Bergman’s autobiographical screenplay “Best Intentions.” It strikes some of the same notes, which worked in a story about chilly Swedish Lutherans, but seem anacronistic in a story set on a South American ranch and filled with lust, violence, revolution and blood vows of revenge.

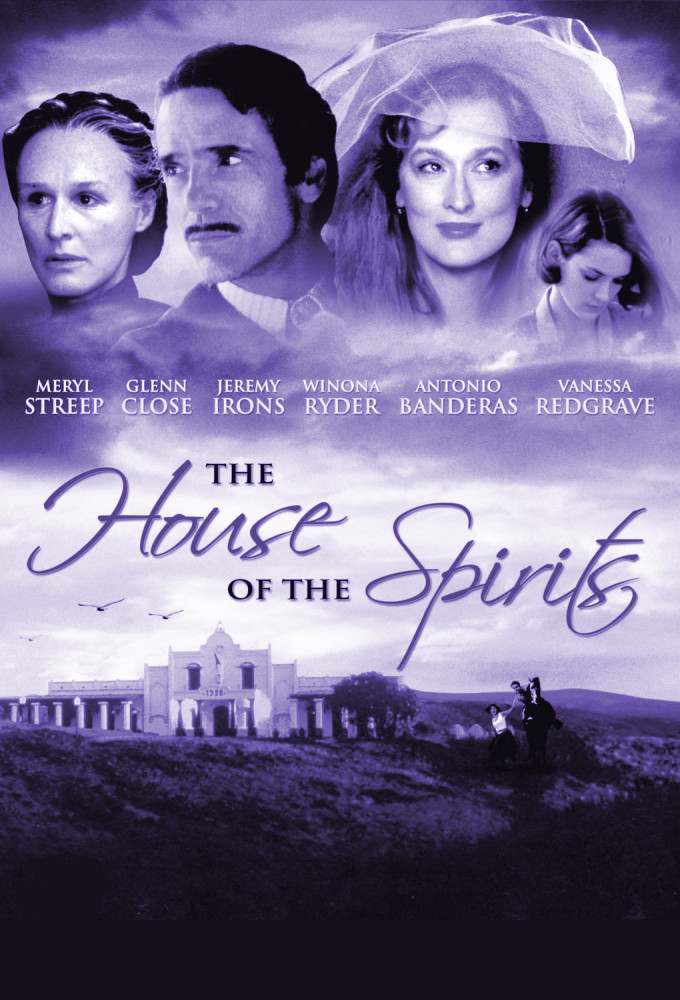

And what odd thinking must have gone into the casting of the movie: Jeremy Irons, Meryl Streep and Glenn Close form a checklist of the “last actors you’d think of while reading the famous novel by Isabel Allende, widow of the slain Chilean leader. To borrow Mark Twain’s complaint about women’s swearing, “They know the words, but not the music.” It is not that Irons, Streep and Close are bad actors here; not at all. Irons in particular does a wellcrafted job of aging from a very young man to a very old one. But whatever he does, he always seems to be a man in the wrong society. As an ancient senator, outraged by being treated with lack of respect, he seems more like a transplanted European earl than an offended South American landowner.

Winona Ryder, who plays the daughter of Irons and Close, also seems an unlikely casting choice (especially if you think of her in “The Age of Innocence“), but she is more convincing, with more abandon and passion, and she makes her character work.

The story spans three generations of a family that lives in a country not unlike Chile or Argentina. As it opens, an ambitious young man named Esteban (Irons) is in love with a rich man’s daughter, and vows to become rich enough to marry her. Laboring in the gold fields, he makes good on his promise – but then, after his fiance is killed by poison meant for her father, Esteban moves to an isolated ranch and devotes 20 years to turning it into a showplace.

Along the way he demonstrates his cruelty and selfishness by raping peasant women and crushing his workers under an iron heel.

One day he returns to the city, and sees his fiance’s younger sister Clara (Meryl Streep), now grown to young womanhood. She has taken a vow of silence years before, but breaks it to tell him, “You have come to propose marriage to me.” He takes his bride back to his ranch, where in the fullness of time they have a daughter (Ryder).

She falls in love with the son of Esteban’s foreman – a hotheaded young man named Pedro (Antonio Banderas) who preaches revolution to the workers.

Now the stage is set for what the publicists like to call a stirring tale of love and tragedy, set against a backdrop of revolution and revenge.

Esteban has been established as a thoroughly rotten scoundrel, so selfish he banishes his own sister (Close) from the ranch for growing too friendly with his wife. He shoots at Banderas to drive him away, he beats his wife, he alienates his daughter, and, still not satiated, he runs for the Senate as a conservative. Meanwhile, the child he fathered out of wedlock, by raping the peasant woman, has grown up into a sullen young man (Joaquin Martinez) who watches his father broodingly from afar, and blackmails him into sending him to the national military academy, so that when there’s a military coup we are hardly astonished when he reappears as a torturer.

In Allende’s story, Clara is a clairvoyant with telekinetic abilities – gifts her family accept rather casually. “No, Clara!” her mother sternly instructs, when the little girl uses mind-power to move a candlestick. On her wedding night, she causes a table to levitate, and Esteban wearily pushes it back into place. Magic realism, which informs so many South American stories, is treated here as a slightly embarrassing social gaffe, like passing wind.

Clara’s gifts are not made integral to the story; the filmmakers see them more as ornamentation.

The movie works on a certain level simply because it tells an interesting story. The characters are clearly drawn, the story provides ironic justice, and the locations establish a certain reality. The cluttered city homes of the rich families, where every surface is lined with expensive bric-abrac, speak eloquently for their materialistic values and traditions.

But contrast this movie with another film based on a famous Latin novel of romance and revenge, “Like Water For Chocolate.” That film breathes from its roots and informs us with its passion. “The House of the Spirits” seems like a road production – like a French “Guys and Dolls,” an Italian “Three Sisters,” a British “A Streetcar Named Desire.” All of the characters have the right names, all of the necessary events occur, and indeed the very best local actors have been engaged. But the soul has been mislaid.