“The Horseman on the Roof” is a rousing romantic epic about beautiful people having thrilling adventures in breathtaking landscapes. Hollywood is too sophisticated (or too jaded) to make movies like this anymore; it comes from France, billed as the most expensive movie in French history.

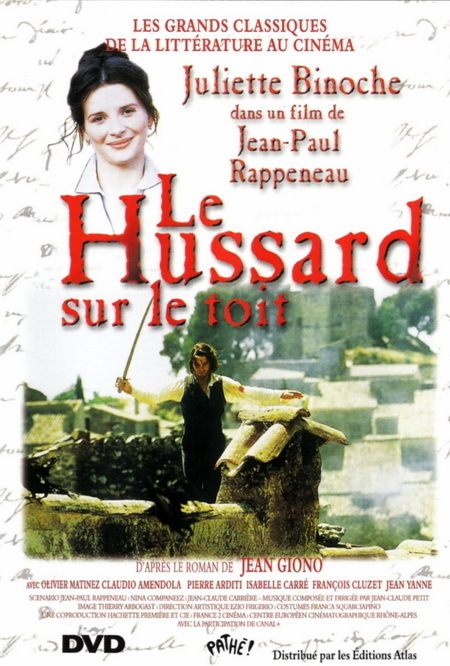

It’s a grand entertainment, intelligently written, well-researched, set in the midst of a 19th century cholera epidemic. A newcomer named Olivier Martinez stars as an Italian patriot named Angelo Pardi who has escaped to France from the Austrian invaders who have overrun the north of his own country. There he encounters the beautiful Pauline de Theus (Juliette Binoche), wife of a French nobleman, who bravely seeks her older husband in the plague- and terror-ridden land.

Of course these two people are destined to fall in love. But “The Horseman on the Roof” wisely delays the inevitable; it’s as coy as “The African Queen” in the way its two lead characters share adventures and danger while denying, to each other and to themselves, that a strong attraction is growing between them.

Pauline was 16, the daughter of a country doctor, when she married her husband, who was 40 years older. Now she wants to return to the quarantined areas of France, where the cholera epidemic lays waste whole villages, to find him. Angelo comes along, to aid and protect her, and their quest is told in scenes of action, adventure and fascinating historical detail.

The most memorable visuals in the movie involve the epidemic–its victims, the panic it inspires, and especially the carrion birds that stalk fearlessly among the dead and dying. (At one point Pauline is attacked by a bird, and observes, “They don’t fear men since they have started to eat them.”) There are scenes here that reminded me of similar moments in “Restoration” (1995), another lavishly produced period film about a world in the grip of disease. At one point Angelo pauses in a village to drink from a well, and is attacked and nearly killed by the villagers, convinced that he is a well-poisoner. In another scene, a mayor’s elegant dinner party is reduced to anarchy by the merest suggestion that someone at the table might be contagious.

Eventually, still seeking her husband, Pauline voluntarily goes into quarantine–into a vast makeshift hospital set aside for the dying and their loved ones–and Angelo follows her. The scenes here are fearful and touching, and we learn a little of the crude medical resources, mostly based on ignorance, that were being used against cholera. Not much was known about how germs spread disease, but in one scene, after the characters have possibly been contaminated, they rub alcohol on their skin and set it briefly alight, to kill the bacteria.

But the movie is mostly about adventure and romance, not hospital wards, and there are thrilling stunt and special-effects sequences, directed by Jean-Paul Rappeneau with an eye for the small detail as well as the vast canvas (Angelo escapes from a mob by fleeing over rooftops, and his progress is intercut by the movements of an inquisitive little cat, which follows him fearlessly and curiously).

Martinez, as the hero, is a new leading man in the style of the young Jean-Paul Belmondo, who starred in films like “Cartouche.” Binoche usually plays sophisticated young women of the world (she was the woman gripped by sexual passion in Philip Kaufman’s “Unbearable Lightness of Being” and Louis Malle’s “Damage,” and the composer’s widow in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s “Blue”). This time she is much simpler–a woman loyal to her husband, for whom duty is a higher calling than passion.

Her reserve, and the instinctive chivalry of Angelo, create a sexual tension between them that is more interesting because it is not acted upon. Their restraint sets the stage for an eventual development all the more romantic because it is based on love and faith, not carnal satisfaction.

“The Horseman on the Roof” was produced by the French in an attempt to recapture their own domestic market from the inroads of Hollywood’s big-budget romantic action extravaganzas. Whether it can find the same audiences in North America is more doubtful; the movie may be too broad for the art-house crowd and too subtitled for everyone else. But it satisfies an old hunger among moviegoers: It is pure cinema, made of action, beauty, landscape and passion, all played with gusto, and affection.