It always begins with the Wrong Gas Station. In real life, as I pointed out in my review of a previous Wrong Gas Station movie, most gas stations are clean, well-lighted places, where you can buy not only gasoline but groceries, clothes, electronic devices, Jeff Foxworthy CDs and a full line of Harley merchandise. In horror movies, however, the only gas station in the world is located on a desolate road in a godforsaken backwater. It is staffed by a degenerate who shuffles out in his coveralls and runs through a disgusting repertory of scratchings, spittings, chewings, twitchings and leerings, while thoughtfully shifting mucus up and down his throat.

The clean-cut heroes of the movie, be they a family on vacation, newlyweds, college students or backpackers, all have one thing in common. They believe everything this man tells them, especially when he suggests they turn left on the unpaved road for a shortcut. Does it ever occur to them that in this desolate wasteland with only one main road, it must be the road to stay on if they ever again want to use their cell phones?

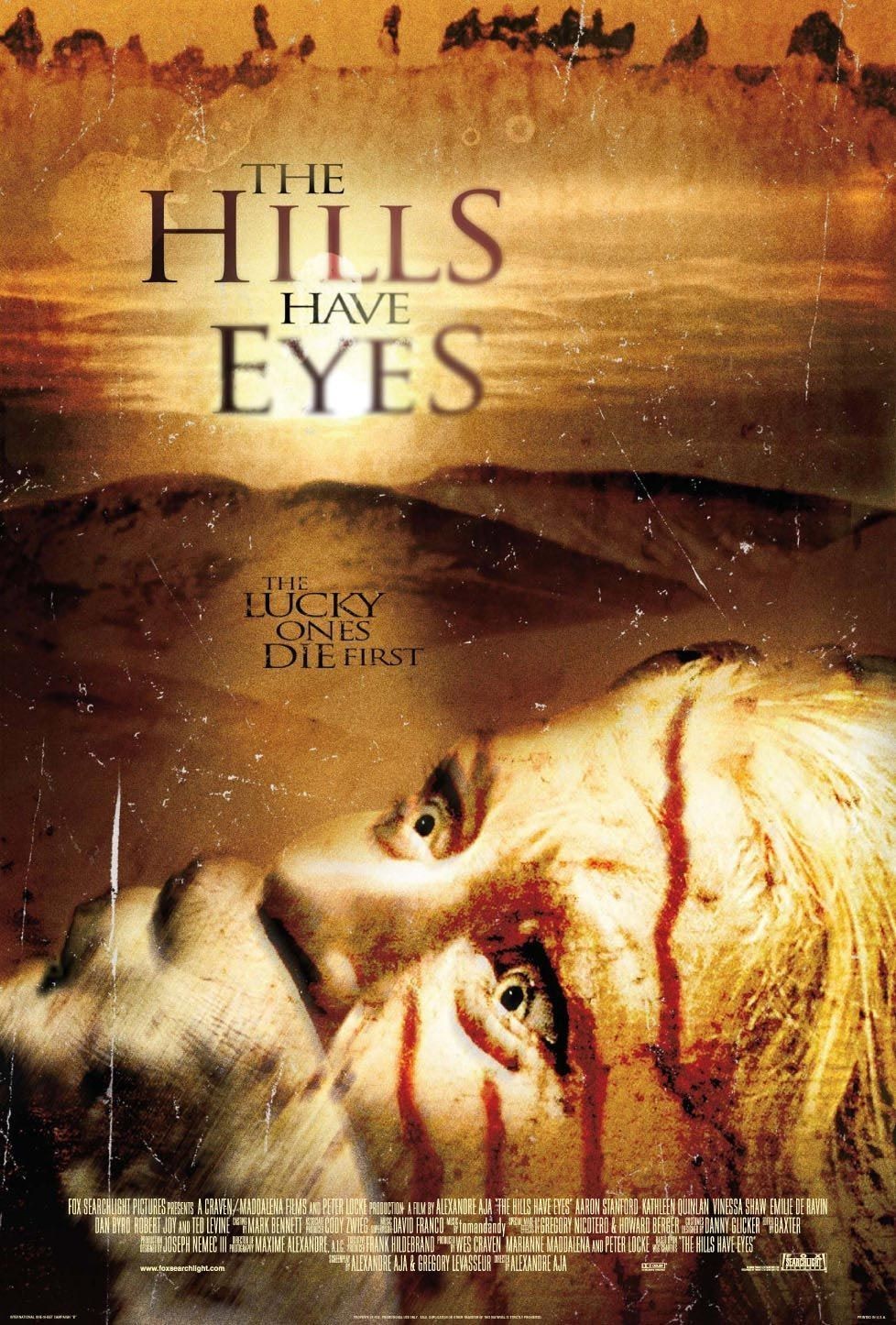

No. It does not. They take the fatal detour, and find themselves the prey of demented mutant incestuous cannibalistic gnashing slobberers, who carry pickaxes the way other people carry umbrellas. They occupy junkyards, towns made entirely of wax, nuclear waste zones and Motel Hell (“It takes all kinds of critters to make Farmer Vincent’s fritters”). That is the destiny that befalls a vacationing family in “The Hills Have Eyes,” which is a very loose remake of Wes Craven’s 1977 movie of the same name.

The Carter family is on vacation. Dad (Ted Levine) is a retired detective who plans to become a security guard. Mom is sane, lovable Kathleen Quinlan. A daughter and son in law (Vinessa Shaw and Aaron Stanford) have a newborn babe. There are also two other Carter children (Dan Byrd and Emilie de Ravin), and two dogs, named Beauty and Beast. They have hitched up an Airstream and are on a jolly family vacation through the test zones where 331 atmospheric nuclear tests took place in the 1950s and 1960s.

After the Carters turn down the wrong road, they’re fair game for the people who are the eyes of the hills. These are descendants of miners who refused to leave their homes when the government ordered them away from the testing grounds. They hid in mines, drank radioactive water, reproduced with their damaged DNA, and brought forth mutants, who live by eating trapped tourists. There is an old bomb crater filled with the abandoned cars and trucks of their countless victims. It is curiously touching, in the middle of this polluted wasteland, to see a car that was towing a boat that still has its outboard motor attached. No one has explained what the boat was seeking at that altitude.

The plot is easily guessed. Ominous events occur. The family makes the fatal mistake of splitting up; dad walks back to the Wrong Gas Station, while the dogs bark like crazy and run away, and young Bobby chases them into the hills. Meanwhile, the mutants entertain themselves by passing in front of the camera so quickly you can’t really see them, while we hear a loud sound, halfway between a swatch and a swootch, on the soundtrack. Just as a knife in a slasher movie can make a sharpening sound just because it exists, so do mutants make swatches and swootches when they run in front of cameras.

I received some apppalled feedback when I praised Rob Zombie’s “The Devil's Rejects” (2005), but I admired two things about it: (1) It desired to entertain and not merely to sicken, and (2) its depraved killers were individuals with personalities, histories and motives. “The Hills Have Eyes” finds an intriguing setting in “typical” fake towns built by the government, populated by mannequins and intended to be destroyed by nuclear blasts. But its mutants are simply engines of destruction. There is a misshapen creature who coordinates attacks with a walkie-talkie; I would have liked to know more about him, but no luck.

Nobody in this movie has ever seen a Dead Teenager Movie, and so they don’t know (1) you never go off alone, (2) you especially never go off alone at night, and (3) you never follow your dog when it races off barking insanely, because you have more sense than the dog. It is also possibly not a good idea to walk back to the Wrong Gas Station to get help from the degenerate who sent you on the detour in the first place.

It is not faulty logic that derails “The Hills have Eyes,” however, but faulty drama. The movie is a one-trick pony. We have the eaters and the eatees, and they will follow their destinies until some kind of desperate denouement, possibly followed by a final shot showing that It’s Not Really Over, and there will be a “The Hills Have Eyes II.” Of course, there was already “The Hills Have Eyes II” (1985), but then again there was “The Hills Have Eyes” (1977) and that didn’t stop them. Maybe this will. Isn’t it pretty to think so.