A country house and a corpse. Yes. We are comfortable already. It is a big house, with a sweeping staircase, and doorways through which we glimpse life continuing just as if the owner were not dead upstairs. That must be the cook setting the table. But wait. The camera, having climbed the stairs and regarded the dead body, slides on down the corridor and looks through another door, where a young woman sits on the floor, distraught. We have come up these stairs just a few seconds too late to be eyewitnesses to murder.

Claude Chabrol has been climbing these stairs all of his life, and discovering the secrets of the French bourgeois. Many of his murderers have the easy manners of good old families. Before we go back downstairs and join the story of “The Flower of Evil,” which is his 50th film, we should pause for a moment to honor this milestone. Chabrol was one of the founders of the French New Wave, so early he did not know it was the New Wave and he was founding it. As a character says in “Citizen Kane,” he was there before the beginning and now here he is, after the end. “He began directing in 1958,” Stanley Kauffmann writes in the New Republic, “and has never committed an ill-made film, has rarely made a dull one, and has occasionally created a gem.”

I shared an enormous sea bass once with Chabrol in a New York Chinese restaurant, and on another night we did some drinking and talked about his latest film. That was in 1972, at the New York Film Festival. Five years earlier Andrew Sarris had already been able to write about Chabrol in the past tense: “He quickly became one of the forgotten figures of the nouvelle vague.” Now it is 2003 and Chabrol still has his hand in. So does Sarris. “With respect to Mr. Chabrol’s ‘The Flower of Evil,’ he writes tactfully in the New York Observer, “I would prefer to think of it as a masterly work of the artist’s late period rather than as the tired product of his old age.”

And so we beat on, boats against the current. I feel such an affection for Chabrol and his work that I probably can’t see “The Flower of Evil” as it would be experienced by a first-time viewer. Would that newcomer note the elegance, the confidence, the sheer joy in the way he treasures the banalities of bourgeois life on his way to the bloodshed? And would they understand the truly savage quality that lurks just under the surface-the contempt he feels for these characters who move in such style between their jobs and homes, their political campaigns and love affairs? Here is a movie in which the one romance which nearly everyone approves of is between a brother and a sister.

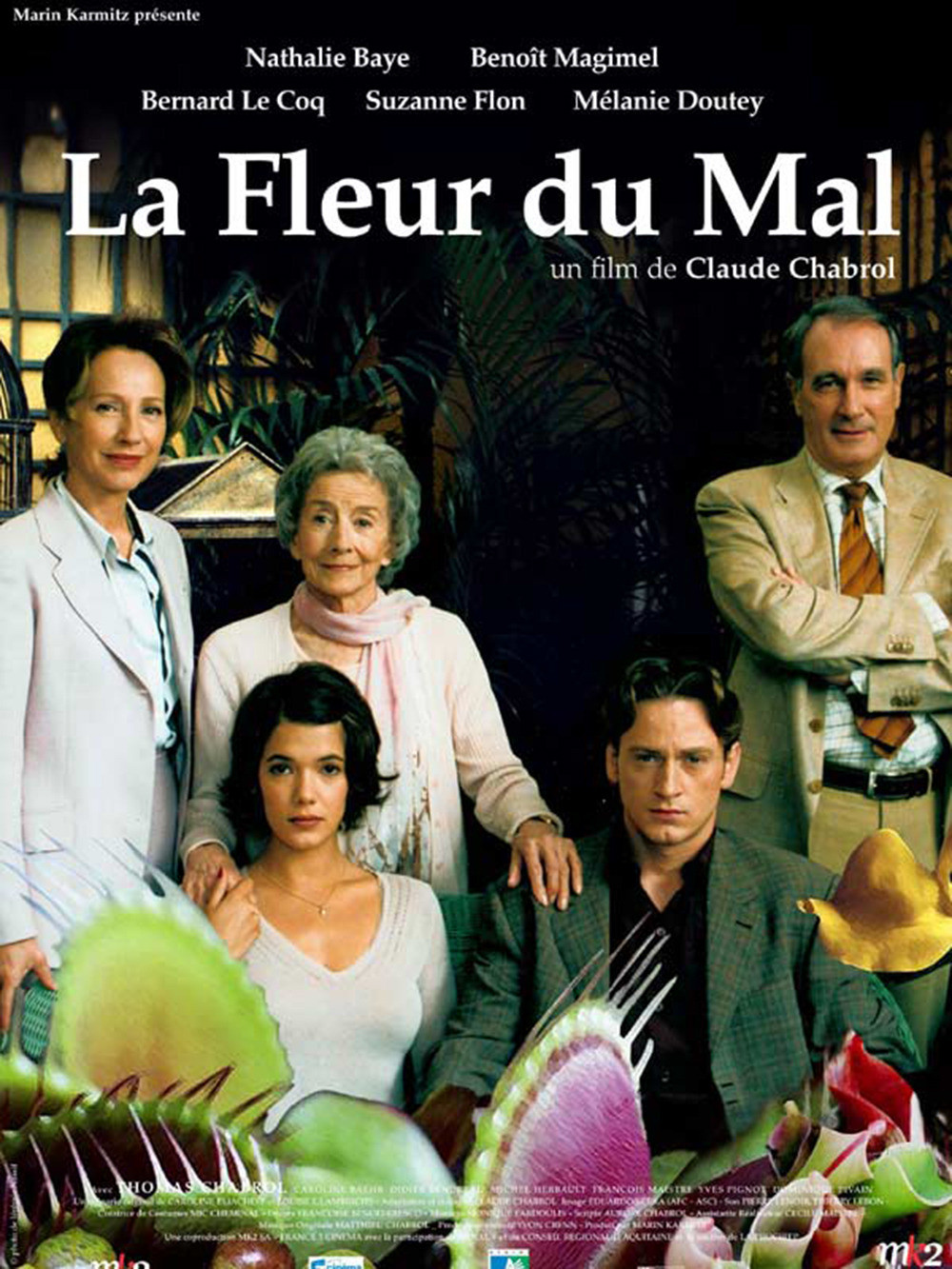

Their incest requires footnotes: Francois (Benoit Magimel) is the son of Gerard Vasseur (Bernard Lecoq); his mother was killed in an accident, and so his father married Anne Charpin-Vasseur (Nathalie Baye), who brought a daughter into the marriage. This is Michele (Melanie Doutey). So Francois and Michele aren’t technically siblings — but they are cousins, because this family has been intermarrying for generations. Francois flew off to Chicago to study law for four years (“The Americans are not as stupid as they like to pretend”), but he couldn’t outgrow his infatuation with Michele, and soon after his return they borrow the holiday cottage of old Aunt Line (Suzanne Flon) and consummate what they have so long imagined.

The family is remarkably unruffled. There are other plots afoot. Gerard has made a fortune with his semi-legal pharmaceutical factory. His wife is using his money to run for local office, and Gerard has had enough of the way that she drags her political adviser Matthieu (Thomas Chabrol) to family gatherings and dinners. Matthieu tries to make his excuses and slip away, but Gerard insists he stay, the better to make him feel uncomfortable.

Someone in the town has sent around an anonymous letter libeling three generations of the family for collaboration with the Nazis, profiteering, corruption, adultery, incest and not being nice. Most of these charges are true, as old Aunt Line has reason to know, and after Chabrol’s elegant establishing scenes and hints of buried shame there is, all of a sudden, a shocking revelation, a dead body, a woman sitting on the floor, and this time the police are coming up the stairs.

Chabrol’s buried theme, as frequently, involves the rotten French monied class. He attacks the rich not as a leftist but simply because he is fastidious and cannot stand them. He has also found time for murderers of the middle and lower classes, but his heart quickens when he finds death in corrupt suburban villas.

A boxed set of six classic Chabrol DVDs has just been issued, and if you want to see him among the working classes, rent “Le Boucher,” one of his two or three best films, which is about an elegant schoolmistress who falls in love with a charming butcher, only to be faced with the possibility that she is about to be filleted.