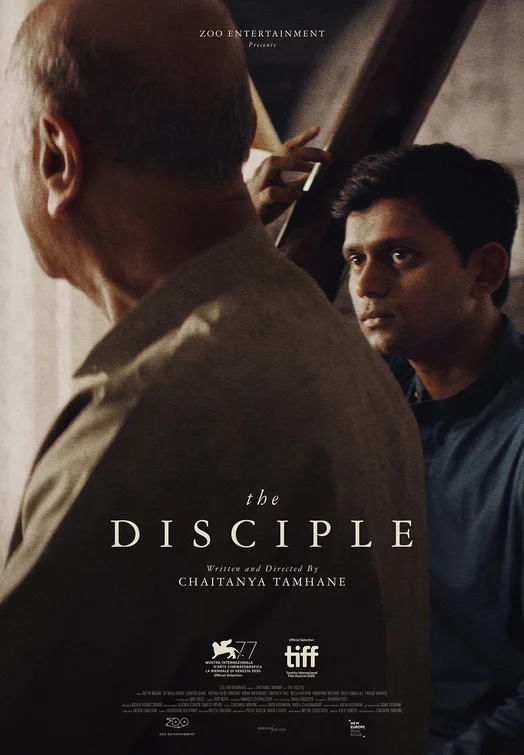

Sometimes we love art so much that we forget it does not have to love us back. Writer/director Chaitanya Tamhane’s “The Disciple” reminds us of this by telling the story of Sharad (Aditya Modak), who has been looking past such a bittersweet truth his whole life. In his pursuit of becoming a master vocalist in Indian classical music, his happiness has become muted. And it does not matter how much he studies his idols, or practices at night, pushing himself through one mistake after another. There is something more to music than just technique, and time. “The Disciple,” in its own powerful way, is about an avid practicer who would give anything for this dream, but does not have “it.”

Sharad has wanted this since he was a boy. His father trained him extensively, made him knowledgeable beyond his years about the music and its theory, and imparted Sharad with a desperation to be great. Currently, he lives with his grandma, and by day he earns minimal pay converting old classical recordings into new audio formats, archiving music that people hardly listen to anymore, and that he loves. By night, he bikes around Mumbai listening to bootleg teaching tapes from a master named Maai, whose singing advice includes finding purity, perspective, and inner truth. These scenes are shot in dreamlike slow motion, to match the droning of the tanpura, an instrument meant to be support a voice. And these sequences often run for over a minute, forcing the viewer to slow down themselves. Such flourishes add a substantial deal to the story’s approach of getting you inside Sharad’s head.

Tamhane has a brilliant approach to involving the viewer into the film’s many musical sequences, whether one has listened to Indian classical music before or not. At first it’s about setting the stage: before any music is even heard, Tamhane’s framing is already vibrating with people moving about in their chairs, fanning themselves, milling about in small but cumulative ways. (It’s not uncommon during the whole movie for people in the background to walk in and out of frame at meticulous times.) But when it comes to the performance, Tamhane commands your attention not by telling us which musician to look at, but to notice everyone’s expressions. It’s a film with music that’s all about faces, namely that of performers, a recognization of how musicians can have their own silent monologues while their hands focus on their instruments. Long before Tamhane’s camera gently pushes into Sharad’s gaze, its expressions going from supportive, humbled, jealous, and insecure, back to focus on his tanpura, and back again, we know that we should be paying attention to him even more than the man warbling his throat at the center of the frame with impeccable breath control and microtonal confidence, his Guruji.

“The Disciple” is a great example of when filmmaking and acting styles complement each other, and it’s that bond that feels to be a significant part of what makes Tamhane’s film so special, so resonant. On the outside, Modak goes through distinct physical transformation in the film, complementing Tamhane’s decades-spanning narrative than then goes back and forth at a blink. But the inside work is even more compelling: Modak creates an emotional desperation that is as organic as Tamhane’s static camera, the actor repressing a tremendous deal of emotions behind polite smiles and forceful gulps of self-loathing with each failure. Being a good musician requires a certain presence in the moment; the same goes for acting. Modak’s incredible performance, especially when he’s on stage or practicing alone, transcends those two ideas, and achieves the type of purity that Sharad yearns for.

Looking into Sharad’s progressively beat-down eyes, I thought of another weary movie musician who struggled with the classics: Llewyn Davis. That character, from the Coen brothers masterpiece “Inside Llewyn Davis,” also loved the music that no one wanted to hear any more, and became isolated in wanting to preach its greatness. But “The Disciple” is even bleaker than “Inside Llewyn Davis,” as at least Oscar Isaac’s character harnessed the essential feeling behind music—the difference between simply repeating what has been heard before, the “it.” Sharad cannot find that feeling despite being told to pursue it by those he looks up to, and Tamhane obfuscates the notion even more by wondering if feeling really matters at all. Especially when it comes to the classics, which Tamhane posits as a cause more lost than Llewyn’s friend’s cat.

“The Disciple” depicts a full lifetime of being someone like Sharad, by jumping to his different memories as a kid, a 24-year-old entering competitions, and later a man in his thirties. It is a non-fussy approach: when things get slightly better for Sharad’s career, there is no grandiose improvement montage that shows his skills, but rather an indication of how his insistence might have finally pushed him to the next level. (A photoshoot in the future adds a mustache, a bunch of belly weight, and a photographer reminding him that he should smile.) There is another perceptive scene in the film in which Sharad encounters a critic who challenges the legacy of all the music he reveres; it’s all the more wrenching to be used as a flashback, as if it were a course-altering conversation he’s tried for decades to deny. But it’s the personal details that, at least on first viewing of “The Disciple,” feel too sketched out by Tamhane’s non-chronological editing. With the character study pushing past two hours with its solemn tone, the leaps register as abrupt and slightly cold to the emotional growth it wonders about earlier in the film during his times of arrested development, or when he fails to have a healthy romantic relationship.

Here is a film that you should know before going in is particularly sad, and yet that is what makes it so meaningful. The movie shares Sharad’s passion for Indian classical music, dedicating some long and sprawling sequences to displaying it and talking about it, but “The Disciple” dares to look at passion as a state of mind with sizable pain. Sharad’s journey of wanting to be like his idols is filled with so many flubs—called out by his master, or sometimes by himself—and each time they’re a little punch to the gut, but oh so recognizable. And yet he keeps at it, with a degree of endurance that would usually be triumphant. In the unsentimental reality of Tamhane’s film, it is incredibly devastating, and honest.

Now playing on Netflix.