Tommy Wiseau’s cult hit “The Room” leaves the audience with massive questions. Not just about pictures of spoons, strange dialogue, or the star’s penchant for smashing things, but curiosities of a more baffling nature: From what mind and soul did this entirely serious production come from? How could an artistic statement like this exist?

The enigma of Wiseau is only partly addressed by James Franco’s “The Disaster Artist”. The movie treats his lack of self-awareness and transparent loneliness as a sweet novelty instead of treating him as a complicated human being, someone worthy of empathy. Though sporadically inspired, especially when trying to call back to the magic of filmmaking in “The Room,” Franco’s film suggests that it’s easier to laugh at a clown than to attempt to understand why they’re in the make-up.

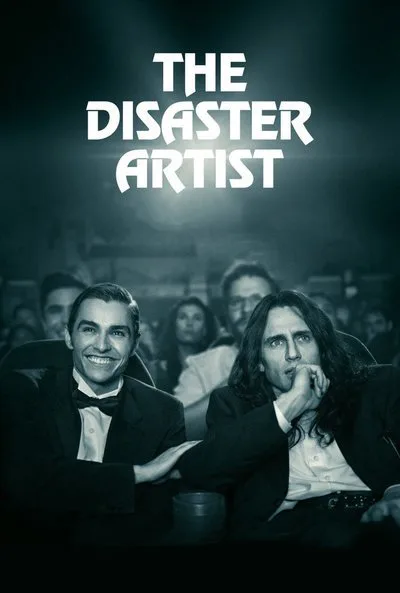

The simplistic approach starts with the relationship between Wiseau and his friend/actor/line-producer Greg Sestero, a hollow center for this story. Wiseau (James Franco) is a shadowy man of ambiguous older age and accent origin, with a bombastic presence in acting classes (in one bit, he just repeats “Stella!” a la Marlon Brando but with none of the context). He’s discovered, or rather noticed, by a real-life reflection of what Wiseau is not: an all-American, conventionally handsome rising actor named Greg (Dave Franco). They are united by their common desire to become famous actors and they eventually move to Los Angeles, where Greg is more successful in getting auditions than Tommy.

Played from its opening whimsical guitar score as a sweet story about friends, the dynamic of a real-life, Apatow-brand bromance is prominent, and makes for a few funny bonding moments, like when Tommy has Greg loudly rehearse a scene in a restaurant as a ridiculous gesture of fearlessness. But it thins out as the story goes along, especially as Greg appears so obedient, and unquestioning to the eccentric Tommy, only to break that type of friendship focus when he meets Amber (Alison Brie). Their friendship has a crucial lack of stakes, despite its unique nature, and the legendary film project that eventually comes between them.

And then, “the masterpiece.” In an effort to be noticed in Hollywood, Tommy decides to make his own movie (which he compares to the likes of Tennessee Williams), and disregards his complete inexperience as a film director. He buys cameras instead of renting them, creates a set of an alley way instead of just shooting in an alley, films on both 35mm and HD at the same time, and that’s before they even start actual production. Greg goes along with it, smiling through the process, and Tommy becomes a clueless clown to a crew that are, in the movie’s comedic context, all his straight men.

Working from a script that adapts “The Disaster Artist” for its goofy moments and less for its heart or perspective, the story grabs select tidbits from the real-life sets, creating can’t-believe-it’s-true comedy, with recognizable faces (Seth Rogen, Paul Scheer, Jacki Weaver, Josh Hutcherson, Ari Graynor, Nathan Fielder) placed in the vision of Wiseau through Franco’s recreation. And the second half of the movie is funny in large part because “The Room” is funny. So, it’s a special boost when actors come in playing ridiculous characters, and offers the most inspired bits. Casting Nathan Fielder to play the stuffy psychologist Peter, or watching Jacki Weaver saying the famous line, “I got the results of the test back. I definitely have breast cancer.” There are guaranteed laughs just in seeing who plays who, like with Josh Hutcherson having that floppy-parted hair of Denny.

It’s easy to see why Franco would be attracted to the project. They are both artists without borders, directors who lead with ambition before they lead with reason. It’s all the more disappointing to see that the movie has little perspective of its own aside from Franco inserting Wiseau’s filmmaking into the Franco kaleidoscope. There is a lacking critical quality to the story as it goes along, touching upon the film’s many idiosyncrasies but leaving them alone. When Tommy’s misogyny is on display during a scene of filming—laughing about a woman getting beat up and sent to the hospital, despite being told over multiple takes not to—”The Disaster Artist” doesn’t question what’s underneath it. And yet when the movie does want to analyze “The Room,” it’s one of many cringing, on-the-nose moments where a funny person is delegated with spoon-feeding the audience (in this case it’s the usually hilarious June Diane Raphael).

Franco the Actor prevails more than Franco the Director. In front of the camera, he has the voice, that strange amalgam accent that sounds sometimes like just airy ditzy-ness. At times, his stoic face can be heartbreaking, lost in this valley of being both self-conscious and completely not aware of himself at the same time. But Franco the storyteller fails this character by taking the easy way out. Segments are played specifically to laugh about his accent, or that he doesn’t remember his lines, without going deeper into where that stubbornness comes from.

For all of its potential, in both the original source and even from the movie itself, the heart of “The Disaster Artist” is smaller than it should be. The friendship arc continues to have a touch-and-go handling and the movie itself egregiously abridges the film’s natural, long ascent into cult status with its ending, the strangest of its kind since Danny Boyle’s “Steve Jobs.”

While much has been made about whether or not those unfamiliar with “The Room” could enjoy this work, the opposite may be true—”The Disaster Artist” made me wonder briefly if I love “The Room” too much. But as the movie started to slip away, aside from its own novelty of seeing famous people recreate one of my favorite movies, it started to become more apparent. I see Wiseau as an artist, and his film as one made from a singular vision however many bad choices it may include. It all makes for a baffling true Hollywood story, along the lines of what Tim Burton did for “Ed Wood,” but the “Plan Nine” director emerged from that film redefined as a passionate creator. By the end of “The Disaster Artist,” Wiseau is still a joke.