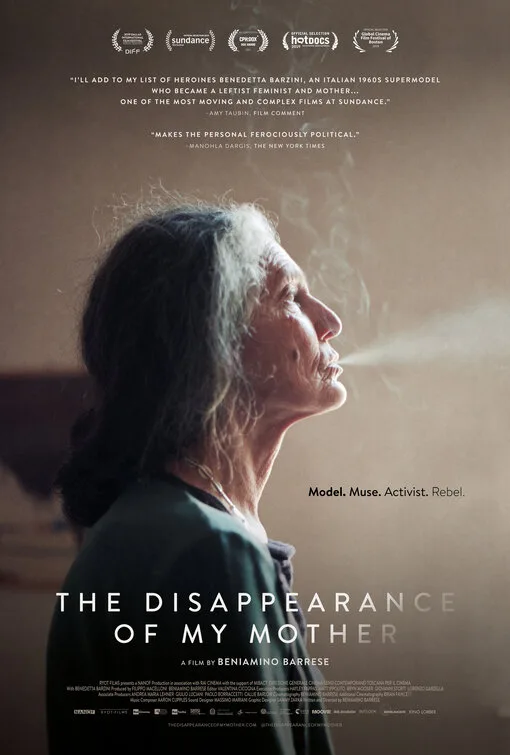

Benedetta Barzini does not like photographs. To her, they are static, flat, dead. “I don’t like frozen things,” she says. Even just snapping a photo to capture a happy moment takes on an almost sinister context. She complains, “Nothing is left to memory … your own memory.” If you are so busy trying to capture the moment, you miss the moment. You miss your life. She is ferocious on this point: “I have nothing to do with images.”

These comments, repeated in endless variations throughout “The Disappearance of My Mother,” a documentary by Beniamino Barrese (Barzini’s son), are fascinating in and of themselves on a philosophical level (one thinks of Susan Sontag’s book about photography), but also intriguing because Barzini was a supermodel, discovered by Diana Vreeland, and the first Italian to appear on the cover of American Vogue. Pale and slim, with gigantic almost mournful eyes, cheek punctuated by a beauty mark, Barzini was photographed by the likes of Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. Drawn into Andy Warhol’s circle through her friendship with Gerard Melanga, she appeared in one of Warhol’s screen tests, her long zebra-striped gown highlighting her face as she grinned mischievously up at artist Marcel Duchamp. Looking at her high-fashion magazine spreads, one is aware of her self-awareness: the shapes she makes with her body are often asymmetrical and angular, creating startling images. You can see why fashion designers and photographers loved her. Born in 1943, Barzini is now 76 years old, living in a cluttered house in Milan, teaching courses on the fashion industry, bringing a cool-eyed feminist critique to the entire enterprise. “Men invent women, and this leads to Jessica Rabbit,” she sneers.

All of these tensions roil through “The Disappearance of My Mother,” which is a son’s attempt to capture his mother, who seems desirous of vanishing completely. She talks about moving to an isolated island, where she would never have to see anyone or hear from anyone ever again. She wants to “disappear.” What this disappearance might look like is up for interpretation, and Barrese seems both curious about her eventual disappearance—he wonders if they can “stage it” together—and also anxious about capturing as much of her as possible. He zooms in on her different parts, her mole, her eyes, her long grey hair. He hovers over her, filming her while she’s asleep. And this just after she complains about the “bloody camera” being pointed at her all the time! Even more complicated, she barely cooperates with his project. She constantly tells him to stop filming her, looking right at the camera, swearing at him. He’s the paparazzi. At one point, Lauren Hutton comes to visit, and Barrese tries to film their reunion before Hutton turns on him, too: “You need to stop. This is our friendship.” In other words: you’re intruding, our friendship doesn’t need to be captured in order to exist, go away. In our Instagram-ready current world, such thoughts go so against the grain there’s almost no place for them anymore. But Hutton is right, and her honesty about it is refreshing.

Barrese follows his mother everywhere. She bikes to teach her classes, and there’s lots of thought-provoking footage of her lectures and small conferences with students. These are some of the best sequences in the film and—interestingly enough—you get to know Barzini better in these sequences than in the more personal sequences with her son (maybe because Barzini is not as aware of being filmed when she’s in the classroom, and therefore she’s not crackling with irritation). She holds up advertisements for the students, ripped out of magazines, pointing out what the images convey about how women are viewed, how women are commodified and then sold. She speaks of symbols, metaphors, contexts. She asks her students probing questions about beauty and age, and she really listens for each answer. Despite her ambivalence about modeling, she is seen participating in a couple of runway shows, stalking down the catwalk with barely concealed disdain.

Barzini’s background is an interesting one, but Barrese doesn’t really get into the details of it. This is not a biography of Barzini. His interest in her is wholly personal. She is his subject, his fascination, his muse. “Disappearance” is impossible for this woman: she is still recognized wherever she goes. She allows her son to film her, and sometimes even cooperates, although overall she tries to get away from the camera, the camera that has been pointed at her—in some form or another—for 50 years.

Barzini says at one point: “The real me isn’t photographable.”

Benedetta Barzini may want to disappear, but her son will not let her.