“The Deliverance” would have worked just fine if it had functioned solely as a domestic drama infused with the thorny, real-world issues of addiction, poverty and racism.

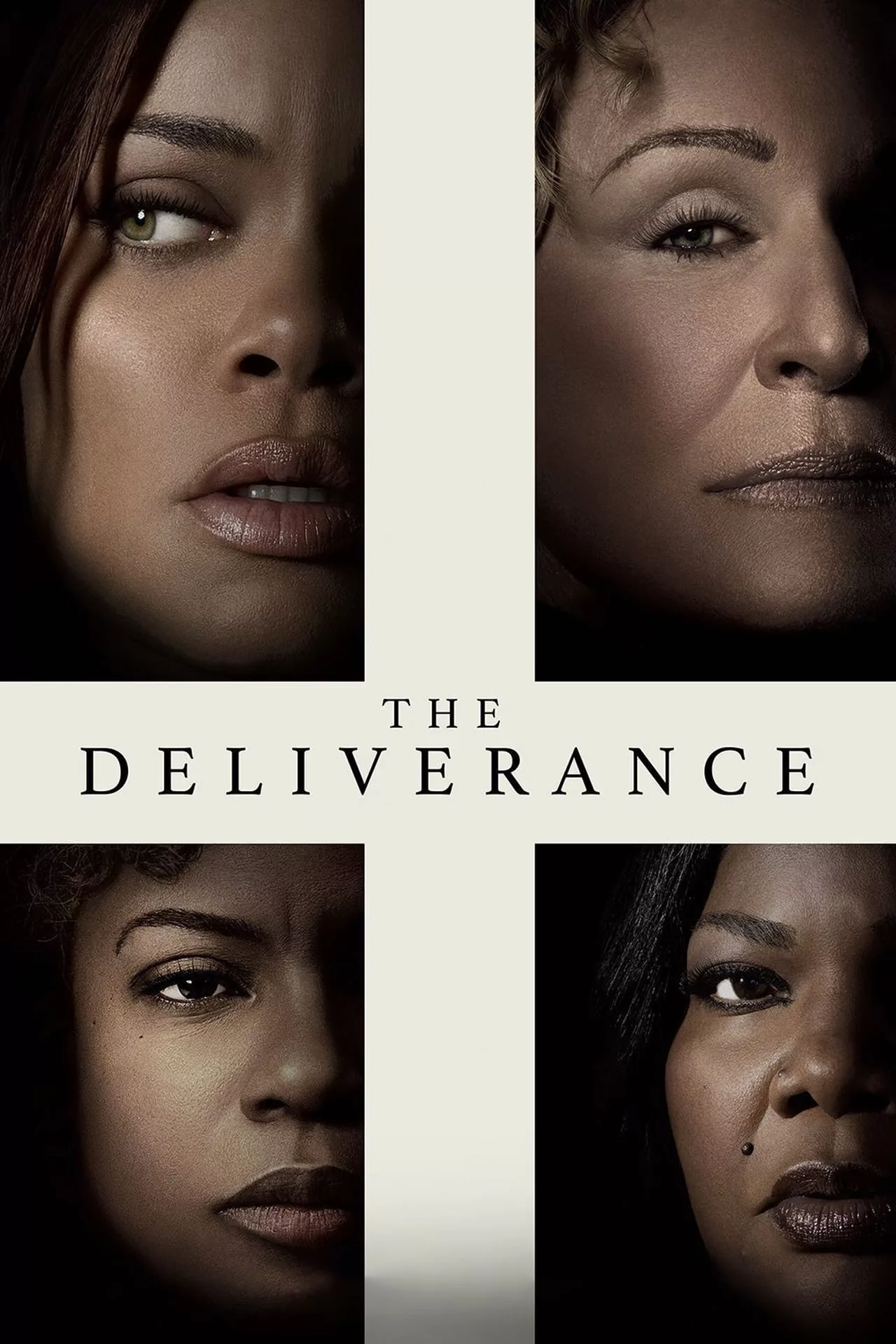

This is territory director Lee Daniels knows well, having given us a searing exploration of these subjects with his Academy Award-winning 2009 film “Precious.” Daniels made his name as a filmmaker with an affinity for difficult characters and raw relationships, as we’ve also seen in “The Paperboy” and “The United States vs. Billie Holliday.” And he’s amassed an impressive cast here, including Andra Day, Glenn Close, Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor and “Precious” Oscar winner Mo’Nique.

But he’s taken all that promise and tacked a standard horror story about demonic possession onto it. He’s trying to slam two different movies together, with uneven and increasing unconvincing results. Once “The Deliverance” turns into a full-tilt genre movie, it offers the kinds of scares we’ve seen countless times before: kids skittering up walls and lingering in the air, graphically vile invective spewing from the mouths of babes, and the crack-crack-crack of evil contorting bodies in unnatural positions.

Trouble is, “The Deliverance” is far more effective when Day’s single-mom character confronts her metaphorical demons, rather than her literal ones.

The film is inspired by the case of Latoya Ammons, who moved with her family into a Gary, Indiana, rental home in 2011. Soon, she began noticing strange occurrences and disturbing behavior from her children. Eventually, a priest conducted an exorcism, and the house was demolished.

Here, screenwriters David Coggeshall and Elijah Bynum have taken that core notion and moved it to the unstable home of Day’s struggling mother, Ebony, in working-class Pittsburgh. Day has an immediacy to her screen presence that can be startling, a volatility that makes her fearsome even before anything starts going bump in the basement. Raising three kids–teenagers Nate (Caleb McLaughlin) and Shante (Demi Singleton) and their younger brother, Andre (Anthony B. Jenkins)–while also tending to her own mother (Close), who’s suffering from cancer, would be enough responsibility for one person to handle alone. But Ebony is also an alcoholic fighting a constant battle to stay sober. Dealing with her mother, Alberta, offers its own set of challenges–and Close, chain smoking in a collection of flashy wigs and cold-shoulder tops, gives a brash performance that makes her Mamaw from “Hillbilly Elegy” look demure and mindful.

This time, Mo’Nique is the one investigating reports of abuse and neglect in the home as an agent of Child Protective Services, and that’s before the kids start acting erratically in school. A scene in which Ebony delivers a swift backhand to her youngest child for talking back at the dinner table reveals that such concern is warranted. Mo’Nique brings a world-weariness to the role but also a feeling of genuine concern. Similarly, Ellis-Taylor offers warmth and strength as an apostle–don’t call her an exorcist–who might just be the family’s salvation. But while Ellis-Taylor’s graceful presence is always extremely welcome, the supernatural element of the story that her character ushers in marks the point at which the film starts to decline.

It’s not that “The Deliverance” becomes too unsettling; quite the contrary, once it’s obviously about a demon feasting on Ebony’s family, it feels too safe. We’ve seen these images and heard these words before. What’s frustrating is that Daniels is a filmmaker known for leaning into the lurid, for milking the melodrama. He takes risks, for better and for worse, and that’s exciting. For a while, Ebony is an unreliable conduit into this scenario, so it’s intriguingly unclear as to what’s happening in a drunken haze and what’s a legitimate threat.

But once the film shifts into a different gear, Daniels can’t quite match the turbulent intensity he established earlier. There’s nothing in the iffy visual effects that’s as frightening as the real-world threats these kids face just getting through the day. And given the mish-mash of tones at play, it’s sadly fitting that the whole thing ends on an awkward note of rushed uplift.

On Netflix now.