“The Cursed” is a horror film set in the 18th century, about a pathologist investigating a series of bloody animal attacks on a French estate. Written, directed, and photographed by Sean Ellis (“Anthropoid“), it’s visually and atmospherically a knockout, using mist and foliage as well as darkness to set up and intensify the many stalkings, huntings, and horrific attacks.

The style is reminiscent of gorgeous but brutal historical dramas like “Barry Lyndon” and “The Last of the Mohicans,” to the point where it seems not quite right to sum up “The Cursed” as a “werewolf movie.” Ellis’ script draws on familiar elements of werewolf mythology as established in the movie that started the genre, the 1940 Universal Horror classic “The Wolfman,” including certain bits of lore (a person bitten by a werewolf can become a werewolf, but only if they survive the attack) and a strain of exoticism centered on Roma culture (referred to here as gypsies).

The latter ties together class conflict, fear of the “other,” and colonialism. There’s a framing device set in World War I that eventually does pay off at the end (though it doesn’t deepen the movie; it’s just clever), but for the most part, “The Cursed” sticks to one estate in rural France and the surrounding area, where a wealthy family rules over land seized from Roma tribespeople. Their village is destroyed in one of the film’s most impressive sequences, an unbroken, static long take of the mayhem that makes you feel as if you’re watching atrocities from high on a hilltop and are powerless to stop them.

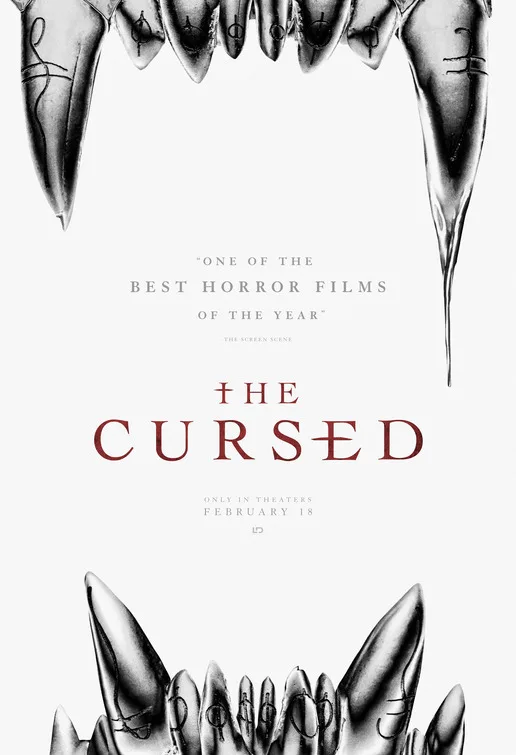

One of the women of the tribe is forced to watch her husband being mutilated and burned to death and raised up on a tall wooden cross to serve as a scarecrow, then she herself is buried alive in an open grave, but not after one of the hired goons working for the landowner finds a human skull-piece: jaws only, its teeth removed and replaced with silver replicas. Then the nightmares begin among the local children, who visualize themselves walking to the site of the murders in the middle of the night and getting involved in weird and ghastly predicaments that are an expression of what we’d might call suppressed cultural guilt. No set of silver teeth in a film like this is going to sit in the ground without being used to bite somebody, and sure enough, soon there’s a creature roaming around, killing some victims and wounding others.

It wouldn’t be sporting to describe the plot in too much detail here, as the most distinctive thing about “The Cursed” is the way it plays around with what we think of as standard werewolf mythology. It’s not just the Marxist-adjacent worldview of the film that fascinates (in one sequence, a servant girl survives being bitten, then wraps her wounds and goes to work because she’s terrified of getting fired for not showing up) but also the theme of suppressed guilt over colonialist, exploitive, even genocidal tendencies among Europe’s ruling classes.

A fascinating strain in literary criticism holds that gothic fictions such as “Wuthering Heights,” “Dracula,” “The Turn of the Screw” and “Rebecca” are at least partly a way to express collective guilt over the bloody sins of colonialism and slavery: the return of the oppressed as well as the repressed. Many of the stories are about a foreign or exiled character, often described as “dark” or “swarthy,” coming to (or returning to) a European country, usually England but not always, to bring drama and havoc to comfortable rich people. “The Cursed” fits within that tradition. It’s surely no accident that the guilty dreams followed by overwhelming violence are initially concentrated among the young: there is even a line about the sins of the parents cursing or “infecting” subsequent generations.

On top of all that, Ellis has fun playing around with the visual aspects of werewolf lore. This is the first werewolf movie I’ve seen where the form of the lycanthrope doesn’t immediately say “wolf.” The depiction of the creature reminds us that we are seeing characters from an era when scientific knowledge was comparatively primitive, and people would use terms familiar from the known world to describe an unknown threat. Pathologist John McBride (Boyd Holbrook) is a soulful, sad Van Helsing-type who’s there to help battle a phenomenon that he saw play out in his own hometown, claiming the lives of his wife and daughter. He initially describes the attacks as the work of a wolf because, we later realize, everyone around him will have trouble accepting the truth.

There’s a bit of crossover with the zombie film (plus two-plus years of Covid-19 denialism) with locals initially refusing to understand and accept that there’s a thing out there that can kill you, and even if you don’t die from it, you can spread it to others, and then they’ll kill, too. Some of the gory and gooey special effects also evoke various remakes of “The Thing,” a monster story that is also a pandemic parable.

It’s all so rich—and so richly executed by Ellis, a total filmmaker—that one wishes it added up to more than a series of smart variations on a certain type of film. The movie clocks in at less than two hours, but as grateful as one may be for relative brevity in the age of blockbuster bloat, there are times when you may wish that the filmmaker had expanded upon one of the many intriguing ideas contained in his script, and followed his own best impulses as an allegory-maker by not copping out at the end by prizing narrative neatness over nightmarish resonance. Considering all its varied ambitions, this is a movie that should lodge in your brain and haunt your dreams for the rest of your life, not send you away thinking how handsomely produced and neatly constructed it was.

All that having been said, the supporting cast, which includes Kelly Reilly, Alistair Petrie, Roxane Duran, and Nigel Betts, is superb, and scene for scene, this is Ellis’ best-directed film, drawing on everything from “The Shining” and “The Innocents” to “Jaws,” the “Jurassic Park” franchise, and even John Sayles’ labor drama “Matewan.” Robin Foster’s grinding, sawing, burbling synth score is outstanding as well, channeling that John Carpenter feeling that there’s something horrible lurking out there in the dark, and it’s going to take its sweet time killing you.

Now playing in theaters.