“That’s the point of a commune. You support each other.” Said by one character at a moment of crisis in Thomas Vinterberg’s “The Commune,” it expresses the ideal of living in community. If a group of people decide to forswear the typical nuclear-family structure, if they decide to pool their resources and go through life as a group, then—ideally—there should be more support present for each individual in said group. If someone falls, multiple people will be there to help pick him back up. But that’s not how it works out, human nature being what it is. People are selfish, people screw up, people keep secrets, etc. It’s a rich dramatic topic, in and of itself. However, “The Commune,” featuring a great ensemble cast (many Vinterberg regulars), doesn’t really focus all that much on what happens when you put a bunch of charismatic individuals into one house. The ensemble is just background noise for the main story, a married couple in a midlife crisis. Pretty bourgeois, considering the “free love” ’70s atmosphere. Maybe that’s the point.

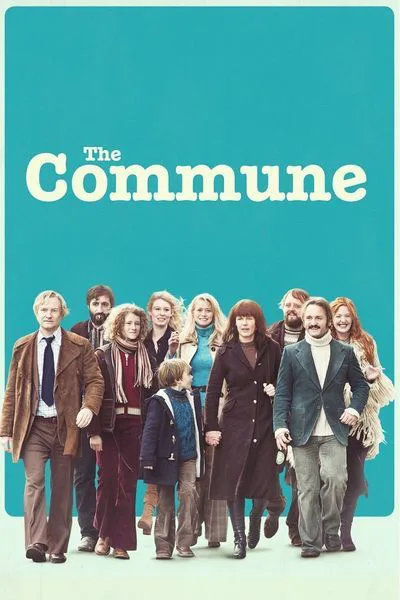

When Erik (Ulrich Thomsen), a professor of architecture, inherits his gigantic childhood home, he assumes he’ll have to put it on the market right away. He and his wife Anna (Trine Dyrholm) have only one daughter, 14-year-old Freja (Martha Sofie Wallstrøm Hansen), and the house is far too big for just three people. Anna, a television news anchor, suggests that they invite some friends to live with them. Share the costs, of course, but also to liven up their humdrum lives a bit. Anna is open about her own boredom in her relationship with Erik: “I need to hear someone else speak. Otherwise I’ll go mad.” The plan gathers steam. One friend signs up, then another. Eventually, the group gels together. They hold formal interviews for new members. They go skinny-dipping together to celebrate their new life, and walk across the street en masse, holding up traffic like rock stars.

There are two children who live in the suburban commune, the aforementioned Freja, and one couple brings their son, a small solemn child with a heart condition. Vinterberg grew up in such a community. It seems like it would be great to be a child in such an environment, surrounded by adults who are not your relatives, people coming and going, leaving you to your own devices. Vinterberg focuses a lot on Freja, her wary watchful face. She’s only 14. She lives in a house with 10 adults, most of whom are drunk the majority of the time. Hansen is a wonderful actress, a beautifully strong presence.

In “The Commune,” life is first one, long, drunken party. The group cooks together, cleans together, eats together. They touch base nightly, keeping a running chart on how everyone is doing. (This situation would be an exhausting nightmare for introverts.) Being truthful and open is required. Anything hidden will fester and cause problems. When Erik starts an affair with a young student named Emma (Helene Reingaard Neumann), he opens up to Anna about it. She is stunned and hurt, but instead of asking him to move out, suggests that he have Emma move in with the group. What could go wrong?

Dyrholm, a superb actress, manages to show—in her behavior, in her glitchy little pauses for thought and reflection—why Anna would make such a suggestion. Anna is so determined to create the kind of life for herself that she wants, a free life, a life where people can live and let live, and so how does one achieve that when one’s heart is breaking, when one’s marriage is falling apart? If she threw Erik out, wouldn’t that be just a petty reversion to conformism? Isn’t the goal to stop being attached to things, including people?

Vinterberg’s harrowing 1999 film “The Celebration” showed his gift for ensemble drama. Having to put up a “front” for the group makes things exponentially worse. This is what happens in “The Commune,” and it’s brilliantly acted (in particular by Dyrholm). But once the marital crackup takes center stage, the movie loses most of its charge.

There are some interesting observations throughout about the human need for dominance, control, order, even in an unconventional environment. No matter how free we are, how liberated, we still feel the need to set up chore charts. Even so-called hippies gravitate towards bureaucracy. Freedom requires organization. The group votes on every decision. Someone says at one point, “Okay, let’s vote on whether to vote.” Ironically, there’s a pull towards conformity. Individualism cannot go up against the group. This is how cults are formed. The commune here does not become a cult, but when Erik suddenly pulls rank, shouting at everyone, “This is MY house,” it’s a perfect representation of the challenge. You’re supposed to give up on the idea of ownership, on the idea of individualism itself.

These are all fascinating concepts, but “The Commune” isn’t all that interested in exploring them.