Thomas Vinterberg’s “The Celebration” mixes farce and tragedy so completely that it challenges us to respond at all. There are moments when a small, choked laugh begins in the audience and is then instantly stifled, as we realize a scene is not intended to be funny. Or is it? Imagine Eugene O'Neill and Woody Allen collaborating on a screenplay about a family reunion. Now let Luis Bunuel direct it.

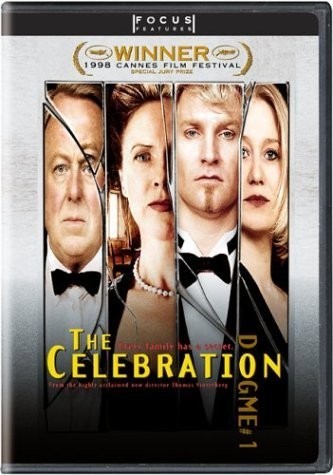

The story involves a 60th birthday party at which all of a family’s corrupt and painful secrets are revealed at last. To the family’s country inn in Denmark come the surviving children of Helge (Henning Moritzen) and his wife, Elsa (Birthe Neuman). We meet the eldest son, Christian (Ulrich Thomsen); his younger brother Michael (Thomas Bo Larsen), and their sister Helene (Paprika Steen). Christian’s twin sister has recently committed suicide. Also gathering around the table for the patriarch’s birthday are assorted spouses, relations and friends.

The film opens with a family in turmoil. The drunk and furious Michael careens his car down a country road while blaming his wife for everything. He comes across Christian, walking, and stops to give him a lift (throwing out his wife and children, who must walk the rest of the way). In their room, Michael starts berating his wife again (she has not packed some of his clothing) before they have rough sex; we assume this vaudeville is the centerpiece of their marriage.

At the birthday banquet, Christian raps his spoon against a glass and rises to calmly accuse his father of having raped his children. The gathering tries to ignore these remarks; Helene says they are not true. In the kitchen, the drunken chef gleefully observes that he has been waiting for this day for a long time, and dispatches his waitresses to steal everyone’s car keys from their rooms, so they won’t be able to escape. Christian rises again and accuses his father of essentially murdering the sister who killed herself.

The evening spins down into a long night of revelation and accusation. The father at first tries to ignore his son’s performance. The mother demands an apology, only to have Christian remind her that she witnessed her husband raping him. Helene’s boyfriend, an African-American anthropologist, arrives late and is the target of Michael’s drunken racist comments. The family joins in a racist Danish song. A servant accuses a family member of having impregnated her; she had an abortion, but still loves him. And on and on, including fights and scuffles and an interlude when Christian is tied to a tree in the woods.

Vinterberg handles his material so cannily that we are must always look for clues to the intended tone. Yes, the family history is ugly and tragic. But the chef, hiding the keys and intercepting calls for taxis, is out of French farce. The fact that the family even stays in the same room is a comic artifice (in farce, you can never just walk away). That nearly everyone is drunk doesn’t explain everything, but that many of them are chronic alcoholics may explain more: This is a chapter in a long-running family saga.

Vinterberg shot the film on video, then blew it up to 35-mm. film. He joined with Lars von Trier (“Breaking the Waves“) and two other Danish directors in signing a document named “Dogma 95,” which was unveiled at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival and pledged them all to shoot on location, using only natural sounds and props discovered on the site, using no special effects or music and using only hand-held cameras. “The Celebration” and von Trier’s “Idiots” are the first two–and may be the last two–films shot in this style. It would be tiresome if enforced in the long run, but the style does work for this film. A similar style is at the heart of John Cassavetes’ work.

It’s a tribute to “The Celebration” that the style and the story don’t stumble over each other. The script is well planned, the actors are skilled at deploying their emotions, and the long day’s journey into night is fraught with wounds that the farcical elements only help to keep open. Comes the dawn, and we can only shake our heads in disbelief when we see the family straggling back into the same room for breakfast.