When the Chicago Film Festival held its evening with Busby Berkeley a few years ago, the effect of three straight hours of production numbers was, well, stupefying. Seen maybe three to a movie, Berkeley’s geometric arrangements of smiling girls were sort of fun. But when you got his entire career in one spliced-together dose, you couldn’t help realizing how little imagination he really had.

Berkeley liked to anchor his camera and give us sterile symmetrical variations on a theme. He got his effects with sheer excess: A hundred dames on a hundred grand pianos was outta sight, all right, but even in the 1930s there were alternatives. In movies like “Swing Time” and “Top Hat,” Astaire and Rogers were creating musicals that feel fresh today. They were supremely talented, of course, but that wasn’t their whole secret.

What they did with a series of directors (and with Astaire usually having a creative hand in the choreography) was to make musicals that were really movies, that weren’t stage bound, and that weren’t riveted to an anchored-down camera. In their movies, we somehow inhabited the same space with them, instead of being omnipotent observers positioned up in the rafters. We moved as they moved, and space unfolded logically.

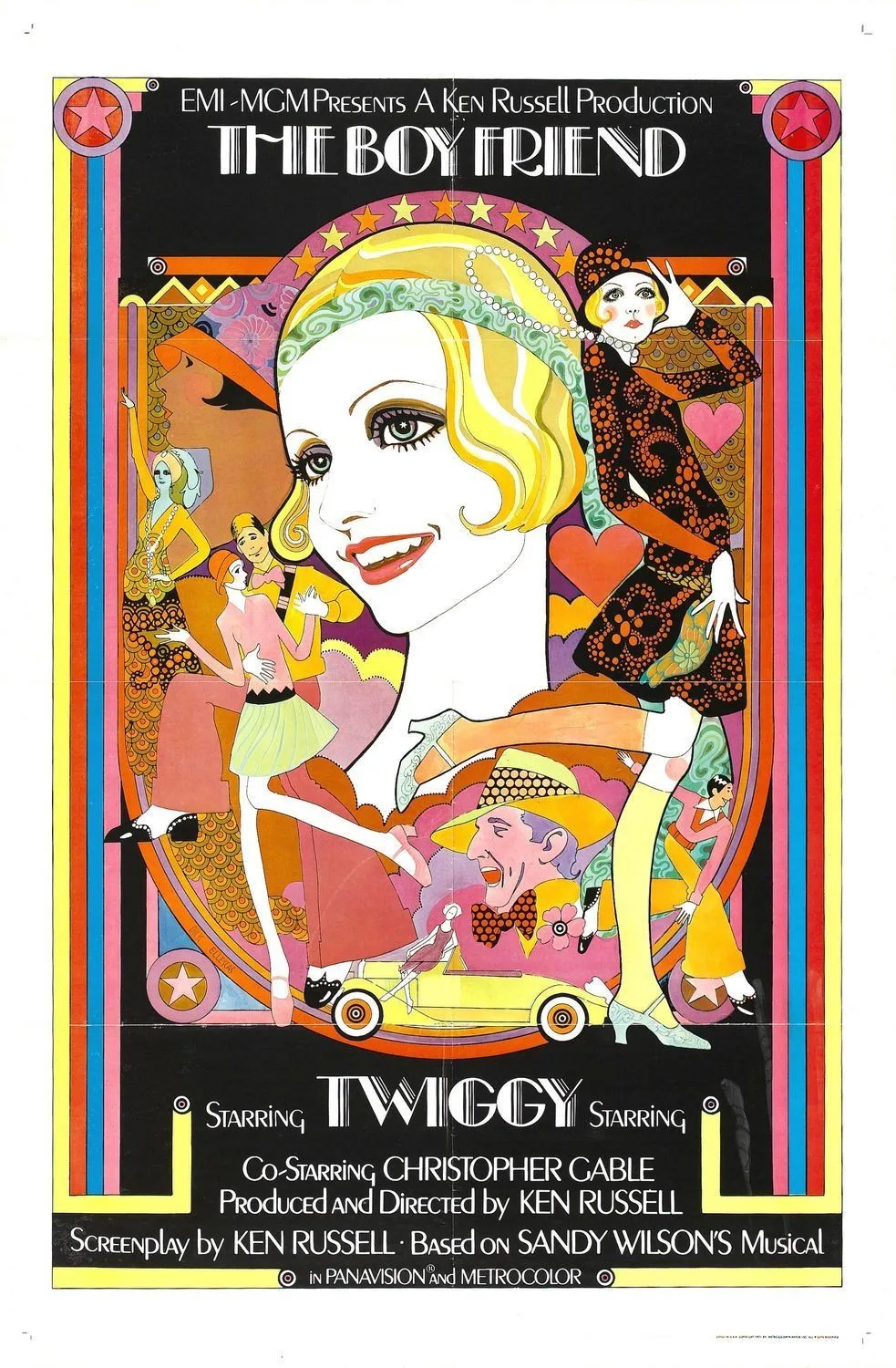

All this helps us put a finger on the fundamental visual poverty of Ken Russell’s “The Boy Friend.” His musical is supposed to be a spoof on Berkeley-type 1930s musicals, of course, but after a while we realize that Russell belongs on Berkeley’s side. Even when he’s not deliberately doing Berkeley takeoffs, his camera is so joyless that it undermines every scene.

The idea is that a big Hollywood director is in a box at the edge of the stage, and everybody in the musical hopes to be hired for the movies. Russell allows this idea to dictate his camera placement; there are endless point-of-view shots from stage to box, and from box to stage, until we feel clobbered by them. His other three camera angles are (1) from the back of the stage looking out, (2) a full-front of the stage, and (3) the classic cliche shot showing the action from backstage.

These five camera angles almost literally dominate the visuals. Russell doesn’t seem to be having any fun. He doesn’t want to draw out the magic of the wonderful Sandy Wilson songs, or the inner life of his performers. As usual, he reveals himself as a woman-hater. It is bad enough that Glenda Jackson (who is in most of his movies) needs the attention of a good dentist; must Russell constantly attack her with a sadistic makeup artist?

Twiggy, the star of the show, emerges relatively undamaged. She is so passive, so wide-eyed, so innocent, so much a nothing, that Russell can’t really get at her (the way he can with the sharp-edged Miss Jackson). Twiggy sings adequately and dances adequately, and she’s so . . . cute. She’s a pale little puppy, and a lot of the women in the audience seem to treasure her as they would a Hummel figurine titled “Malnutrition.”