Run, Jason, run. The Bourne films have taken chases beyond a storytelling technique and made them into the story. Jason Bourne’s search for the secret of his identity doesn’t involve me in pulsating empathy for his dilemma, but as a MacGuffin, it’s a doozy. Some guy finds himself with a fake identity, wants to know who he really is and spends three movies finding out at breakneck speed. And if the ending of “The Bourne Ultimatum” means anything at all, he may need another movie to clear up the loose ends.

That said, so what? If I don’t care what Jason Bourne’s real name is, and believe me, I sincerely do not, then I enjoy the movies simply for what they are: skillful exercises in high-tech effects and stunt work, stringing together one preposterous chase after another, in a collection of world cities with Jason apparently piling up frequent-flier miles between them.

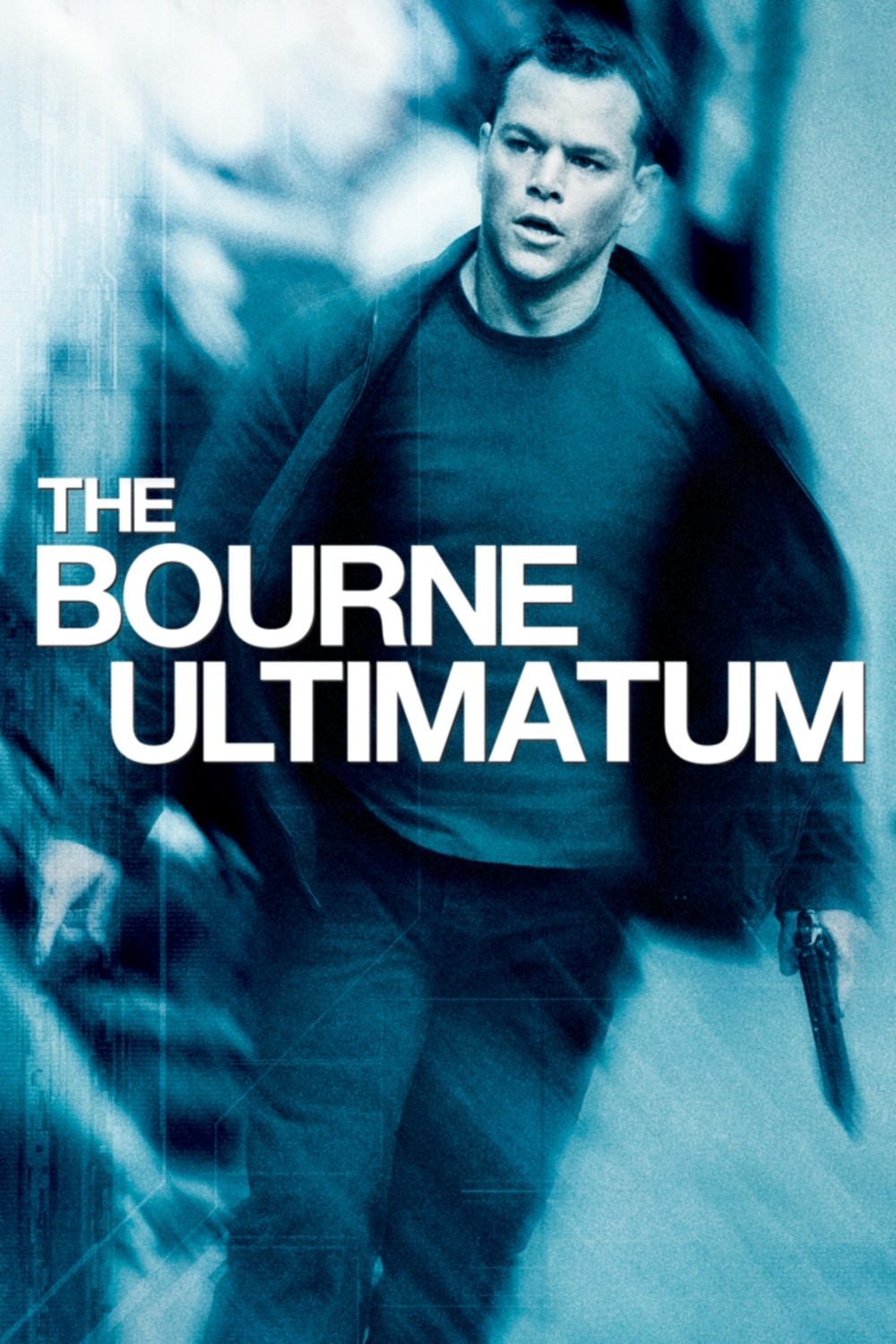

“Ultimatum” is a tribute to Bourne’s determination, his driving skills, his intelligence in out-thinking his masters and especially his good luck. No real person would be able to survive what happens to him in this movie, for the obvious reason that they would have been killed very early in “The Bourne Identity” (2002) and never have survived to make “The Bourne Supremacy” (2004). That Matt Damon can make this character more convincing than the Road Runner is a tribute to his talent and dedication. It’s not often you find a character you care about even if you don’t believe he could exist.

This time, Bourne is engaged in a desperate hunt through, alphabetically, London, Madrid, Moscow, New York, Paris, Tangier and Turin, while secret CIA operatives in America track him using a perplexing array of high-tech gadgets and techniques. I know Google claims it will soon be able to see the wax in your ear, but how does the CIA pinpoint Bourne so precisely and yet fail again and again and again to actually nab him? You’d think he was bin Laden.

And why do they want him so urgently? Yes, he is proof that the CIA runs a murderous secret extra-legal black-ops branch that violates laws here and abroad, but the response to that is: D’oh! The CIA operation, previously called Treadstone, is now called Blackbriar. That’ll cover their tracks. It’s like if you wanted to conceal a Ford plant, you’d call it Maytag. Seeking a hidden meaning in the names, I looked up Treadstone on Wiktionary.com and found it is a “fictional top-secret program of the Central Intelligence Agency in the Jason Bourne book and movie series.” Looking up “Blackbriar,” I found nothing. So they are hidden again from the Wik empire.

In his desperate run to find the people who are chasing him, Jason hooks up in Madrid with the CIA’s Nicky Parsons (Julia Stiles), who is given several dozen words to say with somber gravity before Jason is off to Algiers and running through windows and living rooms in the Casbah; I think I recognized some of the same steep streets from “Pepe Le Moko,” which is a movie about just staying in the Casbah and hiding there, a strategy by which Jason could have avoided a lot of property damage.

Of course there are sensational car chases, improbable leaps over high places, clever double reverses and lightning decisions. Sometimes we cut back to CIA headquarters (although surely a secret CIA black-op would not be hidden in its own headquarters) and meet agent Pamela Lundy (Joan Allen), who suspects maybe there is something to be said on Jason’s behalf, and her boss Noah Vosen (David Strathairn), who must have inherited hatred of Bourne as part of the agency’s institutional legacy, since he wasn’t in the first two movies. And then finally that shadowy nightmare figure in Bourne’s flashbacks comes into focus and, in the time-honored tradition of the Talking Killer, explains everything instead of whacking him right then and there. After which there is another chase.

The director, masterminding formidable effects and stunt teams, is Paul Greengrass (“United 93,” “The Bourne Supremacy”), and he not only creates (or seems to create) amazingly long takes but does it without calling attention to them. Whether they actually are unbroken stretches of film or are spliced together by invisible wipes, what counts is that they present such mind-blowing action that I forgot to keep track.

There are two kinds of long takes: (1) the kind you’re supposed to notice, as in Scorsese’s “GoodFellas,” when the mobster enters the restaurant, and (2) the kind you don’t notice, because the action makes them invisible. Both have their purpose: Scorsese wanted to show how the world unfolded before his hero, and Greengrass wants to show the action without interruption to reinforce the illusion it is all actually happening. Most other long takes are just showing off.

But why, if I liked the movie so much, am I going on like this? Because the movie is complete as itself. You sit there, and the action assaults you, and using words to re-create it would be futile. What actually happens to Jason Bourne is essentially immaterial. What matters is that something must happen, so he can run away from it or toward it. Which leads us back to the MacGuffin theory.