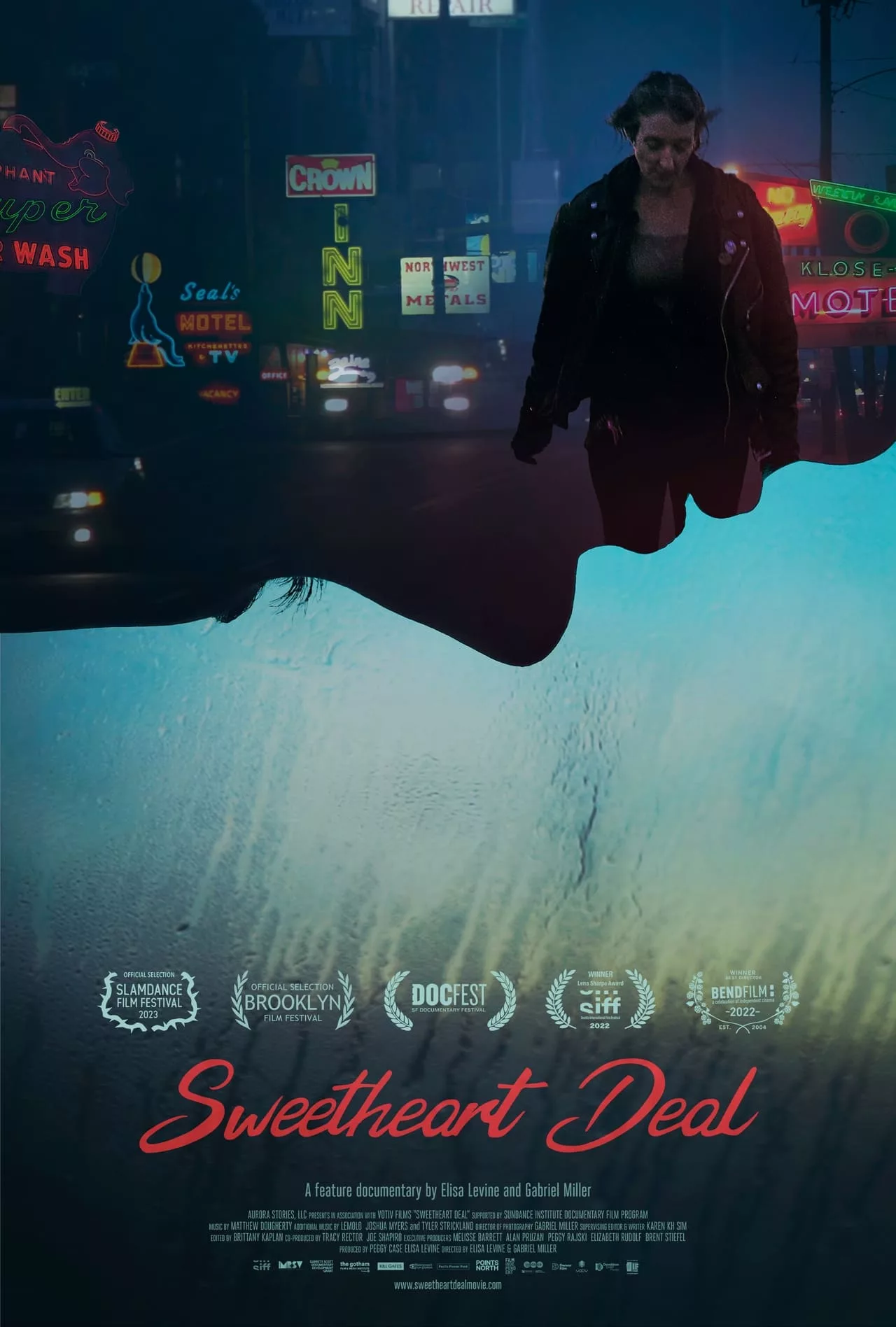

Seattle is one of the largest and most populous cities in America. It’s a center of technology, culture, and industry, and its massive port opens it up to the world. But in “Sweetheart Deal,” a new documentary by Elisa Levine and the late Gabriel Miller, all of Seattle is narrowed down to one wide strip of road – Aurora Avenue – lined with cheap motels, fast food, and tire retailers. The rest of Seattle, in all its diversity and plenty, doesn’t exist at all on Aurora (except for the fact that Seattle’s economy powers Aurora as well). On Aurora, women work the strip, negotiating prices with drivers peering out of expensive cars. This is all captured by Levine and Miller with unflinching clarity.

It took years for Levine and Miller to make the film. They found four “subjects” – Kristine, Krista, Tammy, Sara – all of whom are prostitutes, all of whom are addicted to heroin. They “turn tricks” (their words) to feed the addiction. “Vicious” doesn’t even come close to describing the cycle. It’s obvious Levine and Miller had to establish trust with people to allow themselves to be “seen” in this way and thus embedded themselves in the world of Aurora Avenue. An obvious precedent was set by Mary Ellen Mark, whose groundbreaking “Streetwise” (the book and the documentary) showed the life of Seattle street kids. These abandoned feral runaway children clearly trusted Mark to an almost shocking degree, and a film like “Streetwise” – or “Sweetheart Deal”- is as much about the filmmaker as it is about the subject. How on Earth did Levine and Miller get these women to trust them so deeply?

One of the “gateways” to Aurora Avenue is a character who calls himself “The Mayor of Aurora.” This is Laughn Doescher (aka “Elliott”), first seen feeding pigeons outside his RV, parked on Aurora Avenue. Elliott knows everyone on the street. He opens up his RV to women who need to come in from out of the cold, have a nap, eat some food. These women rely on Elliott for shelter, and he provides them with a peaceful respite with (seemingly) no strings attached.

The stories of the four women profiled are diverse but also distressingly similar. Tammy’s parents are devastated at what she is doing, and yet they beg her for money to pay for cigarettes. They depend on her “wages”. Kristina was a welder, and she loved it, but her addiction made it impossible to stay employed. She says the only thing that makes “prostitution tolerable” is heroin. She’s a feisty personality. Krista (street name “Amy”) is from a middle-class home, and her smiling sorority pictures don’t tell the whole story. She resorted to sex work to feed the addiction. Amy occasionally goes home to clean out under the care of her mother (many of the women no longer have a home to go to), but heroin has its claws in her. Sarah lost custody of her children. She keeps trying to get off drugs, so she can get her kids back, but the “dopesickness” is debilitating. Watching her negotiating with a “john” in a bleak motel room is depressing and infuriating. This woman should be in a hospital.

Elliott’s intersections with these women grow in complexity as the film progresses. They trust him. He helps them. Tammy, though, has the clarity of mind to keep her distance. She’s friends with Elliott but on her terms. She’s tough and street smart. Amy isn’t street smart at all.

“Sweetheart Deal” was filmed over a period of about ten years. Many events happened in those years, one of which made national headlines. These new revelations appear about an hour into the film, and everything seen up until that point must be re-evaluated. The audience goes through the same process the women go through. The curtain is pulled back. There are many documentaries where real-life events swerve unpredictably, outside the original project’s scope, films like Gimme Shelter, Capturing The Friedmans, or Daughter From Danang. “Sweetheart Deal” shares much in common with these films. Watching it is like being trapped in a nightmare and finally wrenching yourself awake. The truth is almost too horrible to bear when it comes out, but it’s better than living in a lie.

Gabriel Miller’s cinematography is moody, poetic, and mournful. The shadows and rain-wet sidewalks blur into neon, which then gives way to trashy fluorescent lighting, evoking Aurora’s gaudy, bleak atmosphere. The footage of these four women is so intimate. They allow us into their lives, to see them at their worst. The film is handled so sensitively that it never feels exploitative.

Sherlock Holmes comes up a couple of times as a reference point. Elliott has a fondness for the character, comparing himself to Sherlock at one point. There’s a scene where a dopesick Sarah lies in the back of the RV, and Elliott pops in a “Sherlock” DVD for her to watch. It takes gifted filmmakers to weave those random references, gathered over ten years, into a motif or at least a potential theme. Sherlock Holmes famously solved his crimes through a process of inference, using information visible to the naked eye and putting together clues based on what is already blindingly obvious. “Sweetheart Deal” operates in the same way.

With “Sweetheart Deal,” a detective’s magnifying glass isn’t necessary. The clues are there from the start, hiding in plain sight. “Sweetheart Deal” doesn’t pull its punches. The life depicted is too tormenting to put a positive spin on it. But, in the same way “Tiny” emerged as the “star” of “Streetwise” (so much so that people are still haunted by her 40 years later), Kristina, Krista, Tammy, and Sarah take on such three-dimensional weight once you’ve met them, you won’t ever forget them.