Emmet Ray is like a man with a very large dog on a leash. The dog is his talent, and it drags him where it wants to go. There are times in “Sweet and Lowdown” when Ray, “the second-best jazz guitarist in the world,” seems almost like a bystander as his fingers and his instinct create heavenly jazz. When the music stops, he’s helpless: He doesn’t have a clue when it comes to personal relationships, he has little idea how the world works, and the only way he can recognize true love is by losing it.

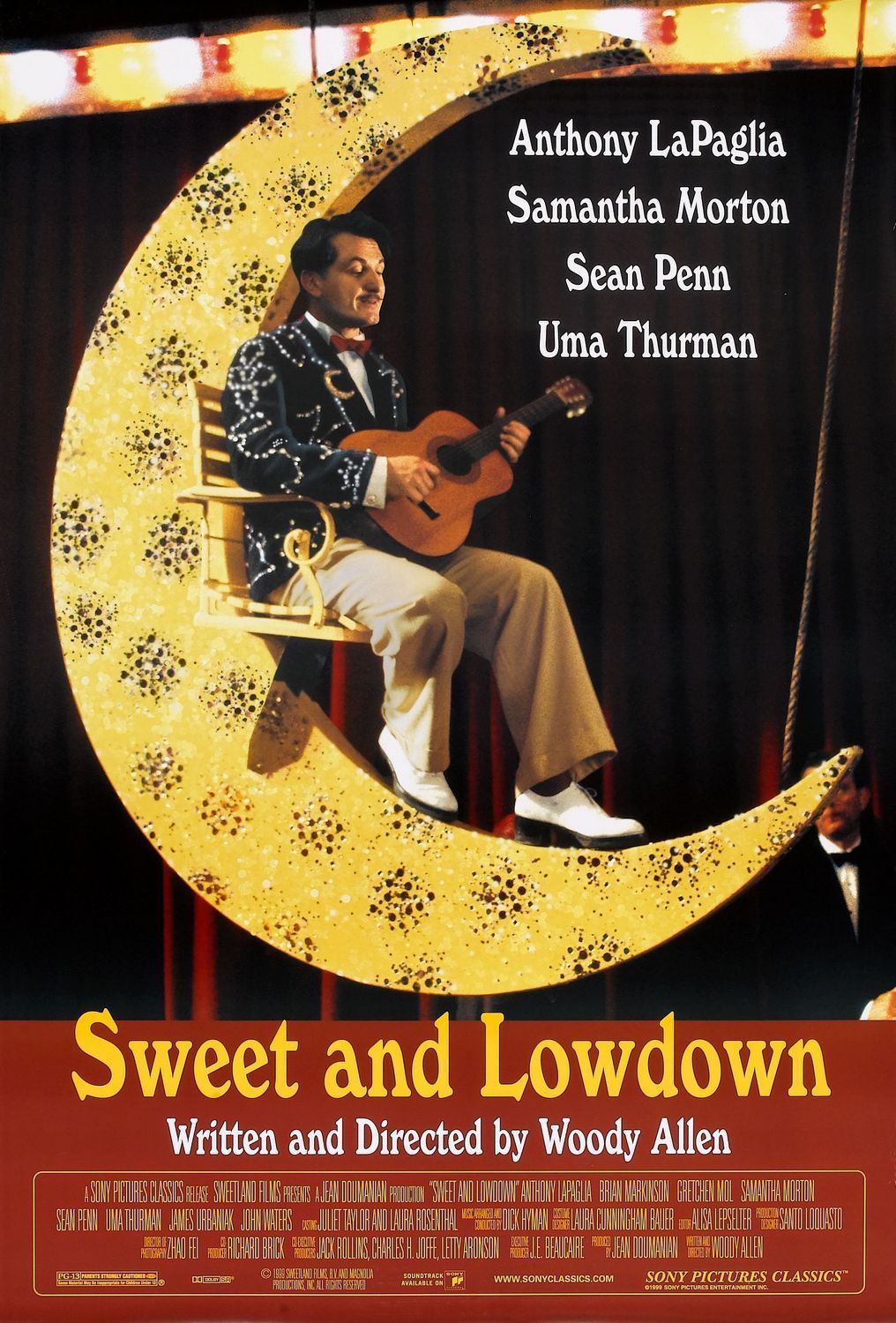

Emmet Ray is a fictional character, but so convincing in Woody Allen’s “Sweet and Lowdown” that he seems like a real chapter of jazz history we somehow overlooked. Sean Penn, whose performances are master classes in the art of character development, makes him into an exasperating misfit whose sins are all forgiven once he begins to play. With his goofy little mustache and a wardrobe that seems patterned on second-hand guesses about what a gypsy jazzman in Paris might wear, Emmet Ray looks like a square peg lacking even the round hole.

Here is a man, who, when we first meet him, is already considered peerless among American jazz guitarists, yet is running a string of hookers as a sideline. Who drinks so much that only sheer good luck spares him, night after night, from getting himself killed. Who is forgiven by his colleagues, most of the time, because when he plays, there is magic happening right there on the stage.

Here is a man so lonely that he doesn’t even know the concept. “Your feelings are locked away so deeply, you don’t even know where to find them,” he’s told. He’s wounded: “You say that like it’s a bad thing.” One day on the boardwalk at Atlantic City, he meets the woman who would be the love of his life, if he were sufficiently self-aware to understand that. Her name is Hattie (Samantha Morton), and she is a mute, although Emmet is so self-absorbed that it takes him quite a while to realize she never says anything.

Morton plays Hattie like one of the great silent film heroines. Before dialogue, before the Method, before sound, actors were hired because they embodied roles. You could be a carpenter or a secretary one day and be pushed before the camera on the next. Mabel Normand’s “The Extra Girl” (1923) tells such a story. Morton is an accomplished British actress, but here she is not used as an actress so much as a presence, as in the silent days, with eyes that drink in Emmet, a body that yearns toward him, and a heart that’s a pool of unconditional love and admiration. Her love is all the more remarkable because she can hear, which allows her not only to understand his music, but to endure his inept and often crude stabs at conversation.

Emmet, of course, is too unhinged to understand what a treasure she is. You don’t know what you’ve got, till it’s gone. Vain, with an inferiority complex, a pushover for flattery, he is swept away by a society floozy named Blanche (Uma Thurman), who catches him stealing a knickknack at a party. She doesn’t care; she’s a little fascinated that a man she believes to be a genius would still harbor the instincts of a petty thief. “You have genuine crudeness,” she tells him, as if she were saying he had nice eyes.

“Sweet and Lowdown” is structured by Allen as a docudrama; we hear Allen’s own voice explaining passages in Ray’s life, and we see jazz experts like Nat Hentoff, who comment on aspects of Ray’s career. Jazz history often seems constructed out of barroom stories improved upon over the years, and Emmet Ray’s life unfolds like lovingly polished anecdotes; there are even alternate endings to some of the legendary episodes.

Looming over everything is Ray’s awe of Django Reinhardt, the Gypsy jazz guitarist who ruled the Hot Club of Paris from the 1930s to the 1950s; despite having lost fingers in a childhood accident, he played the guitar as nobody has before or since. Again and again, Ray ruefully observes that he is indeed the best–except for that Gypsy in France. A moment when he finally encounters Django provides one of the movie’s best laughs.

The guitar playing in the movie is actually by Howard Alden. You will want to own the soundtrack. Alden taught Sean Penn to play the guitar, in lessons so successful that Allen’s camera never has to cheat: We hear Emmet Ray and we see Emmet Ray’s fingers, and there is never reason to doubt that Penn is actually playing the guitar.

Emmet Ray is the least Woody-like character I can remember at the center of an Allen movie. He embodies Allen’s love of jazz, but few of his other famous characteristics, save perhaps for attracting worshipful women. Much has been made in some psychobabble reviews of the fact that Hattie is mute, as if that represents Allen’s ideal woman; perhaps it’s inevitable that a director whose films have been so autobiographical would attract speculation like that, but Allen’s real-life partners, from Louise Lasser through Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow to the Soon-Yi Previn seen in the 1998 documentary “Wild Man Blues,” have all been assertive and verbal. I think Hattie is seen as Emmet’s ideal woman, not Woody’s, and it’s interesting that Allen, who has gradually stopped casting himself as the lead in his films, now seems happy to make the leads into characters other than versions of himself.

I have made Emmet Ray sound like a doofus and a cold, emotional monster, and those are elements in his character, but “Sweet and Lowdown” doesn’t leave it at that. There is also a sweetness and innocence in the character, and his eyes warm when he’s playing. You sense that this is a man who was equipped by life with few of the skills and insights needed for happiness, and that music transports him to a place he otherwise can hardly remember. If Emmet Ray’s talent is indeed like a large dog, pulling him around, then I am reminded of a pet cemetery marker in Errol Morris’ “Gates of Heaven,” which reads: “I knew love. I knew this dog.”