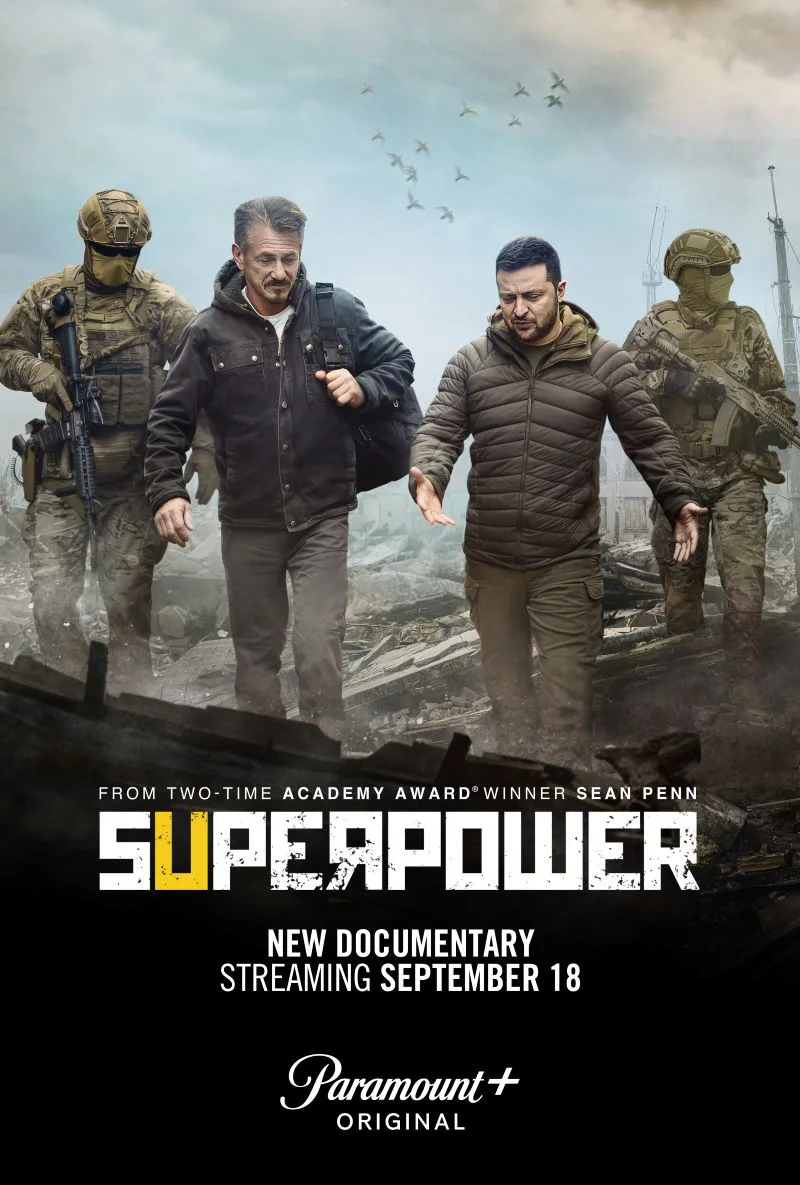

There have already been so many powerful and illuminating nonfiction projects about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (including “20 Days in Mariupol,” possibly one of the greatest war documentaries ever made) that any filmmaker attempting their own entry needs to bring their A-game, especially if they’re not from Ukraine. When this chapter of history is closed, and the storytelling about it is evaluated, “Superpower” will be a curious footnote.

The movie’s co-director, narrator, and onscreen guide, Sean Penn, can’t decide what kind of movie he wants to make. So we get a generalized portrait of what happened during the last 15 or so years; a sensitive, picaresque work of battlefield reportage, using material gathered during Penn’s seven trips to Ukraine; a sardonic, self-critical but necessarily navel-gazing meditation on celebrityhood and politics; and an analysis of the way Volodymyr Zelensky, the president of Ukraine, used his own celebrity to win the office, essentially treating voters like audience members, figuring out what values they wanted to see incarnated by a president, then writing the role for himself and playing the hell out of it.

That last film is by far the most interesting of the ones that Penn gives us in this grab-bag of a movie. And it’s a shame because the few relatively brief sections of “Superpower” that scrutinize Zelensky as a self-created political icon (in the tradition of Ronald Reagan, Fred Dalton Thompson, and Donald Trump) are the most authoritative and fascinating by far.

Penn, an experienced actor, writer/director, and a troubled person whose violence made him a tabloid fixture, understands performance at every stage of the creative process. He also understands the media’s tendency to latch onto a catchy narrative and milk it, and many more things that non-famous people might only get theoretically. “Superpower” is at its best when letting Penn and co-director Aaron Kaufman put Penn’s spoken observations over clips pulled from early in Zelensky’s career, including talk and news show appearances, pieces of a presidential debate, and some innovative campaign ads and other material that play like pieces of a scripted television series or film by an auteur actor-director whose persona is so carefully crafted that he can afford to try out filmmaking experiments. (Zelensky even stages dynamic “walk and talks” like in a Hollywood movie, something that nobody can do well unless they’ve committed the lines to memory.)

Penn quotes Ronald Reagan and points out Zelensky’s use of comedy and music to engage viewers/voters. These parts of the movie are sharp enough that one wishes the entire project had concentrated on the idea of Zelensky as, essentially, an actor who wrote himself a scrappy underdog character who represented his own best fantasy of himself, played it so well that he won the presidency, then found himself having to play two more roles on top of it, wartime leader and national emblem, and nailed both.

There’s a far less interesting shadow equivalent of the “Zelensky playing Zelensky” movie happening as well, in which Penn attempts to explain his obsession with traveling into danger zones, using his fame and money to get into places where ordinary people couldn’t. Among other hotspots, he went into New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina and Haiti following the 2011 earthquake. Penn certainly had serendipity on his side: he had scheduled an interview with Zelensky that just happened to fall on the day before the invasion, and Zelensky kept it, and gave him more time on the actual day of the invasion as well. (Zelensky understands the value of using celebrity to carry a message as much as Penn does.)

There’s a moment near the end where Penn and his crew are in a danger zone, and we see Penn hiding a small knife on himself and mock-threatening the camera with his fists; one supposes it’s supposed to be self-deprecating. But it falls flat for all sorts of reasons. Penn says he’s constantly being asked why he keeps making a Hollywood version of Batman or an intrepid journalist in a war epic. He says people ask him, “Who do you think you are, Walter Cronkite?” But he offers no compelling answer to such questions, instead brushing them off as less important than the story he’s using his celebrity to help tell.

This only makes us wonder why he didn’t avoid the mechanics of his own presentation entirely rather than make us watch as he barely wrestles with it while embracing cliches he’s been accused of embodying. As in Oliver Stone’s political documentaries, but with less erudition, Penn surrounds himself with experts—including diplomats, reporters, Ukrainian soldiers and citizens, and even men who are implied to have been James Bond-level spies—but doesn’t cede the floor, instead cutting back to himself listening with a respectful or grave expression. (There’s already been a full-length documentary about this aspect of his life, “Citizen Penn,” which was made by a director not named Sean Penn and shows the conflicting aspects of his personality with much more insight.)

The backbone of the movie is a compact tour of recent Ukraine history. It’s adequately presented, at the level of a nightly newscast segment. The best bits concern the dioxin poisoning of President Victor Yushchenko by Russian assets and some citizens’ pre-invasion worries that Zelensky was too soft and compromised (by Russian friendships and money) to be a good president during anxious times. But it’s nothing you can’t learn from reading articles online. The final section evolves into hero worship, which seems forgivable when applied to a genuinely heroic person.

This isn’t a bad film by any means: it does a creditable job of convincing us that Penn’s heart is in the right place (as an activist) even when the execution is sometimes impulsive or clumsy. But it lacks focus.

On Paramount+ now.